by William Kherbek // Mar. 5, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Grief.

Pan Daijing’s solo exhibition ‘Mute’ opens this week at Munich’s Haus der Kunst. Featured prominently in the exhibition is an excerpt from the video work ‘Grief Lessons’ (2021-2023). The work combines elements of choreography, performance, sound and narrative in an elegiac exploration of the ways in which grief is enacted, performed, subsumed and elided. The work is shown on small and large screens distributed across several rooms in the Haus der Kunst, and its component images provide a nonlinear exploration of the workings of grief and other emotions. In the piece, different feelings blend with each other, and inscribe themselves on the bodies of performers.

The experience of grief is, in many ways, the experience of experience itself in the increasingly unstable reality of the present, in which war and climate change—and wars brought on by climate change—consume greater and greater geographical territory on the planet. Living in this moment, for the artist, is not merely an occasion to grieve however, and indeed, grief is not in itself a simple emotion, as the ensuing conversation about ‘Grief Lessons’ and the wider exhibition indicates.

Pan Daijing: ‘Tissues,’ 2019, performance view, Tate Modern, London // Courtesy of the artist

William Kherbek: Could you take us into the origins of ‘Grief Lessons’ as a work?

Pan Daijing: The title refers to a work I showed in Graz last year. It came from an hour-long film I never showed publicly. This film was extracted from footage collected over the years, especially from exhibitions. It’s very similar to the way I deal with moving image work more generally, and to how I compose music.

I would take the encounters from exhibitions, or shoot a scene (I’m not biased against making things happen “for the camera”) but in this case I recorded things with a loose idea and directed more by intuition. [It was the] same with the audio material, it was recorded over time. It was an exercise centred around a sense of movement in relation to the space, and about a sense of movement in dialogue with the stillness of the space, searching for a familiarity in unfamiliar psychological spaces.

In what’s being shown, I think there’s a sense of ambiguity, a looking for direction, searching, searching for connections, searching for the unknown and the violence that runs inward at the moment of despair. It doesn’t so much land on a feeling of grief, specifically, but ‘Grief Lessons’ as a metaphor holds this work together. There’s a feeling of constant transit, as if we’re going somewhere, and not knowing where. There’s a sense of urgency, but not of rushing, and that brings an uncanny sense, a potential for loss, which interacts with the moment when the images synchronise. What is being shown reflects a search for a sense of hope.

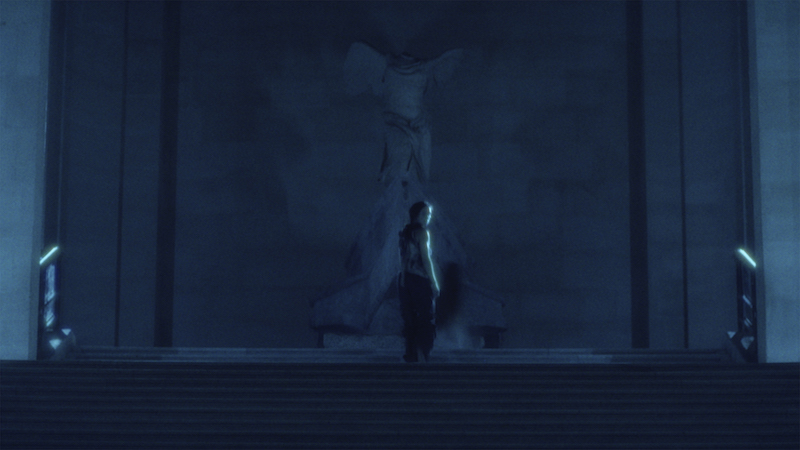

Pan Daijing: ‘Grief Lessons,’ 2023, installation view, Grazer Kunstverein // Courtesy of the artist

WK: So would you say the work touches on a sense of “anticipatory grief,” meaning something like an awareness that losses are coming and the question of how to prepare or manage such future losses or absence?

PD: I do feel like you’re talking about a “not being able to.” That’s an observation I share about the time we’re in now. There are so many difficulties, we have to engage and connect with the things that sit close to us: our own emotions, our own needs, our connection to the world we live in every day. From my upbringing, this feeling was apparent every single day, and I see, since I moved abroad in recent years, that this is universal, a kind of dilemma we’re confronting daily. The time [we’re in] now may not be worse than ten years ago, but every [stretch of time] has its own colour, and this colour, for me, is something that is not still. It’s in constant motion, and I’m just trying to convey this disconnection or the feeling of not being able to perceive something in a specific way, or offering a sense that maybe there’s not a single way to look at something.

WK: In speaking about universality and individual perception, how do you approach the experience of translating such a deeply personalised set of sensations and perceptions in ways that will be interpreted to a wider audience, many of whom may have very different backgrounds?

PD: I definitely advocate for every individual, every upbringing, every background being unique in its own way. Even a person carrying their history may not have full access to the information it offers. We all know when I say the word “hurt” or the word “love” it means something different for everybody, but at the same time there’s a shared connection to that feeling that brings a sense of community, not a community centred around certain backgrounds or education, but things that come down to a very human level. This is something I’m very curious about, and that possibility brings me hope when I’m examining, or observing, through my work, how different individuals connect to the work, or connect to themselves and eventually to each other through the work. For me, that’s something that’s very exciting.

Pan Daijing: ‘Avalanche,’ 2022 – 2023, film still, Louvre, Paris // Courtesy of the artist

WK: Have some of these responses, these connections created, stayed with you after the making of works?

PD: Absolutely. I consider this part of my research, because it’s offering or inviting people to open up to something that might put them in a vulnerable space. For example, my sense of care comes from a place of dialogue; it feeds me information, and helps me to understand how I can bring something sensitive or intimate to the surface without a feeling of violent force.

For me, there is a feeling of collaboration with the spaces where works are shown, with the crowd, ideally from an equal stance. This is important to me. I often go talk to people at exhibitions. I often stay longer after the exhibition closes. I did that a lot in Hong Kong. We were having a daily six-hour durational performance, but quite a lot of the audience would come back, many times. They’d often behave differently, and when I was part of the performance I would interact with the audience, because a big part of the work is opening up a space for encounter to happen. The performer is a mode of agency in that situation.

In Hong Kong, I had a half-hour interaction with an audience member who had encounters with different performers, and, at some point, we were sitting next to each other, [for this] very gentle—but at the same time very scary—half of an hour, with our hands reaching out to each other. It didn’t feel like he reached out to me, it felt like there was a magnet between our hands that slowly drew us together. Every second was very much amplified because we were looking at it with such high concentration and the kind of nervousness that comes with the sense of distance and of closeness. These kinds of things amplify your senses. Your body, your physical being and your emotional being reveal a lot of information. After, he came to talk to me and he said: “You’re the artist, right? You were performing with me, and I wanted to tell you that before the back of our hands crossed each other, a string of your hair fell on the back of my hand and it felt like the heaviest weight I’ve ever experienced.”

WK: That sense of intimacy sounds very profound. I wonder how you think about creating spaces where performers and the audience are able to allow it to emerge? Obviously, intimacy is uneven ground, it can often be a place of anxiety, or of shame.

PD: Every work is different but, in getting people to do something, that was never my concern. I consider everybody who enters into a space, and that I am composing that space. And, their unity and their individuality, the distance between them, the distance they have with us as performers, is the proportion, the scale of how big the space is. This is something that intuitively becomes the nature of the work. I feel a bit like we’re putting a (metaphorical) lake in the space, and on the lake it can be windy, but we’re all in the same boat. So it’s not like they’re swimming alone. As performers, we’re providing them with boats for the water. Sometimes it’s more peaceful if they go faster, but for some it’s more peaceful if they decide to stay and enjoy the sun. Or, if it rains, they stay there fishing. But we’re at the same lake.

I want to create a potential sense of freedom. Not freedom imposed by others (a freedom that feels delusional) but a sense of comfort, a coming out of a discomfort. Once you start to find a pace, the work finds a pace, the rhythm of a work is very important. The pace and the rhythm coordinates a sense with all the moving bodies in the space—including the audience—and it creates a musicality, and once this syncs together everyone becomes more comfortable with their discomfort. Maybe it doesn’t happen immediately, but often they come back and confront that discomfort. And this kind of courage comes from inside oneself. I don’t make them do it, they do it themselves. And I think this is much more sustainable.

Pan Daijing: ‘Grief Lessons,’ 2023, installation view, Grazer Kunstverein // Courtesy of the artist

WK: Returning for a moment to the work ‘Grief Lessons,’ I wanted to ask about the history of drama and grief and tragedy. The title of the work implies a kind of procedural or instructive element. I wonder if you found any inspiration in the historical or classical works of tragedy in “dramatising” the sensations and emotions in and around grief?

PD: The philosophy of theatre is very attractive. The discourse of philosophers over the centuries, but as a context for my work, as a presentation of ideas it’s not something I feel close to. There’s a limitation in theatrical tragedy related to how free and how unfree we are in that context. There is definitely a theatrical element in the work, but when I think of tragedy I think of ancient Chinese poems I was asked to recite when I was a child. There is often this sense of sacrifice, almost a sense of beauty, a romance connected to tragedy, and that connects to the feeling of love—its possibility or its impossibility. Many cultures and many peoples have found ways of finding joy in suffering or in dealing with pain, it’s not unique to Chinese culture, and this is not because people love to suffer, but because that’s the only way to live another day. This phenomenon is something I’ve observed closely growing up, and I think this is more universal now. It’s not my intention to present a theatre of tragic narrative; that’s absolutely not something I intend to do. I compare the way I approach this work and storytelling to something like a scent: a scent triggers memory, but it’s ungraspable. It’s a framed moment or vision you can refer to, but the sense of it changes every minute, and it reacts differently for different people. It’s something I don’t want to control.

Exhibition Info

Haus der Kunst

Pan Daijing: ‘Mute’

Exhibition: Mar. 9–Apr. 14, 2024

hausderkunst.de

Prinzregentenstraße 1, 80538 Munich, click here for map