by Marley Heltai // Mar. 22, 2024

This year, artist duo Pakui Hardware—Neringa Cerniauskaite and Ugnius Gelguda—will represent Lithuania at the 60th Venice Biennale. For the last decade, they’ve been exploring the plasticity of bodies and their relationship to medicine and technology. Their work takes the form of futuristic and fragmented bodies—large orb-like structures made of plastic and metal, adorned with glass organs and positioned on luminescent fabric delicately arranged to resemble anatomical structures. Their installation ‘Inflammation’ will be presented as a conversation with paintings by the Lithuanian artist Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė and resembles an enlarged nervous system displaying the incendiary impacts of various societal structures upon natural and hybrid bodies alike. In our conversation with Pakui Hardware, we talked about their collaborative process, the conceptual foundation of their installation and the themes that inspired these works.

Pakui Hardware – Neringa Černiauskaitė and Ugnius Gelguda, portrait, 2020 // Photo by Arūnas Baltėnas, courtesy of Pakui Hardware

Marley Heltai: ‘Inflammation’ is a collaborative project involving three duos of artists, architects and curators. Can you tell us about the process for creating this work?

Pakui Hardware: Indeed this pavilion is a collective endeavor—not only the architects and curators were deeply involved, but also the pavilion’s commissioner Arūnas Gelūnas, the whole museum’s team as well (producers, communication department, designer, technicians) and many more! Thus it is important to stress their input in the installation. Our collaboration with the architect duo, comprised of Ona Lozuraitytė-Išorė and Petras Išora-Lozuraitis, began in 2016 when we were preparing for our solo show ‘Vanilla Eyes’ at MUMOK in Vienna. Since then, we have worked on a number of large-scale installations together, so the working relation is also a warm friendship. We’ve developed a dynamic and fruitful way of working that leaves space for both sides to experiment. As for the two curators of the pavilion—João Laia and Valentinas Klimašauskas—there is a long history of various projects and adventures together, as we have participated in a number of group shows that they curated individually. It’s crucial to have their input in mediating the installation and suggesting a number of ways to make it work in a more coherent way.

Pakui Hardware: ‘Inflammation,’ 2023 // Photo by Ugnius Gelguda, courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and carlier|gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

MH: The show explores the inflammatory impact of current social and economic conditions on human and planetary bodies. Could you elaborate on the conceptual basis of the installation and why you felt it was an important topic to tackle at this moment and in this context?

PH: The theme of inflammation came to us quite naturally as we have been exploring the relationships of bodies and medicine for quite a while now. We have tried to reveal in several previous installations how medicine and technology, for example, are never a thing of their own, but are always entangled in various other relations of dependencies, such as capital, corporations, state surveillance, etc. Inflammation connected the scales of human and planetary bodies as both are currently burning in one way or another, and as the authors of the book ‘Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice’ have shown, the main reason behind this chronic inflammation is (colonial) capitalism. However, with our pavilion we’re also trying to direct the attention to the inflammatory forces in our region, too. What is important, is that inflammation is also a historical or temporal issue as it is a consequence of histories of oppression and adversities that are inscribed into bodies and then travel from generation to generation.

Pakui Hardware: ‘Inflammation,’ 2023 // Photo by Ugnius Gelguda, courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and carlier|gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

MH: How does your work in the installation aesthetically address this theme of inflammation?

PH: The installation will itself become a little feverish kind of experience as it includes a newly built architecture in which an artificial landscape will grow, light beams that will scan the bodies of the sculptures, the visitors and the space alike as well as a new slowly pulsating sound work inspired by the signals produced by an MRI machine. The burning is inscribed in the materiality of the sculptures themselves, as they were born in sweltering heat that melted the aluminium and glass elements of the pieces. The shapes of the sculptures derived from the maps of the human nervous system—the vigorous lines of the nerves made of casted aluminium create spatial drawings that are suspended in the air with all of their fragility. Inflammation can also be encountered in the paintings of [deceased Lithuanian artist] Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, whose works are an integral part of the pavilion.

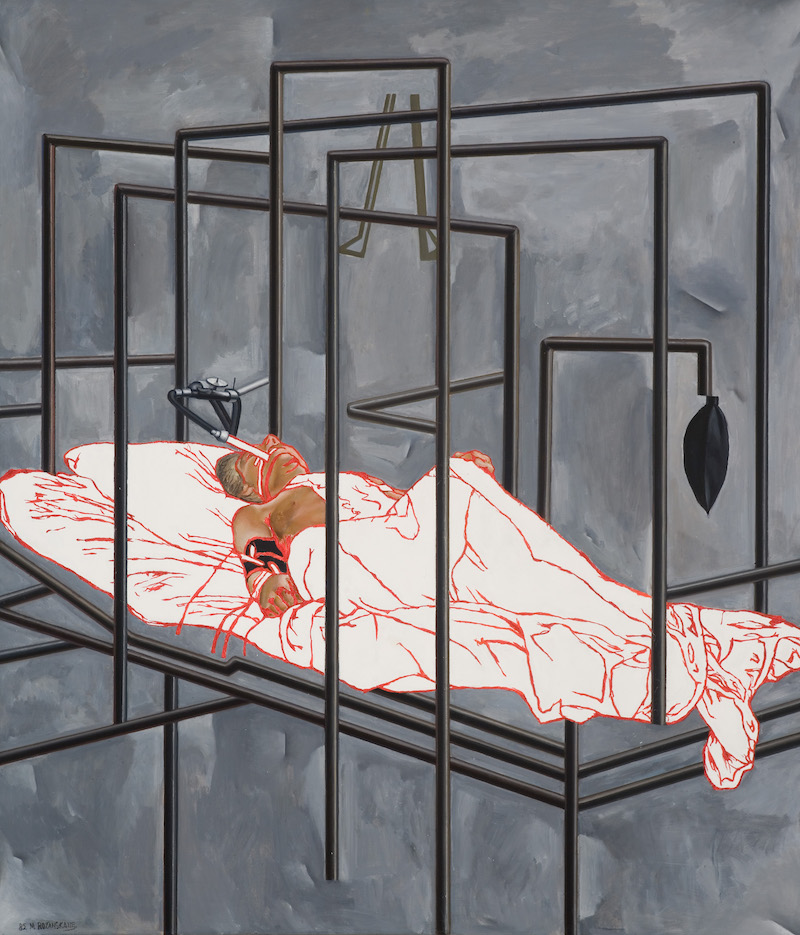

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė: ‘Disease,’ 1985, oil on canvas, 150 × 130 cm // Photo by Antanas Lukšėnas, courtesy of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art

MH: How does her work resonate with and inspire the themes explored in your own sculptures?

PH: We have been feverishly interested in Rožanskaitė’s paintings depicting various scenes from the medical field for about five years now. Although made in the 1970s and 80s, her paintings are strikingly contemporary—human bodies are often depicted in fragments, surrounded by technology, surgical draperies and tubes, and the scenes mainly take place in abstract backgrounds, as if taken away from time and space. It’s incredible for us how she managed to criticize larger systems of her time, but also technology, by revealing how those systems render human bodies and personalities into anonymous organs and body parts.

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė: ‘Heart Surgery,’ 1974, oil on cardboard, 240 × 170 cm // Photo by Antanas Lukšėnas, courtesy of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art

MH: In your statement, you say that “the installation invites the viewer to enter a certain state of mind and body, perhaps a little feverish and dizzy, in order to feel the web of life.” What kind of pathways for personal and collective healing do you hope ‘Inflammation’ will open up?

PH: We don’t expect the pavilion will bring a collective healing (it would be incredible, though!), but we hope that by mapping out the relations of interpendency, of porosity, of trans-generational traumas, the pavilion would guide the viewers to look for their own diagnosis of (chronic) inflammation, of perhaps even how their own people contributed to inflaming others, including non-human beings, as the pavilion considers human and planetary bodies alike.

MH: The architects created a “unified hybrid techno-organism” for the exhibition, including a surface of hybrid soil. How does this environment contribute to conveying the systemic nature of inflammation, in dialogue with your works?

PH: By introducing the ‘hybrid soil’—material that comes from a recycling plant and that will be returned to the plant after the pavilion—the installation attempts to connect the micro and macro scales, to show not only the obvious consequences of human activity, but also to look for ways to move forward, to look for hope in the midst of the slow burning state. This specific material was chosen by the architects, as opposed to the conventional materials that are used to shape landscapes in order to make the landscape as another form of hybrid body, a body that might too overcome inflammation.

Pakui Hardware: ‘Inflammation,’ 2023 // Photo by Ugnius Gelguda, courtesy of the artists, Lithuanian National Museum of Art and carlier|gebauer (Berlin/Madrid)

MH: The Sant’Antonin church hosts the pavilion for the first time. What significance does this venue have in relation to the immersive experience of ‘Inflammation’?

PH: This incredible church has been closed off to visitors for around 10 years, thus it has a meditative sense of dereliction, making it almost post-cultural. It is also a space for transgression and meditation. We hope it will bring another dimension to the installation. Faith is also a form of healing, yet at the same time religions often were the cause of “inflammation” themselves. There is an incredibly strong and interesting tension there.

Exhibition Info

La Biennale di Venezia

Lithuanian Pavilion: ‘Inflammation’

Exhibition: Apr. 20–Nov. 24, 2022

lndm.lt

Sant’Antonin Church, Castello 3300, 30122 Venezia VE, Italy, click here for map