by William Kherbek // Sept. 26, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Privacy.

Diamond Stingily’s art regularly treads the uneven ground between interiors and exteriors. Her recent exhibition at Isabella Bortolozzi, ‘I’m Not Coming Back Here,’ centred on the home of Stingily’s grandmother and mother, which was sold after the passing of her mother. The spaces featured in the images are intrinsically private, but their meanings expand, entering the interiorities of viewers as they pass among them, and quite literally through them. In a number of works in the show, Stingily overlays monochrome reproductions of these richly personal spaces on mirrors, and suddenly the viewer and the spaces are transfigured: they become dialogues across times, minds and histories.

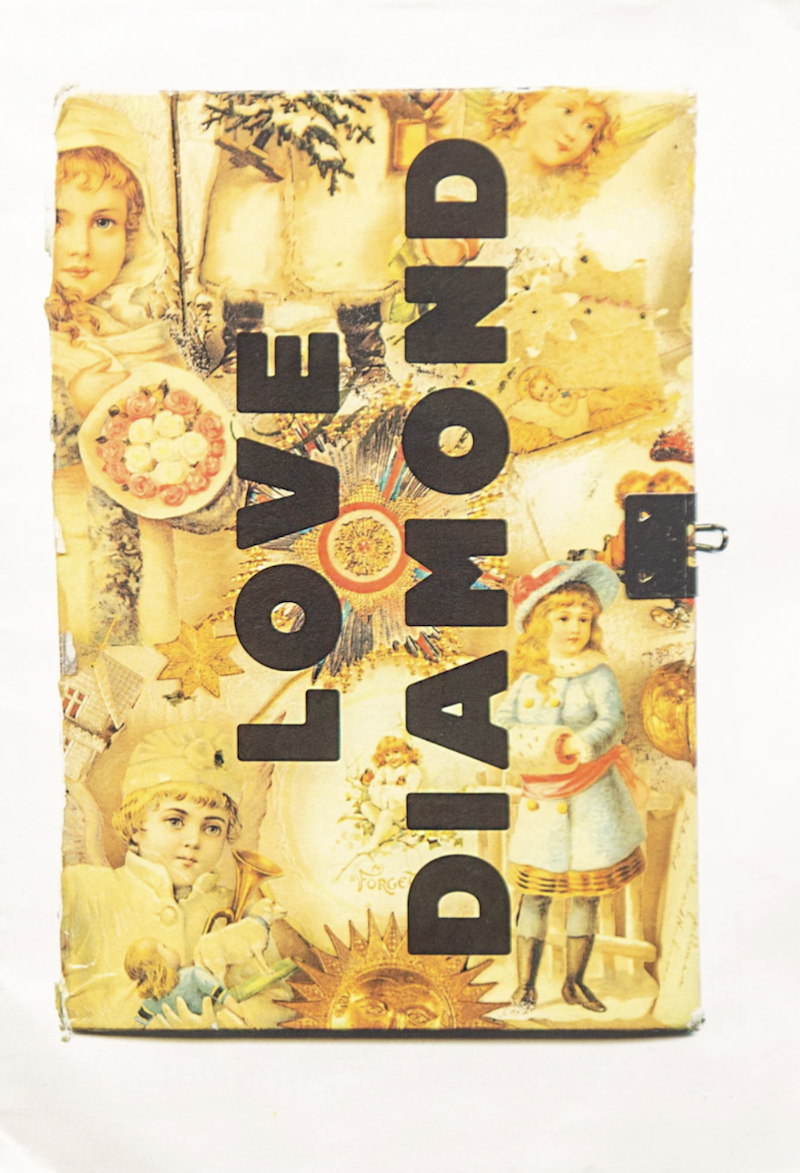

Stingily’s capacity to generate narrative power by foregrounding thresholds between interior, ostensibly private, spaces and public space also features in her work ‘Entryways’ (2021), a series of doors supported by baseball bats—a signifier of self-reliance and institutional neglect to Americans familiar with the experience of what the economist Manfred Max-Neef called the “under-developing” areas of the country. Some of Stingily’s most powerful explorations of the boundaries between what is private and what is public have not been objects, but textual or dialogic works. With the help of the endlessly innovative American artist Martine Syms, Stingily published entries from her childhood diary under the title ‘Love Diamond’ (2013), and has even conducted interviews in her podcast ‘Sparkle Nation Radio’ (with help from the poet Gabrielle Rucker and the multidisciplinary artist Precious Okoyomon), featured on Montez Radio. Stingily spoke to us about these and other works, which explore the nature, performance and frequent repositioning of what is and is not considered private.

Diamond Stingily: ‘I’m Not Coming Back Here,’ 2023, installation view // Courtesy of Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

William Kherbek: In your works involving mirrors at Bortolozzi, you draw viewers into the spaces depicted in the works. Was this element of bringing external people into ostensibly private spaces something that you planned with the work or an aspect that emerged?

Diamond Stingily: I didn’t really think about people coming into the spaces, or how I would feel emotionally, until I saw [them] taking selfies in the spaces. At times, I thought it was amusing and, at other times, I was sensitive to it. Being an artist on social media, I’m able to be tagged in things I wouldn’t necessarily [ordinarily] see. I didn’t really think about people coming into the spaces, because it was different at the opening for me, just trying to look past myself and still see the image. But I think every time I talk about the pieces, I have a different perspective.

The work started from a journal entry, and then my family having to sell the home my mom and my grandmother lived in, because they’re dead. I was thinking of these very personal spaces and how they’re no longer personal after a while—memory, and other people’s interpretations of a memory, versus what I think, or what I thought. I was thinking a lot about personal memory versus collective memory. There was also a lot of grief involved in the images I chose, and I think my work has a sense of vulnerability to it. I was open at that time, maybe still now, to being vulnerable sharing.

Diamond Stingily: ‘Entryways,’ 2019, installation view, ‘Wall Sits,’ Kunstverein München, Munich, 2019 // Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

WK: In a work like ‘Entryways,’ there’s also a strong sense of vulnerability. Doors, which in theory are a boundary between the inside and outside, are seen to be substantially less secure than they might otherwise be. The baseball bat is also an object with multiple codings—in one case leisure, in another personal security. They speak of a sense of precariousness. Could you take us into the origin and ideas behind this work?

DS: A lot of the things I make are things I wish to see in institutions, museums and galleries. I think maybe that’s one of the reasons why my work is well received, because it’s genuine and I’m not making it hoping that it fills up the space and makes people comfortable. I think the viewer is highly intelligent and can use their imagination with the work. I like imagination and play a lot, and I try to include that in my work, where you see something and you can imagine where it was, or where it should be, or why you think it’s here. [You can imagine] a whole entire story behind it.

Diamond Stingily: ‘In the Middle but in the Corner of 176th Place,’ 2019, installation view, ‘Wall Sits,’ Kunstverein München, Munich, 2019 // Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

WK: This personal element you mention also seems to be an undercurrent in ‘Trophies for Trying,’ and that work in particular seems to touch on a distinction between personal or private victories and more public achievements. Could you talk about how you think about the work, in particular how these inscriptions—recognising victories that would often otherwise be invisible or entirely private—question notions of what a true achievement might be?

DS: When I was making that piece I was being optimistic but also nihilistic; thinking things matter, but they don’t matter, and the contrast of that. There’s this duality of being a person, having personal achievements, which we know are so much different from what a public achievement could be [seen as]. Worrying about public achievements can drive someone crazy. I think personal achievements can be a lot more heartfelt. I made that piece thinking about athletes, mainly high school athletes, people who have been scouted or talked about since they were in elementary school, and how a lot of people have high hopes because of that. The work was very American, in that way. I was thinking about people from the midwest, and people from the south. There’s such a huge emphasis on sports growing up, there’s more emphasis on being good at a sport than being good academically. I was thinking a lot about people who probably thought, or were told that, they would be professional athletes and then they were never able to achieve that. But within their lives, they’ve had a lot more personal achievements than public achievements, and that it’s still ok. Or maybe it’s not ok. I was thinking about that contrast and what it means.

Diamond Stingily: ‘Doing the Best I Can,’ installation view, CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco, 2019 // Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

WK: With ‘Love Diamond,’ you published possibly the most private thing a person can: a childhood diary. Could you speak about that work and how you became interested in publishing it? And how has it felt for you making something so private essentially available to anyone? Was it a challenge for you?

DS: I actually really enjoyed it. I don’t mind it at all. At that age, I was so silly. I was a funny kid. I was very smart, so when people approach me and say “that journal entry was very funny,” or “you really just wanted to be respected [in a situation],” I’m like: you see me! And it’s nice to be seen. I was very unfiltered as a little girl, as well, so I think a lot of my entries are funny because it’s just me being honest, because I didn’t know I’d be publishing it 20-something years down the line.

There’s one entry in particular where I’m thinking about a movie, and I say “I don’t understand this movie, so I’m going to watch it again.” I’m still like that. It’s really cool when people can also see themselves within something that you created [for yourself]. It’s a little different now. I don’t know if I would publish a high school journal, or a journal that I have now, but I think 8- or 9-year-old Diamond, she was such a ham, low key. She liked attention, even though she swore she didn’t! She would love it. She would feel really good.

Diamond Stingily: ‘Love Diamond,’ 2013, Dominica Publishing, Los Angeles // Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

WK: Being here interviewing you, I can’t help but ask about your own history as an interviewer on your podcast works. How did you find the process of interviewing? Was it easy to get people to open up to you and speak about more private things?

DS: I had two shows, ‘The Diamond Stingily Show’ on NoWave and I had a show with the poet and artist Precious Okoyomon and the poet Gabrielle Rucker, ‘Sparkle Nation Radio’ on Montez Press Radio. They were both similar, but different. ‘Sparkle Nation’ had more interviews, while ‘The Diamond Stingily Show’ was just me having people pre-record their writing, and writing they were interested in. I’m good at getting people to do things they wouldn’t normally do. I’m really good at talking people into doing stuff, especially if it’s with me. Even if they are going to do it alone, I make it seem like I’ll be right there the whole time.

I had a lot of fun with ‘The Diamond Stingily Show’ because I liked what people were sending me. People are so strange, and I really enjoy that strangeness. I just wanted people to share their ideas, or their poems, or their essays, or what writers they’re interested in. I wanted to spark conversation. This phrase is overused, but it was very communal for me, doing those shows.

WK: You mentioned your social media profile earlier. Social media has changed our notions of privacy perhaps more than any other technology. Do you have a sense of how it has affected your understanding of what is public and what is private?

DS: I’ve definitely calmed down on my social media presence. I mainly post things about my work, my career, but every once in a while I do get weird online, and I’ll post some weird stuff like a poem, or something like that. I’ve been told that I’m still weird, which I guess I good. I don’t take it as an insult. I was at a residency for six months and one of the artists said she knew me because she follows me on social media, and she said “You can be so weird!” I thought I was past that! But, I’m still there. That made me laugh so hard. Some of the things I post are a bit silly, very niche humour.

WK: Humour and really any creative act on the internet is so vulnerable to the loss of legibility and context people like danah boyd speak about. How are you thinking about that legibility loss given that your works are often so contextually rich?

DS: Honestly, I don’t think I can answer that right now because I’m in it. We’re in motion right now, and maybe I won’t have an answer to a question like that until I’m in old age.

WK: We’ll schedule another interview in 30 years.

DS: Yeah, hit me up when I’m old! I won’t know the answer until I’m out of the storm, and we’re so in it right now.

Artist Info

bortolozzi.com/diamond-stingily

greenenaftaligallery.com/diamond-stingily