by Fionn Adamian // July 24, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Desire.

One visual effect dominates the superb caché of paintings by the American artist Miranda Holmes, which deal with the entanglement of self and other, subject and object. Her transparent films of paint, layered on top of one another, give you the sense of a porous spillage from one body to the next, as the scales of a human encounter tip from balanced intimacy to emotional oversaturation. Holmes’ paintings are concerned with desire as it informs not only romantic relationships, but platonic and familial ones as well. She is tuned in to the cloying insatiability of the need for attention as well as that suddenly encroaching desire to disown our relations and just be alone. When I arrived at Holmes’ studio for the interview last week, she had been working on a painting of a figure holding a bouquet of wheat (the autumnal color palette was meant to balance the more vibrant pieces of the collection). “I wanted the person to not just literally be giving these flowers, but also the sense of bounty that they’re carrying with themselves,” Holmes said. “The viewer can see the painting as a gesture of withholding this personal abundance behind one’s back or of offering it as a gift in front of one’s chest.”

These kinds of formal and thematic ambiguities—between interpersonal extension and withholding, between the flatness of the surface and the figurative game of depth perception—are always happening simultaneously in Holmes’ artwork, absorbing the viewer into the conundrums of desire that are represented on canvas. On first seeing Holmes’ new painting, I was inclined to identify the figure holding the bushel with the artist; I, at least, feel as if I’m receiving a gift whenever I give her work a careful look. But since Holmes and I have been pals ever since she spotted me at a vernissage sitting on the chair of a Franz West sculpture that was not, in fact, meant to be sat on, I’ve tended to take my critical judgment with a slight degree of suspicion: a layer of benevolent stardust always clings to the art that your friends make. It was no small relief, then, to learn that another friend of mine, with no relation to the artist, had left Holmes’ solo show with the same premonition as I did. “I’ve just seen the work of someone who is about to become famous.” In advance of her participation in the group show ‘Proem’ at FREYAalt, I spoke to Holmes about the place of drama in painting, abstraction, her artistic and theoretical influences and the featured theme, desire.

Miranda Holmes: ‘Loopers,’ 2024, oil and acrylic on canvas, 100×85 cm // Courtesy of the artist

Fionn Adamian: Desire is a concept that gets charged up with a romantic identification, but your paintings deal with intimacy in a number of relationship constellations, not just between lovers but also between friends and family members. Do you see a difference in the way that you approach these different subject materials?

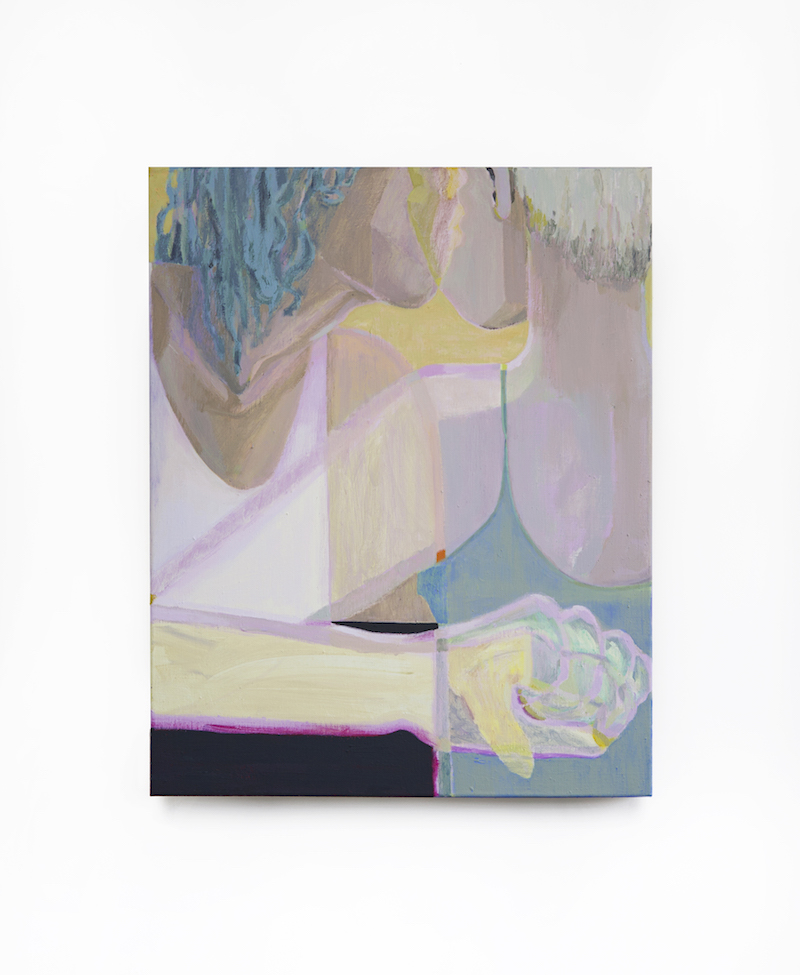

Miranda Holmes: With ‘Shell,’ the original ambiguity was whether it was a kiss or a conflict of rustling hands. I’ve been going into my paintings recently not knowing what the relationship is going to be. Maybe I have a slight agenda, but I’m kind of excited about the potential of letting the relationship unfold as I’m painting it. In the case of ‘Shell,’ I followed a color palette and a certain mark-making with the grip that leads most viewers to see this as a kiss rather than a conflict. I’m happy with that, but I hope that there’s always enough tension that it could flip the other way.

MIranda Holmes: ‘Shell,’ 2024, oil and acrylic on linen, 80x65cm // Courtesy of the artist

FA: It’s the kind of ambiguity that can only be done on a two-dimensional canvas.

MH: It goes into another motif that came up in this series: the ambiguity of whether the person has their arm behind their back or in front of them. The figures could be having a real connection, holding hands across a table, or the arm could be hidden and disarmed by whatever is going on in the interaction. I think you’re right that on the two dimensional plane, you can engage in this ambiguity because it is just one space, and there are some places where the arm is transparent and there are some places where it’s not. We’re always playing with that perception in painting. Or, in the case of an expanded contour line, I can really key into this moment of intra-action in which I’m thinking about the actual atoms between these people buzzing.

Miranda Holmes: ‘Narrow Time,’ 2024, oil and acrylic on linen, 80x65cm // Courtesy of the artist

FA: Speaking of which, in your artist statement you mention Karen Barad’s concept of intra-action from her book ‘Meeting the Universe Halfway.’ What do you mean by intra-action and what significance does your understanding of the concept have for your work?

MH: What I understand from Karen Barad’s work is just stunning to me: that on a quantum level there’s a continuous wave of particles that are always in intra-action with one another (not interaction because interaction already creates this difference between subject and object, like “me” versus “table”). But if we think about things in a continuous wave of these particles, our atoms are actually exchanging with one another. To me, it felt like there was something concrete there, as if science were bearing out this artistic research that I had been doing in grad school on the loss of boundaries between self and other. I’ve never necessarily been a very woo-ey person. But science is supporting this woo-ey stuff!

FA: I want to change tack slightly and ask about desire as a form of emulation. You finished grad school at Ohio State University in 2022. Over the course of your studies, what artists did you feel the most drawn to as examples for your own practice and why?

MH: I really admire Amy Sillman because she makes great paintings obviously and her background is rooted in feminism. If you look at some of her old work there’s this figure that’s very cartoonish and makes fun of itself but is carrying all of these burdensome shapes that are clearly, to me, her emotions that are wrapped up in abstraction. She was always grappling with a feminist body—whatever that means—that you’re always glimpsing but you never get full access to, one with feeling and motion and awkwardness. She always talks about awkwardness in her painting.

FA: She has this fabulous diagram of herself as an artist giving a talk in ‘Faux Pas,’ where she’s wondering whether the audience can see her clumped leg fat: “Possible round hair balls of fat showing between the pants and socks.”

MH: That’s her painting—she’s given a visual language to the awkward feeling of clumped leg fat.

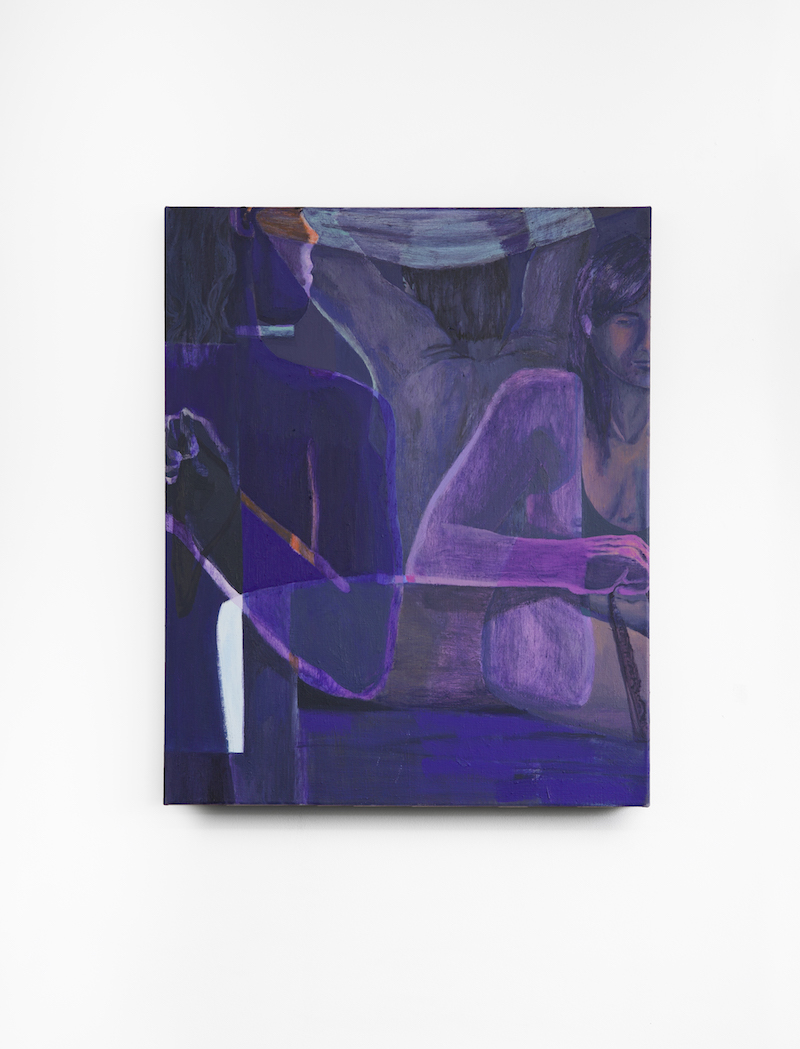

MIranda Holmes: ‘Borrowed Body,’ 2024, oil and acrylic on canvas, 95x80cm // Courtesy of the artist

FA: Something that you said about Amy Sillman made me think about your work…

MH: That you’re only just glimpsing the figure?

FA: Yes. It made me wonder why you rarely depict faces in your paintings. Often we’re mostly getting a sculptural cut of the torso.

MH: I figured out pretty early that having a face in contortion or disgust or happiness is never going to get the feeling across. I don’t want to say never, because obviously there’s examples, like Gustave Courbet’s crazy eyes looking out at the viewer, but I’m trying to get at feelings that aren’t so dramatic.

FA: That’s something that I deeply respect about your art—the theatrical static is sacrificed to get to this crystalline emotional image.

MH: If you look at my past work, you’d see this girl used to be dramatic! [Laughs] Maybe I got it out of my system, but I’m putting my trust into the fact that the viewer can get a lot out of the basics of painting. Here, I’ll show you how my canvas looks raw. I chose this material called a panama weave. It’s coarse and consistent. Usually, canvas would be a bit smoother than this. Maybe the viewer won’t even realize in the first 10 minutes, but if they’re living with this painting for the rest of their life, they’ll eventually notice that the actual canvas has this bumpy texture that is encouraging the sense that there are buzzing particles between the figures.

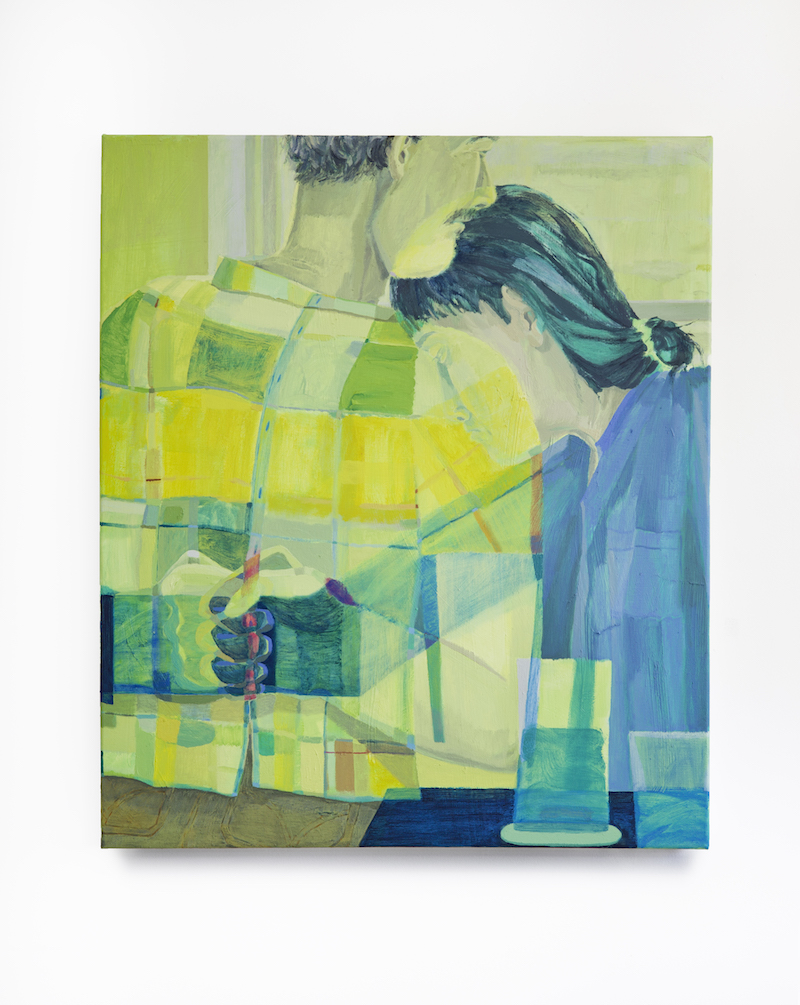

Miranda Holmes: ‘Double Check,’ 2024, oil and acrylic on canvas, 95×80 cm // Courtesy of the artist

FA: I was looking again at your painting ‘Double Check’ and thinking about your associations with abstraction. Even though it’s a material that we see on an everyday basis, this guy’s plaid shirt takes on this smart abstract function of segmenting the space of the canvas.

MH: The plaid shirt was fun because to me the figure became about a dad. It’s kind of funny because the zombie abstraction (or minimalism, we’ll call it) of these squares has such a male connotation, although that’s changing now. I was thinking that this unruly, unreliable dad has ended up really warping this abstraction.

FA: Or as soon as this idea of abstraction is draped on a human body it becomes contoured by the human’s warmth.

MH: That’s a really beautiful way of seeing it. It needed the human form to bring a softness to this more rigid abstraction. I’m trying to do a bit of both, to have this flat abstraction while also keeping this imagery. Sometimes it’s awkward.

FA: We’ll wait for the people to catch up to you.

MH: These paintings will outlast me.

Artist Info

FREYAalt

Group Show: ‘Proem’

Opening Reception: Thursday, July 25; 6–9pm

Exhibition: July 24–28, 2024

freyaalt.com

Glogauer Straße 16, 10999 Berlin, click here for map