by Mats Antonissen // Dec. 17, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Alien.

Gisèle Vienne’s dolls stare. They do so impassively; at the gallery’s floors, at the ceilings, at the walls or out its windows. They never lock eyes, despite always existing in each other’s vicinity. Their postures are poor, hair unkempt, clothes oversized. From afar they look shy; sad from up close. In the corner of their eyes water—translucent paint—pools. Tears stream down a few faces, unrestrained. What’s ailing these not-quite-adult-sized, mute figures? Vienne doesn’t say, either. The artist prefers staging silence over explicating it. It’s up to us, viewers of her three-part Berlin retrospective, to attend to the quiet and make sense of it.

Gisèle Vienne: ‘Puppen, 2006-2024,’ installation view, ‘Ich weiß, daß ich mich verdoppeln kann. Gisèle Vienne und die Puppen der Avantgarde’ at Georg Kolbe Museum, 2024 // Photo by Enric Duch

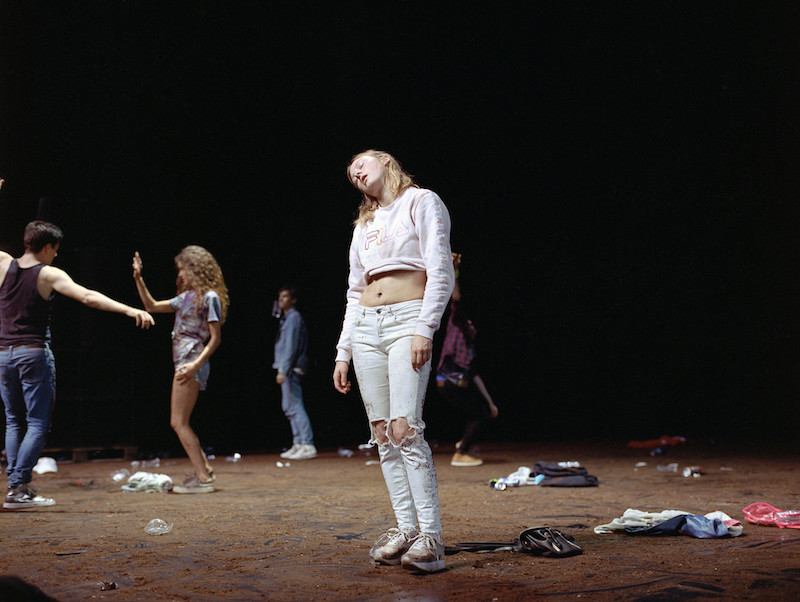

The same empty looks seen in the exhibitions at Haus am Waldsee and Georg Kolbe Museum, recur in the dance performance ‘Crowd.’ The piece, originally from 2017 but restaged at Sophiensaele for four nights in November, simulates a ‘90s rave with help of the era’s soundtrack and clothing. For about 100 minutes, 15 partygoers move in skillfully synchronized slow-motion and staccato. Stupor plays no small part here either, but it appears alongside other, more vivid mental states. Fear and elation, for example, which, it’s worth noting, usually occur when the performers’ eyes meet.

Gisèle Vienne: ‘Crowd,’ 2017 // Design copyright DACM / Gisèle Vienne, photo by Estelle Hanania, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2024

Speech is as irrelevant here—the techno mix resounds at true-to-club volume—as it is in the gallery. Communication happens exclusively through facial expressions and the movement of bodies, with their stylized trajectories and often frozen, grotesque grimaces and poses. A back and forth ensues between something resembling robotic automation and true human vulnerability, providing ‘Crowd’ with an undercurrent of threat and suspense, a feeling that, characteristically, never gets resolved. The performance doesn’t come across as a nostalgic ode to the rave as lost utopia, but rather uses the medium of the party to display one of Vienne’s central concerns—the difficulty of allowing the full range of our feelings, while existing in relationship to others at the same time. Looming large here is the threat of self-alienation that comes with adapting to cultural norms of (self-)expression.

Gisèle Vienne: ‘Crowd,’ 2017 // Design copyright DACM / Gisèle Vienne, photo by Estelle Hanania, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2024

This is likely why Gisèle Vienne is preoccupied with adolescence, too. It’s a phase of life in which emotional contradiction is experienced to a critical extent, and its extreme fluctuations are dictated largely by the relationship between self and peers. Art and entertainment are infatuated with youth culture, but that’s largely because of its supposedly unmatched passions and eccentricities. Quiet and inhibition are less alluring than euphoria and destruction. But it’s precisely in these ambiguous qualities that Vienne carves out her niche.

Gisèle Vienne: ‘PORTRAITS 44/63,’ 2024, series // Photo by Gisèle Vienne

‘63 PORTRAITS 2003–2024,’ the series of photographs presented in grids at Haus am Waldsee, is another example of the way in which Vienne leverages situational uncertainty to cryptic effect. The square portraits hung across three consecutive walls of the estate are classically composed with each doll seated center-frame in front of a grey screen. Shot together with photographer Estelle Hanania, these are medium format film photographs of high quality and brightness that enable close scrutiny of the puppets’ materiality, the layers of acrylic covering their resin faces. But accompanying a legible surface is, again, a murky interior. We recognize the downcast glances and youngish countenances hidden by hoods and hair. We still don’t know the source of their existential malaise, but there’s an apparent struggle for composure in front of our eyes and that of the camera. Like putting up a front for the school photographer, while experiencing anguish inside.

Gisèle Vienne: ‘PORTRAITS 48/63,’ 2024, series // Photo by Gisèle Vienne

Youth appears here more of a means than an end. Just like the rave, it’s an angle through which to approach the interaction between individual and collective emotional experience, a thorny bargain that ultimately transcends any one age bracket. The artist describes her artistic method as a “thinking method,” and it’s evident that sustained observation and consideration precede the creative act. Whether it’s performance, sculpture, film or photography; the different pieces of this retrospective are united by over two decades’ worth of meditation on youth culture, emotion and community. At the same time, though, the work seems to herald the dangers of excess thought. Too much of it can lead to torpor, as exemplified by the stiffened bodies of the puppets and performers.

Gisèle Vienne: ‘TRAVAUX 2003–2021,’ installation view, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, 2021 // Photo by Martin Argyroglo

Vienne’s practice is de facto collaborative for a reason. Her mother, artist Dorothéa Vienne-Pollak, introduced her to puppetry and they construct dolls together to this day. The retrospective also contains collaborations with philosopher Elsa Dorlin, photographer Estelle Hanania, writer Dennis Cooper, director Zac Farley, composer Caterina Barbieri and, of course, the ensemble of dancers. The method might be part of the message here. Critique of the status quo is necessary; it comes naturally if you pay attention. But change, on any scale, requires moving from analysis to action, which necessitates forming alliances. Alienation, whether it’s from society or yourself, can be fertile ground for partnering with those who experience something comparable. In the world of Gisèle Vienne, all it takes for one troubled subject to touch the next is reaching out.

Exhibition Info

Haus am Waldsee

Gisèle Vienne: ‘This Causes Consciousness to Fracture – A Puppet Play’

Exhibition: Sept. 12, 2024-Jan. 12, 2025

hausamwaldsee.de

Argentinische Allee 30, 14163 Berlin, click here for map

Georg Kolbe Museum

‘I Know That I Can Double Myself: Gisèle Vienne and the Puppets of the Avant-Garde’

Exhibition: Sept. 13, 2024-Mar. 9, 2025

georg-kolbe-museum.de

Sensburger Allee 25, 14055 Berlin, click here for map