by Alison Hugill // June 27, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Habitat.

The exhibition ‘Emerging Ecologies,’ which opened at MoMA last autumn, enacted a selective survey of the history of environmental thinking in American architecture during the rise of environmentalism in the United States, from the 1960s onward. Positioning itself theoretically in the wake of Rachel Carson’s influential 1962 book ‘Silent Spring,’ which documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of the pesticide DDT, the show foregrounded architectural responses to questions around ecology and what they can tell us about our present day conditions. We spoke to the show’s curator, Carson Chan, who was recently appointed inaugural director of the museum’s Emilio Ambasz Institute, the main goal of which is to promote dialogue and facilitate research around the relationship between the built and the natural environment. In our conversation, we touch on theories of ecology that inspired the show, historical instances of rewilding as architectural intervention and what lessons we can draw from past visionary responses to the degradation of our shared habitat.

‘Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism,’ 2023-24, installation view // Photo by Jonathan Dorado

Alison Hugill: The exhibition ‘Emerging Ecologies’ was conceived as a close look at architectural responses to environmental crisis in the US in the 1960s and 70s. Can you say a bit more about the concept of the show?

Carson Chan: The exhibition started with thinking about what it is that we want to accomplish at the Ambasz Institute. For me, one of the most important things I can do from within the museum, is give visibility to the conversation around the role architecture and the building sector plays in the environmental crisis. But, at the same time, to even have that conversation we needed a basis. Before we start a conversation about what we can do now or in the future, let’s take a look at what has been done already.

There was a point when ‘Emerging Ecologies’ was envisioned as a kind of global exhibition. Certainly, how architects responded to environmental questions in the 1960s and 70s is not limited to the US. But we wanted to focus on how the contemporary form of environmentalism, the mediatized version, really has its roots in the US at that time, with the attention that Rachel Carson brought to questions of ecology and humanity’s role in the ecosystem, in particular the detrimental role we have in changing the ecosystem. Her book ‘Silent Spring’ really brought that to public attention.

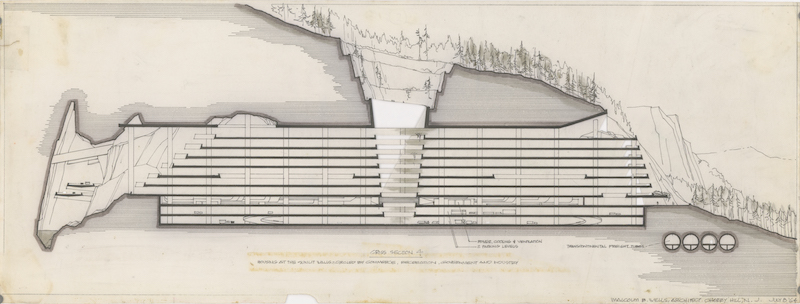

Malcolm Wells (American, 1926–2009): Untitled section drawing of an underground multi-use housing complex prepared for the article “Nowhere to Go but Down,” Progressive Architecture, February 1965. 1964, Ink and watercolor on vellum // Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art

AH: In addition to Rachel Carson, there are other theoretical references for this project. You lay out several “ecologies” conceived by Serge Chermayeff and Alexander Tzonis, lending to the plural form in the title of your show. What is your working definition of ecology for this show?

CC: ‘Emerging Ecologies’ stemmed from the Chermayeff / Tzonis definition of various stages of ecologies: pre-human (oceanic), on land and human-made. I was inspired by that concept to think of many ecologies emerging from particular concerns about the environment and humanity’s role in shaping it. The emerging ecologies within the exhibition can refer to many things: the different versions of the world that are proposed by the projects in the show. The exhibition aims to be a survey, though incomplete, of how architecture responded to the rise of environmentalism in the US. It does not endorse all those projects, but it is a recording or post-factum formation of a movement that allows us to gauge where we are in our conversations today in comparison to the past.

Some of the things, like NASA’s interest in building outer space colonies as a response to the degradation of the ecosystem—is this a response we want to take on today? I have my own personal opinions, but I think the exhibition is an invitation for visitors and readers of the catalog to consider for themselves.

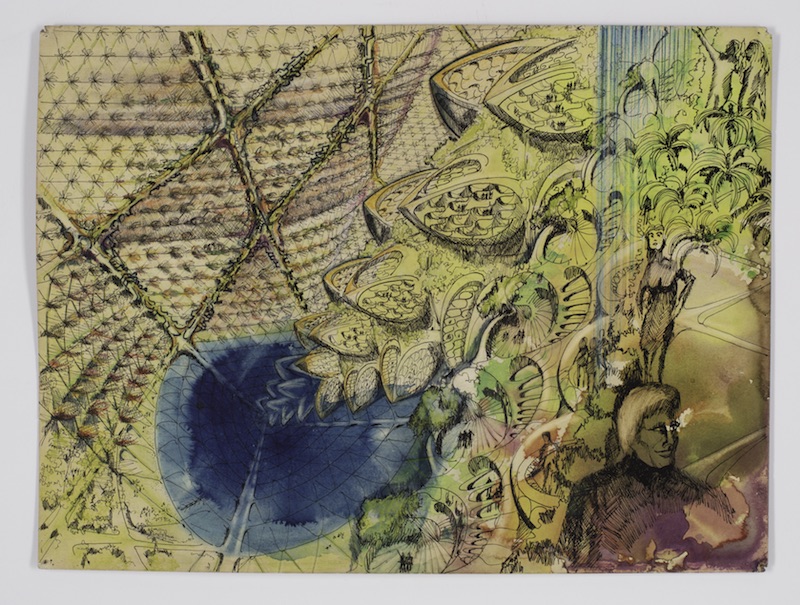

Glen Small (American, born 1937): ‘Biomorphic Biosphere,’ 1969–77, drawing of a flying house. 1973, ink and watercolor on paper // Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

AH: Can you talk about some examples of how architects at the time were centering the environment in their practices?

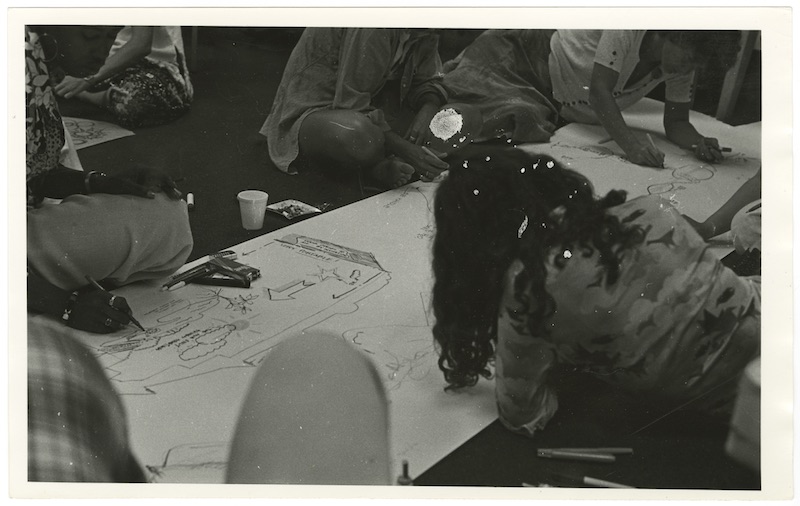

CC: The term environment was defined in many different ways throughout the exhibition. In the 1950s, the term really just meant surroundings or context. Later, after Rachel Carson’s book, the term environment got a more ecological dimension to it. Now, more recently, when we talk about environment, we think about climate. One work in the show that reminds us of the multi-valent definition of environment is the work of Phyllis Birkby and Leslie Weisman, and the workshops they did in the 70s called the Women’s Environmental Fantasy Workshops. They brought a large roll of paper to various places around the US and invited women to come and draw out their fantasy environments. In doing so they highlighted the fact that the environment was really defined through the male imagination. The built environment at the time, as it still is now, was almost entirely built by men. So giving women the agency to determine their own vision was an advocacy for an expanded idea of environment.

A Women’s Environmental Fantasies drawing session. c. 1975. Smith College // Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, Noel Phyllis Birkby Papers

AH: In the catalog of the exhibition, you mention an earlier show at MoMA that inspired this one: ‘Architecture without architects’ in 1964. The show dealt with pre-industrial, non-pedigree architects, many of whom welcomed vagaries of climate and topography in the way they designed and built. How does ‘Emerging Ecologies’ update or address this kind of architectural thinking?

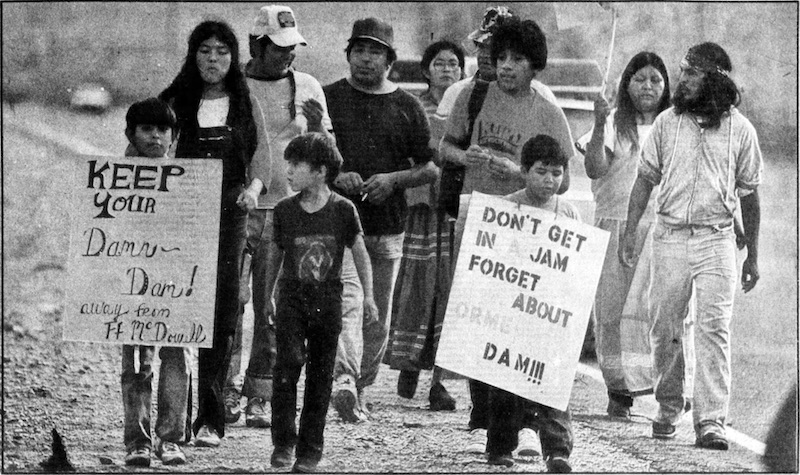

CC: One thing to highlight is that with any discussion of environment and ecological knowledge and building in North America, it’s impossible not to discuss the primacy of the indigenous people. One of the displays in the exhibition showcases documentation from the so-called Orme Dam protest, which was a protest by the Yavapai nation against a dam that was going to flood two-thirds of their land, but would have helped with the irrigation around Phoenix, Arizona. They eventually got the dam’s construction canceled. Preventing a structure from being built is as much architecture as building something. This is an example of how we want to use the exhibition to expand the definition of architecture beyond what people are used to.

A Berlin example that was in the exhibition was Oswald Mathias Ungers’ Green Archipelago project, which he did when he was teaching at Cornell University and brought summer students to West Berlin in 1977, with his teaching assistants Rem Koolhaas and Hans Kollhoff. They went to look at the depopulation of the city and tried to produce a scheme to present to the mayor at the time. After spending time in the city, their scheme ended up being to do nothing, to let the city de-populate; to let the forests grow back in the parts of the city that the people weren’t using, and to tend to the parts that people were using. Although Ungers and Koolhaas would never discuss it in such a way, as an environmental project, it’s an early example of rewilding.

Members of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation and supporters march through the Phoenix area to protest the proposed Orme Dam. From “Marching for Home,” Arizona Daily Star, September 24, 1981 // Photo by Ron Medvescek

AH: Rewilding has also become a hot topic in the art world lately.

CC: Yes. Glen Small, an architect active in the LA region, also thought about building a giant mega structure for the entire population of LA to live in and let the rest of the LA basin rewild. Malcolm Wells wanted humanity to live underground, so everything above ground would be left to plants and animals.

I am not endorsing these ideas necessarily, but we should see them as a provocation against which to measure our own conditions.

Malcolm Wells (American, 1926 – 2009): Sectional drawing of an earth-sheltered suburb. c. 1965, watercolor on paper // Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art

AH: There’s a future-oriented dimension to the show, but it’s decidedly coming from the past. We are now living in the future in question. What do you think we can learn from these positions today?

CC: The exhibition ends in the mid-90s and one of the reasons for that is the introduction of the LEED certification at that time, which codified architecture’s relationship to the environment at large and to climate. How we build and respond to the climate crisis has become a question of checking off certain boxes to attain certain certifications. One take-away is that maybe we need to re-diversify the field and learn from different ideas of what solutions can be, before we stick to this one set of codes. For me, the lesson from this show is to see the breadth of imagination and to celebrate it, and to recognize that environmental and ecological issues have long been deep concerns for architects.

Architecture and the building sector produce about 40 percent of the world’s greenhouse gasses. At this moment, we’re at a transition point between doing things the way we’ve been doing since the industrial revolution, and doing things in a new way. At this transition point we need to have as many different positions as possible.

Glen Small (American, born 1937): ‘Biomorphic Biosphere,’ 1969–77, view of interior reservoir. 1971, ink and watercolor on paper // Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art

AH: The Ambasz Institute has a subtitle—“for the joint study of the built and natural environment”—can you say more about what this distinction means for your work?

CC: For me, there’s just the environment. There’s no difference between the built and the natural environment. Humans are natural, we are part of nature, so what we build is as natural as anthills or beehives or birds’ nests. But I think it’s important to specify because we recognize that MoMA is an institution of public education, and for many people from the different publics out there, there still remains a distinction between the two. Part of the work of the Institute is to hold those two things and say: “what’s the difference? How can we reconcile them?” By insisting, through the work we do, that there is only one environment, we can show that by combatting the climate crisis we are not just trying to save the natural environment, but we are trying to save ourselves.