by Mia Butter // Mar. 10, 2025

As part of the EMOP–European Month of Photography, the Akademie der Künste in Berlin presents the long-term project ‘Ein Dorf’ by Ludwig Schirmer, Werner Mahler and Ute Mahler. Curated by Marit Lena Herrmann, the works of each photographer come together through an exploration of a small town in central Thuringia. Documenting daily life in Berka over 70 years, an initially unplanned project emerged through the efforts of Ute Mahler and Werner Mahler. Featuring over 120 photographs, the exhibition at Akademie der Künste tackles the question of time, identity and the only constant—change.

Ludwig Schirmer: Image from ‘Ein Dorf,’ 1950-1960 // copyright Ludwig Schirmer/OSTKREUZ

Mia Butter: I read about your series and how the story of ‘Ein Dorf’ (A Village) came to be, namely with the discovery of your father, Ludwig Schirmer’s, negatives. Could you tell me a bit more about what ‘Ein Dorf’ is about and the ideas behind it?

Ute Mahler: Well, we only realized afterwards how significant this place is to me and the family. I was born there, my father was a master miller, and I was 14 when he moved the family to Berlin to become a professional photographer. But we always had this connection to the place because the mill was still standing and my grandparents lived there. We always used the house for holidays or as a place to work. I took a lot of Sybille fashion photos there. So this link with Berka was never really broken. Werner photographed his thesis work there in 1977/78, while he studied at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig.

He didn’t know the photos my father had taken in the 50s. We only discovered this batch of early photos after his death, when we were sorting and organizing his estate. It was incredible because this doesn’t happen often in life. It felt like a treasure, it was unbelievable. We immediately recognized that there was something very special about the photos, and they weren’t really organized. In some cases, there were only the negatives.

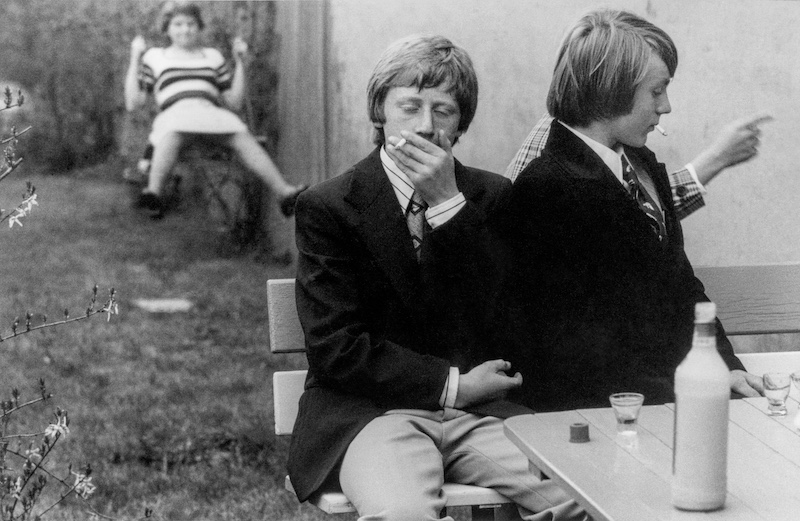

Werner Mahler: Image from ‘Ein Dorf,’ 1977-1978 // copyright Werner Mahler/OSTKREUZ

MB: Werner Mahler photographed Berka in the 70s, and then 20 years later again in the 90s, on commission from Stern for their special edition 10 years after the reunification. Was the connection to Ludwig Schirmer’s work initially clear?

UM: No, we didn’t see that connection. I find it really amazing that some things take time. We discovered these photos and thought, “How unfortunate that he [Ludwig Schirmer] couldn’t experience these being exhibited.” He would have been incredibly proud. But we only realized, some years later, that it would be interesting to connect the 50s with the 70s, and then perhaps the 90s. We knew that each body of work was unique, had its strengths and its own approach. For my father, you could say he was like a flâneur. He just photographed whatever he saw. Werner, on the other hand, approached the theme of the “village” in a much more systematic way. It likely came from the fact that Werner wanted to be a reporter back then. He didn’t want to document with individual images but rather with smaller, almost reportage-like stories.

Werner Mahler: Image from ‘Ein Dorf,’ 1998 // copyright Werner Mahler/OSTKREUZ

MB: What was your approach in 2021, when you returned to photograph for the ‘Ein Dorf’ project, now with the knowledge of your father’s and your husband’s images?

UM: The three existing works at that time were done 20 years apart. It became clear at some point that now, 20 years later, a new series had to be made, and I had to do this one alone. Werner and I have exclusively worked together, under one authorship, since 2008. I thought we could do it together again, but then Werner decided, this was my part. [laughs]

Werner Mahler: I had already photographed two bigger series in Berka. So, it was logical that Ute took her 2021/22 Berka photos alone.

UM: And then it was very complicated because it was during the pandemic. No festivals were taking place, and I barely saw anyone on the streets. But I didn’t want to delay it indefinitely. Sometimes, when a theme is there, you have to pursue it. And we couldn’t foresee whether things would ever improve with the pandemic. […] For me, it was a huge challenge because I knew the amazing photos my father had taken, the really great ones from Werner, and I also knew that life in Berka looked very different now. Not just because of the pandemic, but overall, being together looks very different now.

Ute Mahler: Image from ‘Ein Dorf,’ 2021-2022 // copyright Ute Mahler/OSTKREUZ

WM: She had to make appointments with everyone. No one would just show up; she had to go into houses, knock and say, “Hi” and agree on a time to take their photo. Getting in contact with people was a bit easier for her because she was born there, and almost everyone knew her, even the young people. But it was still a challenge.

UM: Yes, that was definitely a big advantage. But still, I had to ring the doorbell, knock and ask. I then thought about how I could implement this big project. I realized I could only approach it very personally. I couldn’t document it in the way Werner and Ludwig had, because it doesn’t exist in the same way anymore, so I had to find my own approach. For me, it was a personal one. […] I know I had this longing for the landscape, or for certain smells and that’s what I had been looking for, so I took landscape photos that reminded me of my childhood. When it came to the portraits, I thought I would focus on the young people who were about the same age I was when I had to leave. Because it’s always that question, “What would I have become if…?” And you never get an answer.

Ute Mahler: Image from ‘Ein Dorf,’ 2021-2022 // copyright Ute Mahler/OSTKREUZ

MB: Do you plan to continue this and perhaps photograph in Berka again in a few years? Is ‘Ein Dorf’ now considered finished?

WM: The works, as far as we are concerned, have always been created almost exactly 20 years apart.

UM: We won’t manage another 20 years anymore.

WM: We’ll be 95 then. You could say we’ll look at it again in 10 years, but I wonder if the differences will be as significant. This theme won’t escape us, though.

UM: I think it’s a good question because of the extreme political developments that have happened recently. We’ll have to see how things evolve. If there are really major changes, I think we would need to revisit it.

WM: It’s not a political project. It’s a social project, and in the book’s texts, which you can read, at least three of them, it’s clear that you can find the same things in West Germany, Europe or the US. So, we’re not making a statement about the political situation in our small country, but rather a social investigation, if you will.

UM: I see it differently. For me, everything is political. Even the social aspect has a political component. But of course, it’s in Thuringia, in the center of Thuringia, the “green heart of Germany” and these elections were really disturbing. So, we have to watch what happens now. I mean, the first photos by Ludwig Schirmer were taken right after World War II. Then came the land reform, then the Wall, being closed off, the opening of the borders and Thuringia becoming part of the Federal Republic. It’s a lot for the people to process, and it wasn’t a smooth transition. We still have huge issues with communication between people. We just have to see what happens now, and in that sense, you’re right—it is an ongoing project.

Exhibition Info

Akademie der Künste

Ute Mahler, Werner Mahler and Ludwig Schirmer: ‘Ein Dorf 1950–2022’

Exhibition: Feb. 28-May 4, 2025

adk.de

Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin, click here for map