by Adela Lovric // Aug. 15, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Wilderness.

Through her multidisciplinary practice, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg explores a wide array of topics—artificial intelligence, synthetic biology and evolution, to name a few—while probing the complex relationships between humans, nature and technology. This past June, the London-based artist won the S+T+ARTS Grand Prize – Artistic Exploration for her experimental interspecies living artwork ‘Pollinator Pathmaker,’ which is currently active in Cornwall, London and Berlin. Originally commissioned by Cornwall’s Eden Project in 2020, it aimed to draw attention to the vulnerability of insects vital for flower pollination and reproduction.

For this expansive project, Ginsberg initially began to research what an artwork for pollinators would look like and delved into how they experience the world. Seeing landscapes through their eyes prompted deeper considerations about empathy and humanity’s role in environmental destruction and preservation. Rather than envisioning a garden for people, she asked: what would we see if pollinators designed it? Opting to create an artwork for them, she proposed an algorithmic solution to a planting design that would serve the greatest diversity of pollinator species possible. The pandemic-induced lockdown spurred the creation of a dedicated website, pollinator.art, which opened up access to the algorithm for public use. Anyone can use it to generate personalised gardens by adjusting parameters like size, location, soil type, light exposure, amount of plants and the intricacy of the planting pattern.

The debut edition blossomed in 2021 at Eden Project, followed by a new one last summer at the Serpentine in London. Now in Berlin, Ginsberg’s first international edition of the ‘Pollinator Pathmaker’ commissioned by LAS Art Foundation is presented in the front courtyard of the Museum für Naturkunde. It boasts over 7,000 plants spanning 80 varieties providing food and nesting spots to a wide variety of insects. Starting with this central garden and encouraging people to plant their own algorithmically-assisted iterations in private and communal spaces, Ginsberg’s ambition is to make the world’s largest climate-positive artwork and to challenge what we think of as art.

Just as it started to bloom, the artist spoke to us about this artistic project that will keep developing in Berlin over the next three years. We discussed the role of technology in her nature-oriented artwork and what she as an artist and her audience as potential collaborators can do for the environment and regeneration of its processes and pathways.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker LAS Edition,’ 2023, planting in the forecourt of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin // Commissioned by the LAS Art Foundation, photo by Frank Sperling

Adela Lovric: How is this Berlin edition of the ‘Pollinator Pathmaker’ different from the earlier two in Cornwall and London?

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: To start, the plant list is different. There are a lot of plants that do cross over with different climatic conditions, but we also worked with the museum and local experts here to bring in species that are very particular to this climate of hotter summers and colder winters, that would survive and also suit local pollinators. The algorithm generates a new planting scheme every time you run it, so we chose something here that was very different from what’s in London and in Cornwall. Each edition is different, depending on the location and the conditions. The Cornwall one is very stripy and the Serpentine one drifts across 11 different beds. Here, we’ve gone for something that is super bold, crazy tall plants like artichokes and angelica mixed with shorter ones, and really challenging this very formal space of the forecourts of the Museum für Naturkunde. While we may find it beautiful because we’ve transformed this forecourt from very tired-looking grass to this abundant carpet of flowers, it won’t look like a conventional garden since it is actually not for us. With each new commission, especially in a new region, the idea is to create a new plant list that is then put back on the website so that more people in the region can plant. It’s a generous act.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker,’ 2023, installation view of LAS Edition at Museum für Naturkunde Berlin // Commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, photo by Juan Camillo

AL: What were the responses to the first two editions of the ‘Pollinator Pathmaker?’

ADG: It’s been really well received, even though it challenges a lot of different audiences. One of my favourite reviews of it so far came from a gardening journal in the UK called The Hardy Plant Journal, which is the journal of the perennial society, people who are very into the kinds of plants used here. The editor came to inspect both the artwork at Eden Project and the one at the Serpentine and wrote what I thought was a very positive review. One of his comments was that the problem is that they might be too beautiful and were against the ethos of the artwork. It was really exciting for me that the gardening community could actually see the humour in it, but also the point of it. Here in Berlin, LAS Art Foundation had the ability to really push this DIY campaign for the first time, getting schools and private individuals involved. I’m hoping, also because of this particular location, that this broader response from outside the art world gets picked up and people plant their editions. I think Berlin has a very special community and a really interesting set of ways that green spaces operate in the urban environment here.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker,’ 2023, installation view of LAS Edition at Museum für Naturkunde Berlin // Commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, photo by Juan Camillo

AL: What is the design logic behind the ‘Pollinator Pathmaker?’ Is there any aesthetic input from you in the process of generating garden schemes?

ADG: I’m actually trying to use the technology to stop me from getting involved, but we generated many schemes and you can’t help but interfere and try and choose your favourite one. The algorithm is actually arranging things on multiple different scales; there’s the big field vision of general patterns, and then the track lines for insects that memorise the locations of the plants, and then random patches. So there is a logic behind it, and you can play with the algorithm to tune how bold the pattern is as well. When you create your own edition, there’s a way that you can prefer a certain aesthetic and interfere in the process. But with each DIY edition, you get a unique number and you can revisit it online. And if you don’t like what you generate, you can just create a new one.

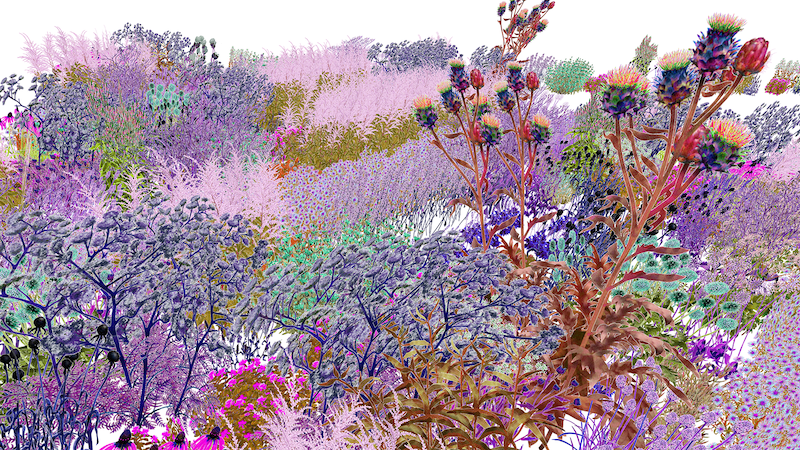

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker LAS Edition,’ 2023, digital render, pollinator vision // © Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

AL: Why are, in your opinion, art and technology good and important conduits for healing nature and for healing our relationship with the parts of nature outside ourselves?

ADG: As an artist, I’m also using technology to critique it. I don’t think technology can solve the problems we have with the natural world, the way we exploit and destroy it. Rather, these solutions are social and political. So the idea behind ‘Pollinator Pathmaker’ is not to create a solution for the pollinator crisis. It’s really to engender a feeling of agency, but also to actually make us focus on nature as an artwork. The technology itself may actually create better support for diverse ecosystems. We’re doing scientific research both in the UK and here with the museum, looking at whether this kind of planting does actually create a more diverse ecosystem. But technology is not the solution. This is also presented as a way to ask questions of technology—why do we make them, who do we make them for and who gets to decide these questions? It’s a gently political exploration and critique.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker LAS Edition,’ 2023, opening in the forecourt of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin // Commissioned by the LAS Art Foundation, photo by Dario J. Lagana

AL: What could be the downsides of involving technology in a project like this?

ADG: There is this question of it being seen as a solution, which is always problematic—that by creating something like this, we feel like we’ve solved a problem. But the benefit here outweighs those particular risks because what it’s actually doing is empowering people to plant. My partner is horrified at what I’ve planted at home because it’s grown to be two-and-a-half meters tall. I’m not a gardener, so I would never have been brave enough to choose those plants, to know how to arrange them, and the pleasure I’ve got from learning to look after them is enormous. The technology is just a tool to actually make us spend time caring for nature.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker LAS Edition,’ 2023, opening in the forecourt of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin // Commissioned by the LAS Art Foundation, photo by Dario J. Lagana

AL: What can art and its worlds and systems learn from this artwork and more generally, the processes of rewilding, ecological repair and interspecies work?

ADG: This is not a natural ecosystem planted outside, there are plants from all over the world. With the expert group, we chose not to focus on native plants only because they are locally appropriate so they’re not invasive. So that’s the first thing—it’s an artificial landscape designed for nature, so it’s a very different way of creating an ecosystem. The other big challenge to the art world that I’m proposing is creating a climate-positive artwork. I also show in museums and I use digital media and that’s all very carbon-consuming. Here, we actually have an artwork fabricated in plants. It has its own climate impact because of the soil we’re moving, the plastic pots, the shipping of plants, but it’s here for at least three years, so it starts to outweigh that negative. There’s also a question of how we measure that, and that’s something I’m really interested in.

The other thing that’s really important to me is upending the idea of value. The art market is all about the one, the singular, the limited edition. This is an unlimited edition. The idea is: the more people who have one, the better each one is because each one supports the other. For me, that’s a strong statement to make to commissioners and when I’m trying to get more partners involved. It’s a very different way of thinking about how we create art and what its purpose is. For me, this is about playfulness, joy and celebrating nature. I call it an artwork and not a garden project because I think situating it in that context makes a powerful statement in itself.

Exhibition Info

LAS Art Foundation

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg: ‘Pollinator Pathmaker’

Exhibition: June 20, 2023–Nov. 1, 2026

las-art.foundation

Museum für Naturkunde, Invalidenstraße 43, 10115 Berlin, click here for map