by Cristina Ramos // Oct. 27, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Privacy.

Lewis Hammond is a Berlin-based, British artist who depicts a small and highly symbolic world in his paintings, reduced to hideaways where bodies surrender to one another and indulge in an obfuscated, ambivalent intimacy. There is a fine line between existential dread and human comfort in this ambivalence, which seems symptomatic of the current situation in which we find ourselves. Private space is built from a mixture of fictional plot and experience, resulting in highly charged and Tenebrist images.

In Hammond’s works, the sense of intimacy is not only restricted to being with another body, but also comes from the vulnerability of the characters themselves, as they seem to pine for connection beyond their own skin. Life is set apart from what is public, and space belongs to oneself, whether as the characters in the paintings or the ones who are looking at them. We spoke to Hammond about how he develops these deep and rich interior worlds within his paintings.

Lewis Hammond: ‘Turbulent Drift,’ 2022, installation view at Arcadia Missa, London // Photo by Josef Konczak, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London

Cristina Ramos: In the painting ‘I have my thoughts… they are mine’ (2023), the duality between outer presence and inner existence is depicted in the doubling of the image, as if the smooth section on the right side of the painting would give life to the blurred world of ideas expressed on the left-hand side. What’s the idea behind building up this difference?

Lewis Hammond: I was interested in developing an almost impenetrable sense of interiority in the child in the painting. He is being held in a protective embrace that attempts to resist the gaze. He seems to possess autonomy and a defiant selfhood from the safety of his cocoon.

The repeated image in its rawness reads like a glitch, a memory or a moment in a sequence of images. His expression is subtly shifted toward a different kind of melancholia… I see an emotional fatigue. It’s important for me to explore the multitudes of emotions we experience, I am trying to make sense of the world that I inhabit.

The dissonance of these two styles of painting in this work taps into the feeling of a shifting mental state, an innately human experience that also allows a different entry point into the painting, one where we can see ourselves in the child we are looking at, the rawness is the chink in the armour. I wanted to make a painting that centred vulnerability in a quieter way… not through enacted violence, trauma or via other social cues, such as class and race.

Lewis Hammond: ‘I have my thoughts.. they’re mine,’ 2023, oil on copper, 60 x 40 cm // Photo by Fred Dott, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London

CR: Dreams reflect the most inner, private spaces, but also bring the most certain imaginative space. They provide a refuge for visions, which appear to be transposed somewhere else like a poem or a painting, as in ‘untitled (study for a shrine)’ (2022). It’s a temporal place where things can be stretched beyond their material or sensorial qualities. What is your relation with the oneiric? Do you draw from it?

LH: Daydreaming and letting the mind wander is of more significance for me. It’s in the shower where I probably form the most definitive images for works. They appear quite fully formed in my mind’s eye and then I take this memory to the studio and attempt a kind of reverse engineering to locate that fleeting picture.

When describing a dream, we often find that language falters. I come up against a similar struggle when making a picture using my memory. But I also think this is when the most interesting things happen. It is the intention to locate and approximate toward the mind’s eye where the odd slippage and ambiguity of my collated imagery schism and uncover something else. In its best moments, it feels like an uninterrupted channelling of my unconscious.

Outside of art making, the importance of dreaming/imagining our world in a different way is also of great importance to me. I mentally wander those projected futures often as it re-instils my hope for the present.

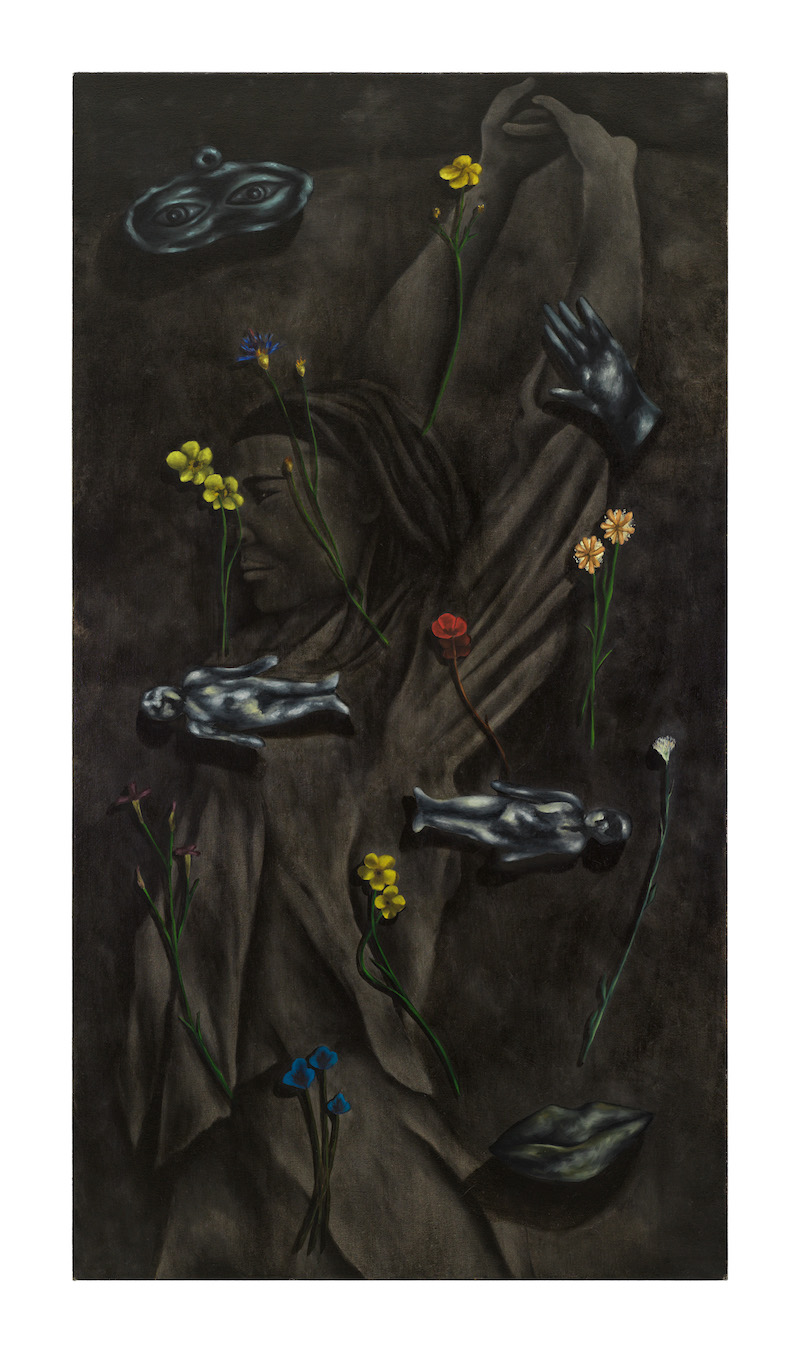

Lewis Hammond: ‘untitled (study for a shrine),’ 2022, oil on canvas, 130 x 70.5 cm // Photo by Josef Konczak, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London

CR: A very striking aspect of your practice is how you depict feelings that are not usually shared in public space; such as mourning, loss or explicit desire (thinking here of ‘fountain’ (2023) ). Your paintings hold space for these feelings to be free, to be released. In this way, do you see them as depicting the overlooked?

LH: I don’t think I see them as overlooked as such. We are peppered with hyper-sexualised images via advertising, social media etc. Through the news ticker we also ingest more images of trauma / violence / catastrophe than what we can reasonably process. But these images do not feel like something we can share in – the news reel has a bludgeoning effect and the sexualised ads are lessons in aspiration and consumption.

I want my paintings to land closer to home… however improbable they may appear, they relate to the messiness of life and I think that can be felt when looking at them. I am often disappointed with the photographic reproductions of paintings as I think my work in particular communes better in the real, which is perhaps a hindrance and is at odds with a lot of work being made in this “age of content”, but then again I welcome that it works better offline, almost in opposition to the excess of unprocessable digital imagery we are bombarded with.

Lewis Hammond: ‘fountain,’ 2023, oil on canvas, 40 × 50 × 2.5 cm // Photo by Joerg Lohse, courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York

CR: When building up private space—whether painting a physical structure or a psychological one—I wonder what is the painting process like for you? Do you depart from a fixed place, be that an image or a feeling you’d like to capture? Or do you rather let the painting’s skin develop its own language?

LH: Unfortunately, for better or worse, I do not have a fixed methodology when developing a work. There is usually a period of image gestation, drawing, collaging and generally playing around with compositional elements to arrive at a preparatory image that I can reference to begin the actual painting. The preparatory image usually demands the scale the painting should be. There is also a simple question of how big do I want the things I am depicting to be! The emotive register of a work guides me in this decision making.

Depicted intimacy, violence, desire… can behave in quite strange ways. So there is also a consideration for how I want the work to affect the viewer. So much of how we engage in art is determined by the structures outside of the work itself, I am often simultaneously referencing our political present and an art historical past. It is fundamental for me that these other contexts are a part of my making process. As much as I have autonomy over the images I create, they still appear with pre-existing baggage. So, although I think about what emotion I am trying to capture and/or illicit, the process is also a navigation of my personal response to the way in which we visually understand the world.