by Sumugan Sivanesan // Aug. 13, 2024

Staged within an amphitheatre constructed inside the former power plant of Halle am Berghain, ‘The Soul Station’—a monumental immersive installation by Berlin-based artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley—centres around a cockpit made of a twin reclining seat fitted with a single sizeable controller. “Leaders,” who voluntarily take up the controller, face a large round screen, a portal into a labyrinthine game-space. Commissioned by LAS Art Foundation, ‘The Soul Station’ debuts Brathwaite-Shirley’s newest video game, unfolding over two parts: the first episode, ‘You Can’t Hide Anything,’ was launched on July 12th and the second, ‘Are You Soulless, Too?’ is scheduled to go live on September 12th. Set in the aftermath of a revolution, the main action in ‘You Can’t Hide Anything’ occurs inside a temple dedicated to “Bodyswappers.” Gamers are challenged to find and engage with six people inhabiting this graphically dense and detailed parallel universe, and then save them by choosing from a restricted set of conversational prompts, all within 11 minutes. A testament to the graphic limitations of the PS2 console (released 2000), gamers steer their way through throngs of polygon characters, past curious objects, between floating text and across vibrant textures.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘THE SOUL STATION,’ 2024, installation view at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation // Courtesy the artist, LAS Art Foundation, photo by Alwin Lay

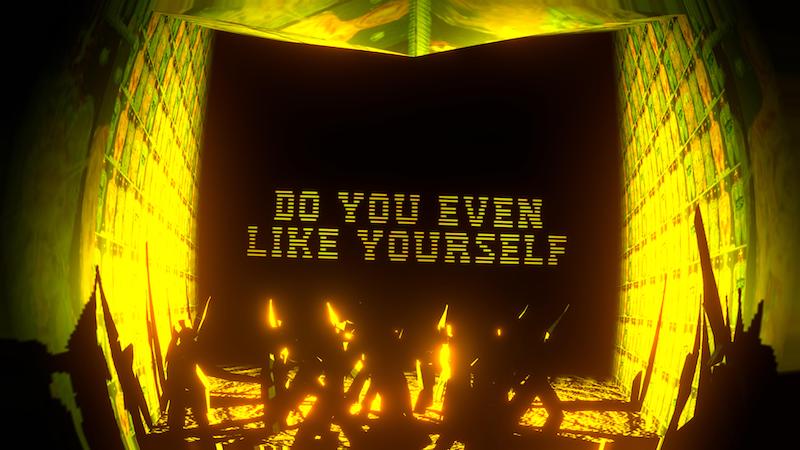

The game-space is a digital palimpsest, as Brathwaite-Shirley builds worlds by extending collages of day-to-day thoughts and encounters according to a personal rule that nothing entered can be deleted. A recurring motif of the artist’s oeuvre emphasises “Black Trans Life” that is buried; erased histories, dismantled spaces and bodies that have disappeared. Players have the option of pressing on tablets to learn about the game-space’s features, but at the cost of “wasting time” and thus lives. As players’ choices are projected on a large screen, this urgency begins to form the ethical and political core of the work.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘THE SOUL STATION,’ 2024, installation view at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation // Courtesy the artist; LAS Art Foundation, photo by Alwin Lay

Perched on tiered seating, touch screens at arms length, onlookers are encouraged to participate, shouting out advice and instructions to the leader. There is even the possibility—however remote—of physically taking over the controls. Brathwaite-Shirley advises that the game is nearly impossible to finish alone, suggesting collective decision-making as another level of interaction among those entranced by the screen. While the installation is stimulating and aesthetically captivating, it presents a deliberately dysfunctional situation reminiscent of the current state of democracy, as the artist herself acknowledged during a talk around the opening of the show: “A lot of the game is about watching someone play and hating what their doing, and shouting…but the sound’s so loud they can’t hear you. So you’re shouting and getting frustrated, but you’re powerless to change anything.”

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘THE SOUL STATION,’ 2024, installation view at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation // Courtesy the artist; LAS Art Foundation, photo by Alwin Lay

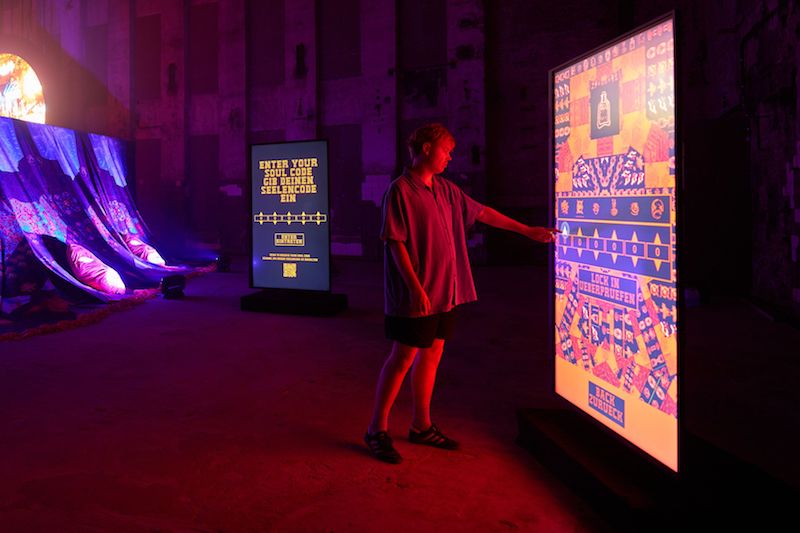

Two corridors leading to the arena house a selection of Brathwaite-Shirley’s previous games that resonate with ‘The Soul Station,’ including ‘Into the Storm,’ ‘Pirating Blackness,’ ‘Invasion Pride’ and ‘No Space for Redemption.’ A further expansion of gameplay can be activated via the touch-screen “Soul Stations” at various points around the Halle, where one is able to register for a “Soul Code” on a website. Players can then undertake further soul cleansing tasks online, and are exposed to “Soulglish,” a bespoke alphabet that is also printed on the fabrics draped around the furnishings.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘THE SOUL STATION,’ 2024, installation view at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation // Courtesy the artist; LAS Art Foundation, photo by Alwin Lay

In her catalogue essay, co-curator of the exhibition Mawena Yehouessi raises the notion of “soul loss” as a trauma-induced fragmentation of the spirit experienced as disconnection; as alienation. In the 1960s, with the rise of mass media, Guy Debord proposed an extension of capitalist alienation, as images mediated social relations in what he termed the “society of the spectacle.” By the early 2000s and the advent of the World Wide Web, this thread of analysis focused on the sociabilities that images circulating on networks produced, alongside what Harun Farocki named “operational images” that identify, track, activate and control; images that are sociable yet indifferent to the human gaze. In contrast, video game characters are images looping in game-space, like lost souls awaiting activation…or liberation? Indeed, Brathwaite-Shirley admits to being inspired by Augmented Reality Games, which spiral out of the screen, bringing gamers together to seek clues and solve problems in the physical world.

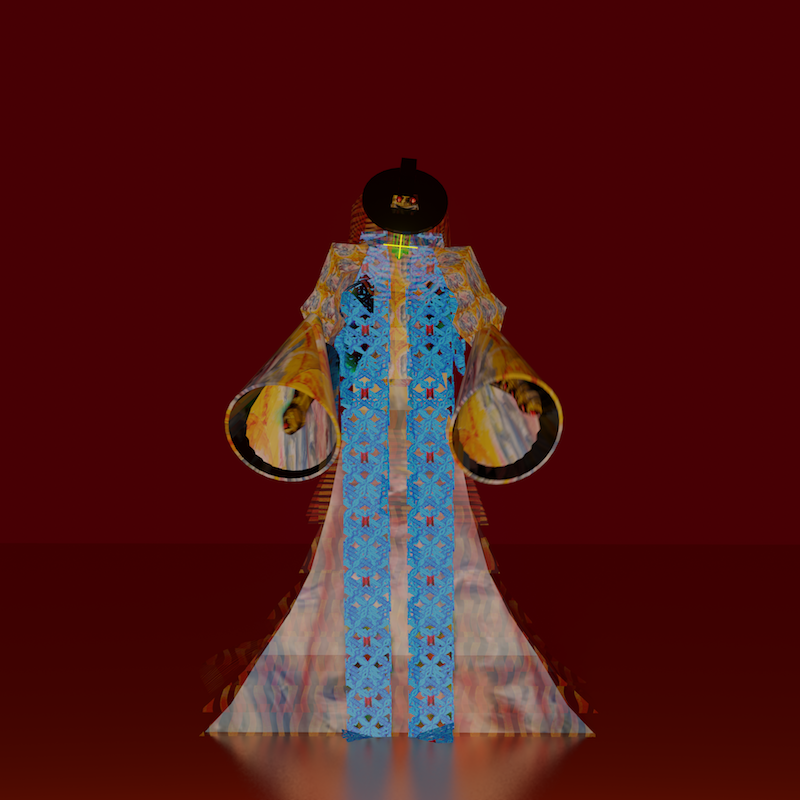

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘YOU CAN’T HIDE ANYTHING,’ 2024, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation // Courtesy the artist, LAS Art Foundation, © Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

As someone who often finds that video games feel disconnected from my desires for better human relations and for precious time away from screens, I encounter ‘The Soul Station’ as a series of contradictions. While gamers are challenged to save six people, to do so they must introspectively save themselves. Thematicising the crisis of democracy, ‘You Can’t Hide Anything’ proposes urgent collective action, yet, at the same time, Brathwaite-Shirley’s elaborate auto-fictional worlds, portals into buried Black Trans epistemologies, are absorbing and warrant close attention in themselves. These two demands appear to be irreconcilable within the parameters of the game.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘YOU CAN’T HIDE ANYTHING,’ 2024, commissioned by LAS Art Foundation // Courtesy the artist, LAS Art Foundation, © Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

Painted onto a shadowed triangular feature hanging down from the Halle’s concrete ceiling, an Eye of Horus oversees the arena. This symbol of ancient Egypt is equated with funerary offerings and those “given to deities in temple ritual.” A sign of protection, it suggests salvation for gamers who sacrifice their time and concentration.

Exhibition Info

LAS Art Foundation

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley: ‘The Soul Station’

Exhibition: July 12–Oct. 13, 2024

Admission: € 8

las-art.foundation

Halle am Berghain, Am Wriezener bhf, 10243 Berlin, click here for map