by Dagmara Genda // Apr. 4, 2025

An amusing anecdote told by Pamela Z at this year’s Maerzmusik summed up the latest iteration of the festival quite well. Over 10 years ago, she created a version of Meredith Monk’s ‘Scared Song’ that only existed as a studio arrangement for a tribute CD. When Monk asked her to perform it live, she could not say no to the legendary artist’s request and, of course, agreed. Then, with some measure of panic, she scrambled to reformat the piece into a performance over the course of a week. The final work, Pamela Z explained, is not exactly what was mixed in the studio, but “pretty close.” Nowadays even music that we assume can be performed live—like the piano pieces played by the classical world’s shooting star Víkingur Ólafsson—are composed of such complex mixes (he plays the same piece on different pianos so as to achieve an impossible-to-perform sound in the studio) that they can only exist as ethereal digital files—pure sound without form. And yet music, like text, like images, does have a place, a context and a lived reality, though prolific digitalization makes us apt to forget that. And while this year’s festival got off to a somewhat shaky start, in the end it raised a number of interesting questions. How does space and performativity affect our perception of sound? How do we, as listeners, ourselves perform the sound that we hear?

Pamela Z: ‘Other Rooms’ at MaerzMusik 2025, Haus der Berliner Festspiele // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Maybe ‘Melencolia,’ Brigitta Muntendorf’s opening night “Gesamtkunstwerk” at the Haus der Berliner Festspiele, tried to tackle these issues, but it came off as a potpourri that foreshadowed the scattered tone of the festival’s opening days. The extravagant production, consisting of multiple live and recorded projections, green screens, fanciful props and cartoonishly costumed performers, was likely supposed to elicit some sensation or contemplation of melancholia, perhaps through the (anti-)social malaise caused by digital and medial alienation, but it only served to alienate the audience from the work itself. Quotes about sadness, ranging from poets to sports commentators, and even the prince of melancholy himself, Leonard Cohen, were stitched together into a pastiche of sung, screamed and squeaked out lyrics. Accompanied by a panoply of visual references—a kind of toxically fluorescent, post-internet color scheme, costumed performers that seemed to belong to Disney and Saturday Night Live trapped within a cycling 3-channel video installation that one was not allowed to leave—were tropes that we had often seen before. Though one might be able to sensibly describe the rationale behind the work, the end product fell flat, as if the idea was too ambitious for its execution.

Brigitta Muntendorf: ‘Melencolia,’ 2022 at MaerzMusik 2025, Haus der Berliner Festspiele // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Similar aesthetic strategies were put to use in Jennifer Walshe’s ‘Minor Characters,’ such as inclusion of projection, text and recitation. In contrast to ‘Melencolia,’ however, the much smaller production held the audience’s attention throughout. Co-authored with composer Matthew Shlomowitz and accompanied by Ensemble Nikel, the Oxford University professor presented a meticulously balanced work of textual fragments, clichés and internet quotes, but ones that subsequently subverted themselves via dramatic escalation and climaxed in absurdity. The texts projected behind Walshe usually captioned her vocal acrobatics via different fonts and colours, all of which had their own associations of source and credibility—themes highlighted through references to internet trolls and sexual harassment. The piece was smart, even too smart in its ultimately correct if provocative positioning, as well as aurally captivating, as when Walshe seemed to hysterically argue with an equally manic saxophone.

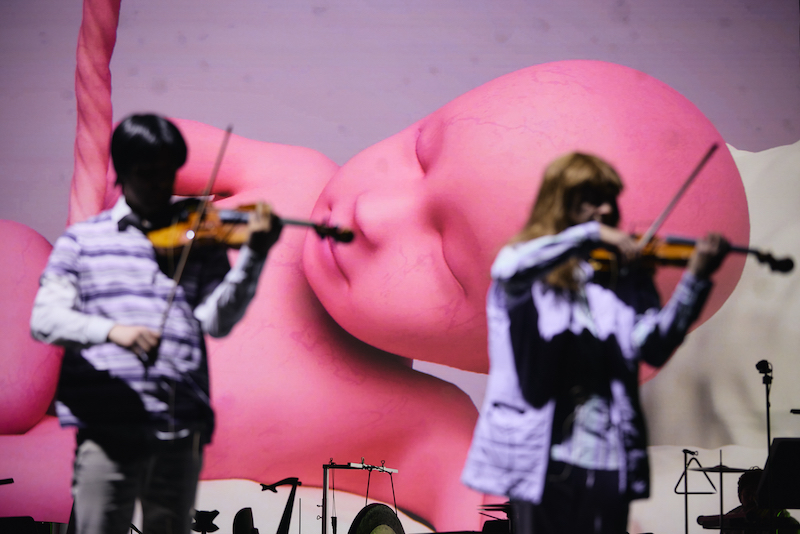

Synaesthesis: ‘The Urban Tale of a Hippo,’ 2022 at MaerzMusik 2025, Sophiensaele // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Ute Wassermann’s premiere ‘The Art of Camouflage’ privileged a more auditory approach, though in the end failed to deliver the unique intensity for which the artist is known. The work featured a row of four other performers, more or less reproducing Wassermann’s signature animalistic and exquisitely unearthly sounds. In this case, however, more was less, since it is contrast rather than multiplication that highlights Wassermann’s originality. The fog, drones and invitation to loiter around during the following performance, ‘The Urban Tale of a Hippo’ by ensemble Synaesthesis, served to distract from rather than heighten what was anyway a disjointed musical experience. Most disappointing was the promising ‘POETICA’ by Chaya Czernowin, performed a night later. It made such extensive use of amplification that one might wonder if live performance was necessary for anything other than optics. The strings were prerecorded and one could not always differentiate between the electronic effects and soloist Steven Schick alongside Les Percussions Strasbourg, an act of simulation that might either be understood as proof of skill or a lack of sonic originality. The changing spectrum of lighting and glowing rubber drumsticks created a kind of carnivalesque seduction which, if last year’s performance from the ensemble is taken as proof, seems to be a running theme for the group. For Maerzmusik 2024, Les Percussions de Strasbourg staged an over-the-top, dystopian version of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s ‘Musik im Bauch.’ The show was so slickly produced that one could just as well forget the music.

Chaya Czernowin: ‘POETICA,’ 2024 at MaerzMusik 2025, Haus der Berliner Festspiele // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Enno Poppe’s ‘Streik’ represented a turning point in the somewhat laborious pace of the festival, by simply staging the spectacle of 10 drum sets played by 10 musicians. Simply lit, the musicians acted as one soloist. They beat out mounting, rolling and stuttering rhythms, pulsing between order and chaos, virtuosity and practiced ineptitude. A truth to materials, both visual and audio, also marked Mazen Kerbaj’s world premiere of ‘With a Little Help From My Friends II: From One War to Another,’ in a performance series at Silent Green that did justice to the legacy of the festival. Performed by the composer with trumpet and crackle synth, movement and position formed the formal foundations of the loud, sometimes dramatically pained and painful piece. Kerbaj started by standing far behind the audience and playing a swinging trumpet, whose mouthpiece was elongated with a plastic tube. Slowly, he started to make his way toward the front of the room. Later, increasingly dense electronic crackling and recorded trumpet sounds escalated into strained, amplified and distorted breathing. The work ended with the performer moving back into the audience, holding two small handheld speakers that he swung around to dramatically contort the emitted sound. Kerbaj is from Lebanon; the context of the piece is not difficult to understand in light of Israel’s continuing—and in many respects, illegal—bombardments of his home country, as well as Palestine. But even without the backdrop of tragedy, his techniques allude to distorted messages, the phenomenon of speaking past each other, as well as the very subjective, visceral act of hearing.

Enno Poppe: ‘Streik,’ 2024 at MaerzMusik 2025, Haus der Berliner Festspiele // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

The potential of performance and position was most directly addressed by Bastian Zimmermann’s dramaturgy for the ‘Salon of Touch’ and ‘Finale,’ which employed two different if related strategies. The ‘Salon of Touch,’ with music programmed by Kuba Krzewiński and stage direction by Alienor Dauchez, was a playful, one-hour series of short performances exploring the body through and within sound. The bar of the Haus der Berliner Festspiele was converted into a small venue, where the audience was invited to take off their shoes and have their hands washed in iridescent, shell-like bowls by musicians wearing translucent latex clothes. Large swathes of beige-colored latex was also draped over the windows and a smaller piece was hung as a banner from which a row of opalescent discs were suspended. The atmosphere was something between a new age wellness center and a sex club, though the entire set-up was more reassuringly polite than transgressive. The set began with ‘A Face Like Yours’ by Aviva Endean, a delightfully surprising composition wherein the audience wore earplugs and was instructed via video to touch, tap and slap their own faces, which they dutifully did. In unison everyone experienced their own private composition. Because of the ear plugs, the sounds of touch were amplified within the container of the body, as if the rhythms were coming from within. At the end of the piece everyone was instructed to hum a steadily rising pitch and take out the earplugs. A shy, collective whimper could then be heard, a tentative return to collectivity after an insular listening experience.

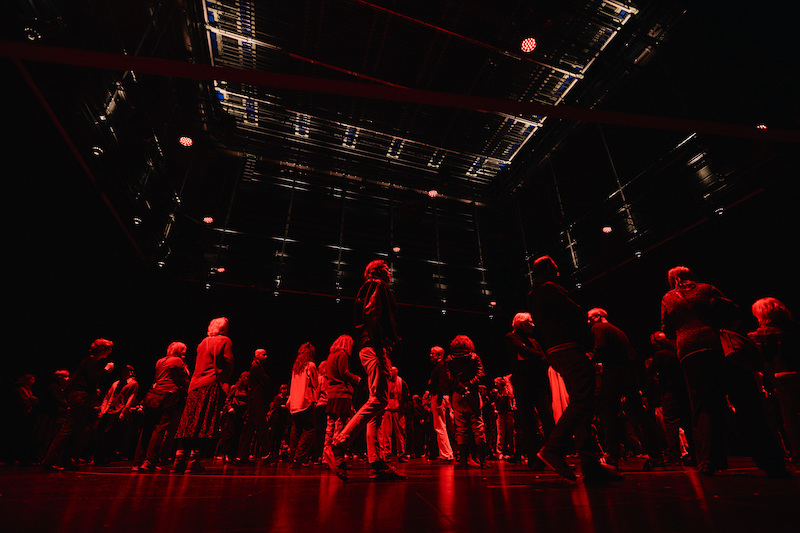

‘Finale,’ 2025 at MaerzMusik 2025, Haus der Berliner Festspiele // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

‘Finale,’ co-curated by composer Wojtek Blecharz and festival director Kamila Metwaly, let go of dramatic staging to invite the audience directly onto the stage and lead them through a series of musical performances. Space was activated through simple spotlights, sometimes surround sound, and at other times localized actions. There were moments when musicians appeared in the audience’s role, playing brass instruments between the chairs, while at another point two walls opened to reveal stages within stages, inviting the listeners to stand beside the performers and even examine the exhibited scores. At one point, two panels from the stage’s floor were removed to offer a glimpse of the basement, into which people were also invited in smaller groups. The pace, sonic overlapping and choreography of performances and spaces never prompted the aimless loitering that burdened ‘The Urban Tale of a Hippo.’ Instead, audience movement was effortlessly contained, coaxed into different sensations—again including a “silent” piece with ear plugs, but this time performed on participants by gloved musicians—that culminated in an audience rendition of Pauline Oliveros’ ‘Tuning Meditation.’ Everyone was instructed to hum a note of their choosing, and in the next breath, hum a note that they heard from others. This process continued until the audience organically stopped, the lights switched on and the musicians appeared standing in the theater hall, there where the audience normally sits. Roles reversed, a standing ovation ensued, and blinking from the bright spotlights shining in our faces, some of us probably wondered, “Did we all hear the same thing? And who was the one performing?”