by Anna Roos van Wijngaarden // July 18, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Wilderness.

For centuries, pigments were derived from organic sources but, with the Industrial Revolution, these ancient techniques faded in the light of more efficient, predictable machinery. Today, there is not much nature left in the process of textile dyeing, and the predominantly synthetic setup now accounts for 53 percent of the fashion industry’s emissions and tons of water use. The antidote is a more sustainable natural dyeing revival that seeks to reconnect natural methods with aesthetic pleasure. Among this group of pioneering bio-designers is Ilfa Siebenhaar, who makes up half of the Netherlands-based Living Colour Collective, with Laura Luchtman.

Siebenhaar describes her experimental way of dyeing as co-creation between human and organism. According to the textile artist, the process is more intuitive for those who grew up in nature, which has a way of expressing its richness if one allows it to take its course. Her own admiration for the imperfections found in wilderness took root during her childhood, when she would often immerse herself in her grandfather’s tropical greenhouse. Pursuing a fashion design degree with a focus on bio-design at the Willem de Koning Academy in Rotterdam was a logical progression. Today, Siebenhaar works in her lab in Amsterdam, exploring the potential of organic dyes and bacterial pigments for a sustainable textile industry—and, naturally, art for art’s sake. When you let living organisms to do their work spontaneously, the results tend to take on artistic expressions. We spoke to Siebenhaar about the implications of collaborating with nature, and how the wild elements she engages seep into the final product.

Ilfa Siebenhaar, portrait // Courtesy of the artist

Anna Roos van Wijngaarden: People often label the kind of organic creations you make as “slow.” Why do you think that is?

Ilfa Siebenhaar: I think it has to do with the fact that you’re looking more at a process. Whether I work with natural dyes from flowers or with bacteria, it takes quite a bit of time, so you respect it more instead of wanting to turn it into something that has to be done very quickly. Moreover, as you go through those necessary growth phases, stillness arises. That is why slow fashion is often cited as a countermovement to fast fashion, which depletes the earth by ignoring natural processes.

Ilfa Siebenhaar and Laura Luchtman: ‘CYMATICS RESEARCH,’ 2016-17 // Courtesy of the Living Colour Collective

ARW: Your techniques engage living organisms but also have an element of control and, in that sense, are ultimately human-made. To what extent do your experiments leave space for the wild elements of nature to do their work?

IS: It depends on the technique. If you grow the bacteria directly on the textile using the “live-dye” technique, you have some level of control. You apply samples of the bacteria to the textile on which it multiplies. So, you can assume that something will arise in those places, but you never quite know how those bacteria will eventually choose their own path. I see the process on its own as a form of wilderness. I merely release the bacteria on the textile, and it starts creating an organic pattern depending on where it can obtain optimal nutrition. For example, the textiles are never completely flat, so you get bumps, which they find comfortable to sit on, since the temperature can be just a bit more favourable. Some bacteria do not colour well in the process, so it stays lighter in those areas. But it depends on many other factors. In the end, we humans approach the result mainly aesthetically: the bacterium has created a beautiful pattern.

I see wilderness very much as something that moves freely. Nature finds its way everywhere. You see this, for example, when all kinds of plants grow over old ruins. That’s also what happens with bacterial dyeing on a small scale. But, at some point, you have to stop that growth too, because otherwise the colour will be affected.

Courtesy of Ilfa Siebenhaar and the Living Colour Collective

ARW: You’ve created commercial bacterial dyes for Puma. How do you see this collaboration as an intervention into the world of fast-fashion?

IS: We had a very pleasant collaboration in which there was room for an approach to textile dyeing with bacteria, a new technology not yet on the market. We looked at its opportunities instead of focusing on “problems” such as fading colours. I find it difficult that everything must be an exact copy of something else in the current industry. Why don’t we start a clothing collection as a “white canvas,” dye them with colours that fade over time, on which we repeat the process with another colour of natural dye? It would be just like the cycles in nature. And the unique layering that emerges in the garment really belongs to you.

The industry doesn’t think that way yet, but I think there will be a transition in that direction. Artificial synthetic dyes are less affected by UV light than bacterial dyes. But, again, is fading necessarily bad? I think we need to learn to accept that dye doesn’t have to last 50 years and that we can also look at it with a design-based approach. With denim, for example, it is already fully accepted that jeans fade, and we find that it actually becomes more beautiful as a result. We give it more meaning and begin to cherish it, because it grows with us as a living piece.

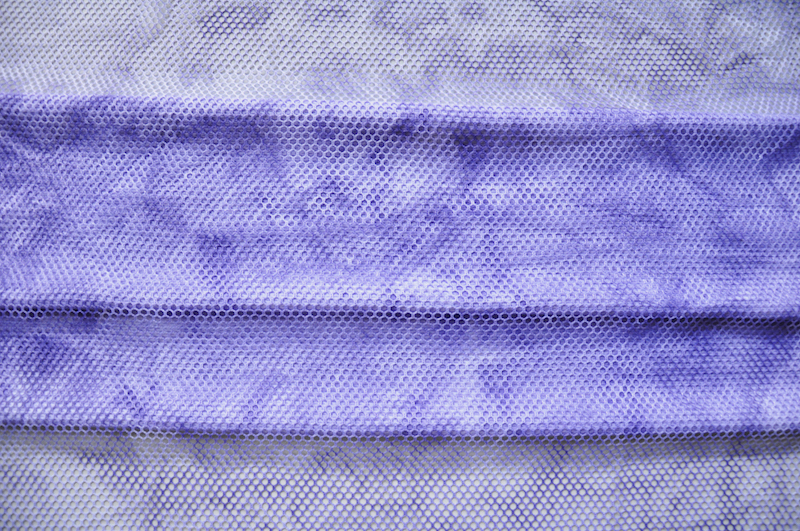

Textile mesh // Courtesy of Ilfa Siebenhaar and the Living Colour Collective

Ilfa Siebenhaar and Laura Luchtman: PUMA x Living Colour Collective: Design to Fade, 2020 // Photo by Ingo Foertsch

ARW: How would that look in practice?

IS: Perhaps we should make it easier to change the colour of a fabric that fades. It would align nicely with the seasons. You could work with light colours in the spring and put brighter layers on top in the summer, when there is a lot of light, which would fade that tone again. By autumn, you might re-dye it with some deeper colours. What if we came up with this kind of model that is working with nature? Perhaps, people could eventually even dye [their clothing] themselves. I think there are still many opportunities for us as artists and designers to teach the industry and the consumer: about how we look at dyes, what kind of impact they have and how we can change the way we think about them.

Peace Silks // Courtesy of Ilfa Siebenhaar and the Living Colour Collective

ARW: Besides bacteria, you’re also dyeing with organic waste. These resources are literally left to decompose in nature at the end of their life. Can you elaborate on your latest project and what you’re hoping to find out?

IS: I am currently mapping out residual flows from the Dutch flower industry: for example, from flower float parades and the tulip industry, and I turn it into a tangible product such as a blouse. The technique I use for this is called “bundle dye.” You spread the organic ingredients over the textile, bind it tightly and subject it to steam exposure. When you roll out the package, you’re left with a beautiful imprint of—in this case—the petals. The process can, once again, be controlled, but you can never fully predict how the result will come out. This is how I see myself as a designer: I like to play with coincidences and processes where you can partly steer and partly also have to trust the process and leave it to chance.

Zooming in on my experiments with the tulip, in the first phase in which they are grown, all the heads of the flowers come off. I did all kinds of tests with them and got some very nice dye extraction of the coloured leaves. Later in the process, the tulips are pulled out of the ground and the peels are removed. I also experimented with that outer edge and got similar exciting results. I find working with residual flows interesting, because you discover what you can do with all those different parts. It’s literally wild, what you’re working with. And even though organic waste will eventually go back into the cycle anyway, it is interesting to see if you can give it renewed value first.

Courtesy of Ilfa Siebenhaar and the Living Colour Collective

ARW: You are already using your art to solve sustainability problems today. Do you believe there is still a lot to be gained there?

IS: Nature is my greatest source of inspiration. I am convinced that all the answers to our contemporary self-created problems around waste and environmental pollution can be found in nature. The question is how we, as humans, should use this knowledge. Biodesign through future design thinking methods and biomimicry are very good examples of this. They help us to come up with innovations that help us move forward instead of further exploiting and polluting the earth. They allow us to work as an ecosystem, just like nature. We are part of nature and should perhaps place ourselves less outside it. I also believe that this will bring us more in touch with ourselves, so that we feel more connected to the world around us and feel more respect towards it.

Textile dying is a very interesting way to work with sustainability. There are billions of bacteria in this world and the fact that we don’t know half of them yet makes my heart jump. There is something big that we don’t know yet and I am eager to discover it step by step. In a way, my experiments are also about discovering this wild unknown.