by Aoife Donnellan // Sept. 12, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Privacy.

Through animation, painting, drawing and sculpture, British artist Emma Talbot’s practice explores the inner landscapes of private thoughts. As part of Berlin Art Week, Talbot has developed a site-specific installation of works to be showcased at KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art’s Kesselhaus space. Paintings on silk, sculptural works and hanging objects evoke mythical voices of sirens, furies, witches and spirits warning audiences of impending ecological and political events. ‘In the End, the Beginning’ imagines viable alternative futures for society.

Talbot’s considered practice interrogates the relationship between personal experiences and their social origins using a dialogue between drawings, paintings and 3D objects. As her faceless characters investigate their surroundings, moving through shared emotional and physical landscapes, the figures consider the dissolution between emotions, space and narrative. Her work illustrates the benefits of building communal internal and external worlds to secure a sustainable shared future.

‘In the End, the Beginning’ opens at KINDL, alongside the group show ‘POLY. A Fluid Show,’ which also features Talbot’s work, among others. We spoke to the artist about how she conceives of her characters as a neutral vehicle, through which private existential questions can become fictionalized.

Emma Talbot, installation view, Kunsthall Stavanger, Norway // Courtesy of the artist and Kunsthall Stavanger

Aoife Donnellan: Is there a natural beginning when you’re conceiving new work?

Emma Talbot: Usually, it starts with a period of making drawings. Drawing happens in a very open way, I don’t predetermine what I’m going to draw. I try to download the images from my mind. I don’t decide what a subject for the work will be.

By making these drawings, I start to see that there’s a preoccupation, a kind of concern. I fill in that [concern] with a lot of research, a lot of reading and online research, so that I can build a very nonlinear narrative. Then, it depends whether I think this should be a painting, or a three-dimensional work, or an animation. It is really dependent on where it might be shown, what kind of space I’m thinking about, or what I can do with different ways of making.

AD: What motivates that moment of translation, from the interior and the individual, to an external and shared feeling?

ET: I think the important thing for me is that the private—this internal narrative, or voice, say your own private thoughts—is always bound up in something that’s much more shared, much more universal. We are thinking beings in the world, so those things aren’t separate. We’re all experiencing these very personal, emotive thoughts and feelings at the same time as we’re trying to inform ourselves. We’re connecting to a bigger picture of the world.

The work is an exploration, but I really wanted it to be like how human consciousness operates. We’re in these big systems, but we think that we have very individual thoughts and experiences. Yet one of the most amazing things we benefit from doing is sharing thoughts and experiences. We actually really get a lot from that, as humans.

Emma Talbot, installation view at Arsenale // Courtesy of the artist, copyright LaBiennale di Venezia

AD: Your latest work for KINDL, ‘In the End, the Beginning’, will be shown in the Kesselhaus. Did the scale of the space inform the piece?

ET: When they first invited me, I looked at images of the space and I was really excited about it. It’s a really interesting space. To think of my work in that space, [I wanted] to draw something out of the space, other kinds of readings.

One of the things about the silk work is that it includes text and image, and it’s really light material. So even if it’s a really big scale, it’s not heavily monumental. It has this quality of being present in the space, but not being overbearing. In the silk work, there are quite a lot of thoughts describing a network of thinking, verbally or visually.

Emma Talbot: ‘The Age L’Età,’ installation view at Collezione Maramotti // Courtesy of the artist and Collezione Maramotti

AD: When you do include text in the work, how do you go about writing the text or finding the text? How does research interact with your practice?

ET: One of the things that the work does is allow me to investigate that which preoccupies me. If I looked over my work, I would see how, over time, my interest in various things has changed. The thing that preoccupies me the most tends to be something that quite a lot of us are really preoccupied by, so it tracks time a little bit. It makes sense of me wanting to understand things I don’t fully know. A lot of research is about trying to gather information and understand things for myself.

It used to be that I used quotes from different places, but now the text is all my own writing. It isn’t an illustration with a text that serves one another, but a proposal of an idea. I think of the text a bit like speaking, because speaking is immediate. It’s interesting for me because I have this visual structure, but then I also have to think: what do I really need to say? What is verbalised within this?

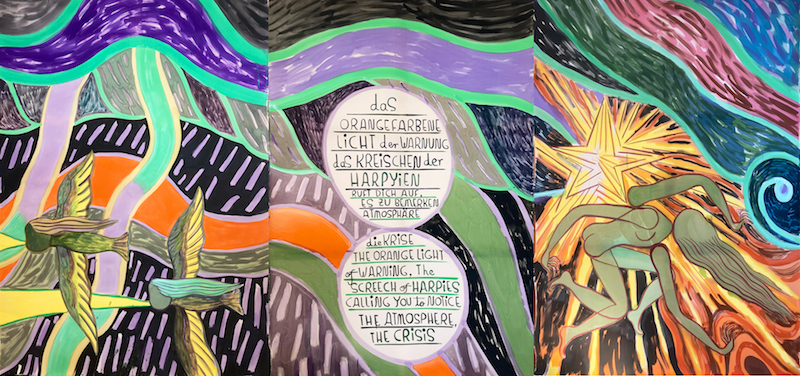

Emma Talbot: ‘The Storm’ (details for Kindl exhibition) // Courtesy of the artist

AD: The characters that appear in your work are generally faceless. Does this further the interrogation between private and shared experiences?

ET: Yeah, it’s interesting that the character, if you like, is me. I think of it as me from the inside. I don’t know what I look like from the outside, we can’t see our own faces, so it became this faceless figure.

It was really useful because it started to become a universal figure, like an avatar or a vehicle. It’s a figure that can be a human present in this situation, or exploring, searching around. That’s mostly what they’re doing: climbing about and flying around, trying to investigate something. It became really important to me that this isn’t a particular person. This is almost a neutral vehicle, even though I know it’s me. It moves us through space and it doesn’t have those sorts of characteristics. They might become more of a fiction.

Emma Talbot: ‘The Age/L’Età,’ installation view at Whitechapel Gallery // Courtesy of the artist, photo by Damian Griffiths

AD: Your KINDL work evokes myths and legends, have you always been interested in historical storytelling?

ET: Probably yes, because myths are ways of explaining and understanding. Metaphors are really useful because they help us to step outside of something and understand it in a quite abstracted, fictional way. There have always been myths, humans have always made myths and stories, and they provide a creative backdrop to human life.

I noticed in mythology that a lot of the figures that warned others were female, like sirens or different kinds of figures who called out or warned people that they were about to die. We’re in a situation where it feels like that’s what you can hear, all these sorts of warning signs. You get a sense of this disaster that we’re facing. I imagined that all of these mythical figures would be coming back, basically screaming at us. That’s the way I wanted to use it, to anchor it in the contemporary.

Emma Talbot, installation view at Arsenale // Courtesy of the artist, copyright LaBiennale di Venezia

AD: Your work also appears in a group show at KINDL, ‘POLY. A Fluid Show’. How is it working in a group show with themes around mixing, queering and hustling as ways of dissolving boundaries, especially when this theme of universality or identity dissolution is so central to your work?

ET: The work that I’m showing in the group show, ‘When Screens Break,’ is an animation and some silk hangings. They describe the way that we got seduced by devices. The way devices, like our phones, operate is that they’re almost like a confidant, something that pays a lot of attention to us, because we get these alerts, and rewards from using our devices, which are designed around human behaviour.

My idea was that we were seduced into being reliant on devices, and then there comes a point at which we’re totally networked, like you can’t even make a doctor’s appointment without having some device. I made the soundtrack for the animation, which is quite dreamlike. It’s a sci-fi proposal, if you like, but it’s not impossible. That could be our situation.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

KINDL – Center for Contemporary Art

Emma Talbot: ‘In the End, the Beginning’

Exhibition: Sept. 17, 2023–May 26, 2024

Opening Reception: Sunday, Sept. 16; 6–9pm

kindl-berlin.com

Am Sudhaus 3, 12053 Berlin, click here for map