by Andrey Shental // Dec. 13, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Alien.

After decades of pernickety poststructuralist critique, nothing is neutral or pure anymore—especially in the space of contemporary art where every detail is amplified. The white cube, a vessel conferred upon modern and contemporary art since the 1930s, has been subject to particular scrutiny and quickly recognized as an ideological machine. From a decolonial perspective, one could say it is an example of epistemological violence. The chromophobia of museums and galleries, which suppressed all colors as alien to their sensibility, entrenched a Western-centric paradigm as universal, erasing other ways of knowing and being.

Victor Ehikhamenor: ‘The Penance Room,’ 2024, commissioned by Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), co-produced by Victor Ehikhamenor and HKW, installation view of the exhibition ‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses / Vergib uns unsere Schuld,’ Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) // Courtesy of the artists, photo by Hannes Wiedemann/HKW

Since the appointment of Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung as the new artistic director, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) has shifted away from its austere and encyclopaedic style of curating toward a less rigidly discursive approach, celebrating diversity, inclusivity and multi-perspectivism. One of the most apparent manifestations of Ndikung’s “curatorial justice” was the prominent use of uncompromisingly bright, clean and sometimes garish colours of the wall panels employed in the first three shows. To my surprise, the recent iteration, ‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses,’ reverted to the hegemonic exhibitionary model. The main space, now renamed after Indian sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee, retained its white walls, while a smaller one (Zakia Ismail Hakki) was transformed into the other popular format—the “black box.” Oversimplifying, one could say that the latter stresses the theme of forgiveness and confession, while the former emphasizes othering and trespassing.

However, this return to normality and achromatic status quo, when examined closely, is only apparent; it is undermined by the architecture of the exhibition itself. The upper part of the white walls surrounding the main hall is punctuated by protruding black horizontal beams. Known as torons, these are a defining feature of Sudano-Sahelian architecture. Here, they function not only as decorative elements but also as an epistemological intervention, disrupting the normative modernist carcass with insurgent indigenous forms. Moreover, besides the “whiteness” of this Western-centric container, the curators question the rectangularity of the space that dictates a certain logic of contemplation. “Hypotenuse,” which is mentioned in the curatorial statement as a form of transgressive walking, might be suggested by the Mexican artist Mariana Castillo Deball, who applied a reptilian ornament directly to the gallery floor (‘Crocodile Skins of the Days,’ 2024). This monumental structure, referencing tōnalpōhualli (the count of days in Nahuatl), twists beneath one’s feet, disrupting the usual upright navigation guided by visual stimuli. The placement of a non-European chronological system underfoot serves as a reminder of epistemicide—the systematic destruction of knowledge traditions, exemplified here by Spanish colonial domination.

‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses / Vergib uns unsere Schuld,’ 2024, installation view, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) // Photo by Hannes Wiedemann/HKW

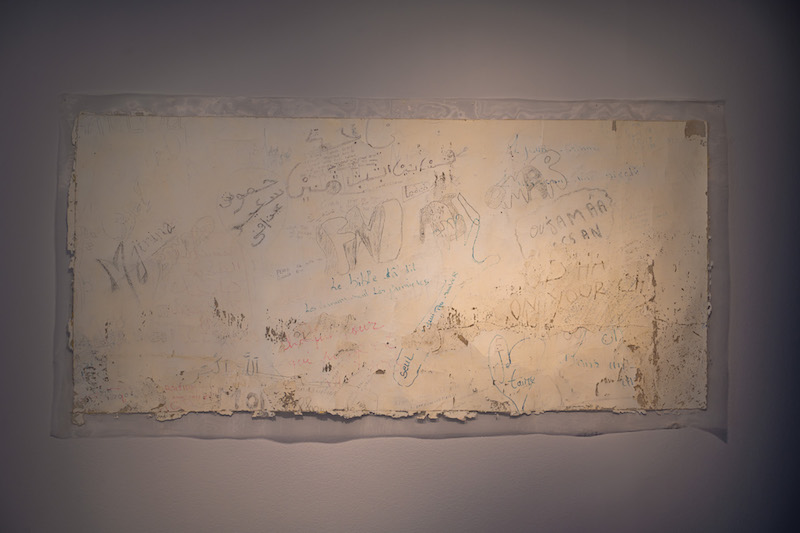

This formal deconstruction of the white cube’s semiotics, seen as never hermetically sealed from the outside, is reinforced by several artworks that engage with alien subjects through their content. Reminiscent of Hito Steyerl’s ‘Adorno’s Grey’ (2012) or Heidi Bucher’s method of “skinning” (Häutung), Patricia Gomez and María Jesús González’s long-lasting project ‘A Tous Les Clandestins’ (2014–2023) excavates the lost messages of refugees saved underneath the layers of paint on detention center walls. The two-channel video installation documents not only an actual archaeological extraction, but also its interpretation by one of the artist’s friends who, having once been detained in one of these centers, has since successfully settled in Europe. While the strappo technique is originally used to preserve the masterpieces of fine art, Gomez and González use it here to bring to light what is often considered the least significant—communication of extralegal subjects before or after their departure to Europe.

Patricia Gomez and María Jesús González: ‘Please don’t paint the wall. Charlie-D. Celda 4- I (II). CIE El Matorral, Fuerteventura,’ 2014, mural detachment on voile canvas, installation view ‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses / Vergib uns unsere Schuld,’ 2024, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) // Photo by Hannes Wiedemann/HKW

The three actual layers that are also present on the HKW’s white wall panels make a metonymic shift; they dislocate the viewer from the cultural institution in the center of Germany to the two secret detention centers in Mauritania and Spain. This dislocation into the “outside” of the gallery world may suggest that philosopher Giorgio Agamben was right: concentration camps that render certain lives as negligible are not an anomaly within Western legal culture but rather a part of its definitive structure. While some of the addressants might have been expelled or even died crossing the Mediterranean Sea later, this piece confronts the viewer with the brutal reality of cultural artefacts. It is not these persons themselves but only their stories, disembodied and consecrated as artistic practices, that are wanted in Europe. For, contrary to the intentions of the artists, these fragile wall fragments get absorbed into the aesthetic machinery of the white cube.

Larissa Sansour’s film ‘Familiar Phantoms’ (2023), co-produced with her partner Søren Lind, explores the subject of alienness through a less forensic and more introspective approach. This poetic meditation on the nature of human memory features close-ups of material objects, archival footage and staged recollections of the artist’s family history in Bethlehem, part of the Israeli-occupied West Bank. The film offers an alternative view of secular Palestine—one absent from the dominant, often dehumanizing German narratives—presenting it as a site of struggle for political liberation. Through the voiceover, we learn that the artist’s family members were forced to leave their homeland, migrating across South America, Egypt, Jordan, Iran and the USSR as political climates shifted. Without lapsing into revictimization, the film conveys the tragedy of Palestinian displacement and decades-long homelessness, evoking empathy for its protagonists. However, unlike ‘A Tous Les Clandestins,’ which metonymically dislocates the white cube to its exterior, ‘Familiar Phantoms’ is presented inside ethereal black cylinders, levitating at the center of the exhibition. This decision to present this work behind the curtains—again, the “hypotenuse” that obstructs the regular routes—lends it a subtly confessional and apologetic tone, an impression that contrasts with the exhibition’s overarching message that there is no need to seek forgiveness for being who you are.

Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind: ‘Familiar Phantoms,’ 2023, 1-channel-video, sound, 42‘, installation view, ‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses / Vergib uns unsere Schuld,’ 2024, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) // Photo by Hannes Wiedemann/HKW, courtesy of the artists

At a time when expressing pro-Palestinian views can lead to de-platforming, job termination or budget cuts, this exhibition presents works by three Palestinian artists (also including Ahlam Shibli’s photography and Sliman Mansour’s posters). Hosted within a central German government-sponsored art institution, this curatorial choice is in itself a political statement. Yet, it is symptomatic that the most relevant film, ‘Familiar Phantoms,’ is hidden behind the curtains within the open exhibition space, while the gallery as a whole is isolated from the broader social world. This dual act of seclusion can be interpreted as a metaphor for the current German political climate. When discussions of ongoing atrocities are silenced, alternative narratives are confined to the past or framed as art.

Absorbing traditions of institutional critique and decolonial theory, ‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses’ thoughtfully squeezes the remaining potential out of the white cube, subjecting this seemingly neutral container to uncomfortable questions and making metonymic shifts to what lies outside—displacements, genocides, encampments and segregation of “alien” populations. However, when it directly approaches pertinent political issues, it swiftly folds endlessly into semiotic self-reflection and epistemological analysis. While these issues are undoubtedly significant, the show leaves me with the question: has the legacy of poststructuralism, which argues that any enclosed space is never neutral but always shaped by external reality, trapped cultural workers in an endless reflection on the politics of the white cube, in lieu of political action?

Exhibition Info

Haus der Kulturen der Welt

Group Show: ‘Forgive Us Our Trespasses’

Exhibition: Sept. 14–Dec. 8, 2024

hkw.de

John-Foster-Dulles-Allee 10, 10557 Berlin, click here for map