by Diane Barbé // Apr. 4, 2025

This article is part of our feature topic Public.

The Casino for Social Medicine is an experimental, collective and anti-capitalist bar and café that recently opened its doors in a former Spielhalle at Sonnenallee 100, in Berlin-Neukölln. Since its launch in October, it has been run by a dozen volunteers, self-described as a “porous group of anti-colonial migrants, activists, radical librarians, writers, anarchist landscapers, facilitators, grassroots organizers, artists and recovering individualists,” who come together to sustain the Casino as a third space, oscillating between a coffee house, a clinic for collectivist experiences and a mutual aid experiment.

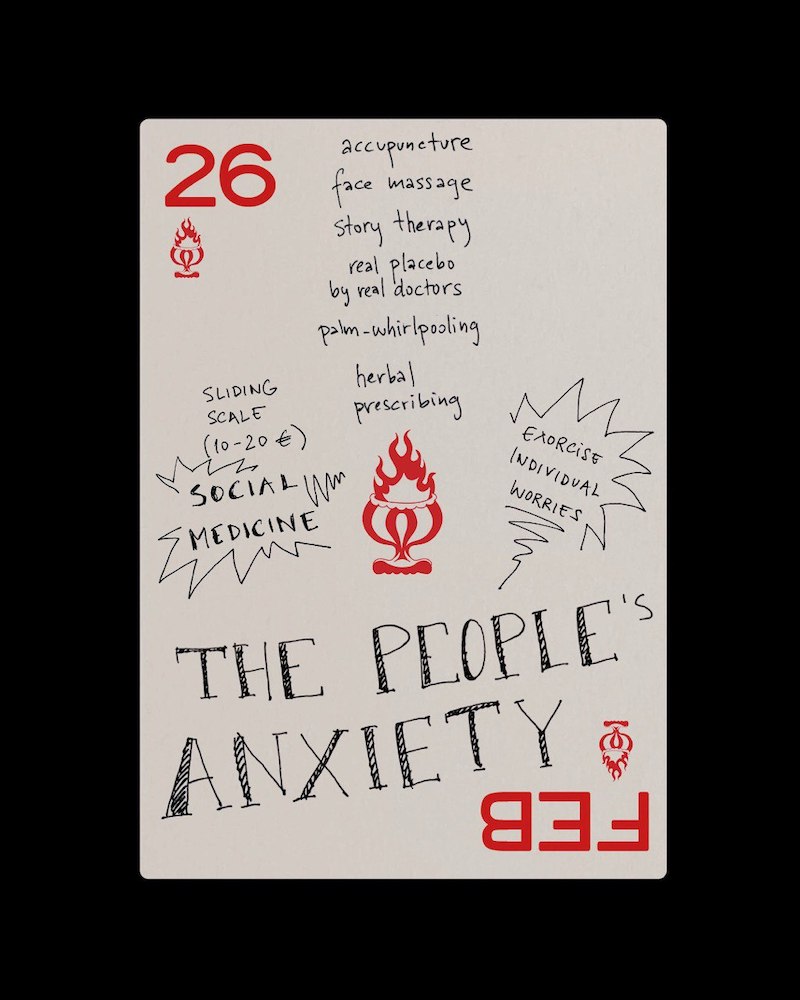

One of the anchoring points of the Casino is the Hologram, a social technology that proposes a protocol for learning to give and receive care between peers, and the Casino acts as a material space that facilitates this notion of social medicine, aiming to provide some of the skills and relationships needed for surviving in the capitalist paradigm and for imagining a post-capitalist future. And, indeed, the weekly program of the Casino is radical and diverse, based on the wider community’s proposals that include free help desks, workshops, concerts and talks. For example, one can come to ask questions about bureaucracy, get translation services or simply feel supported in a paperwork task at the bi-weekly German-Arabic-English help desk. On another day, the Casino will host a group discussion about the Kurdish Women’s Movement, or about Martyrdom and the Palestinian Tradition. Other events include weekly NADA acupuncture sessions, open talks about magic, astrology consultations or monthly a “Repair Cafe.” This week, Casino is hosting ‘ASMR,’ the Anarchist School for Social Medicine from April 2nd to 5th. During those four days, the space becomes a clinic, offering free high quality healthcare from herbalists, layman massage practitioners, scoliosis experimental specialists, acupuncturists and more. We spoke to Casino initiators Magdalena Jadwiga Härtelova and Cassie Thornton about the space and its implications for public life.

Angel B. H.’s ‘All Hookers Go to Heaven’ book launch event and discussion on sex worker’s right // Photo by Dylan Spencer-Davidson

DB: How was the Casino for Social Medicine created? What were some challenges that you faced in the process?

Cassie Thornton: When the previous bar stopped operating here, the owner invited us to make a proposition. None of us had run a business before nor did we have money, and the rent is pretty expensive. But we started meeting every week. At the beginning, we were just four people who had worked together on the Holographic School for Social Medicine, which ran for three months here in 2023. We kept asking around for people who would be interested in opening an experimental cafe, and one by one, the group got bigger.

Magdalena Jadwiga Härtelova: It started to become real when someone gave us the money for the deposit, and for the first round of drinks. Overall, there are many people involved, because everything has to run on volunteer work, which hopefully will change. Everyone does what they can. There is someone who helps us with finances; one person plants stuff by the tree in front of the cafe. Another reason we were able to open is because we were gifted a lot of equipment from the cultural center Oyoun, when they were forced to close—the fridges and the coffee machine, which is called Luna. We were all there when it got shut down, and that was really because of their programming. A lot of us kind of expect that at some point we will also have legal trouble.

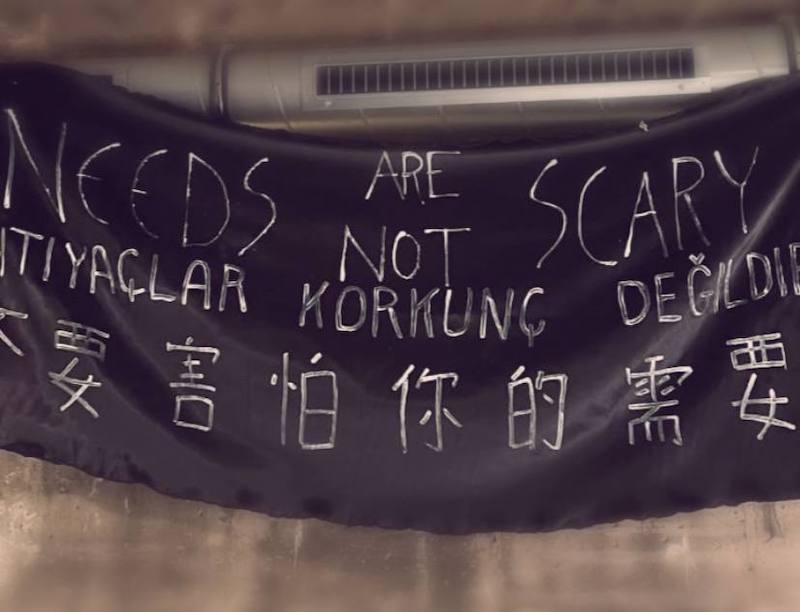

Banner at Casino entrance // Photo by M J Hartelova

DB: What kinds of events do you host at the Casino? Do you curate the program, or have particular ways of shaping the space?

MJH: We’ve thought a lot about how we approach people and how we structure the space. Through the Hologram, we learned a bunch of things, especially how to hold space and facilitate a room where eventually people can enter in really deep conversations with strangers. It’s subtle and precise. It’s not just about saying “we are accepting, let’s talk to strangers.”

For instance, the bartenders here have a little bio printed out at the bar, which says their name, what languages they speak, what they like to talk about, what they can help you with and also what they need. This really changes the nature of being a bartender: you are here as a human, and you immediately have much more interesting conversations. And many of the bartenders had to make another bio because all their listed needs got met just through having that bio on display. We have a banner at the front that says: “Needs are not scary.” But they require a kind of social gluing, or social prescribing, as it’s called by the NHS in the UK. So one of the functions of the Casino is that it is a connecting spot, a place where people can come and have their needs met between each other. This is why we call it a clinic. Another example is that we host help desks where people offer skills they have, for instance someone who speaks German, Arabic and English comes in for a couple of hours to help out with bureaucracy. People are just so happy to actually talk to someone. We’ve had a help desk about top surgery, another one about digital security.

Bartender bio, Magda // Photo by Chris Harris

DB: I was recently reading ‘The Tyranny of Reality’ by the journalist and author Mona Chollet, where she describes how advertisements insinuate that objects will fill our needs: if you have this product, then you won’t need anybody. And that is celebrated, as if it were an accomplishment not to need anybody. How does that resonate with the Casino?

CT: Since we opened, we have been serving Sternies for 2 Euros, and that is so special for people, like going back to a time when Berlin wasn’t about financial survival and there was much more of a collectivist culture, because not everybody had to get a tech job on the side. There is something in acknowledging that we really share a struggle to survive, to keep our heads on and pay the rent in the middle of the apocalypse. I also think about two events that we hosted, one last week about martyrdom in Palestine and one about Islam and anarchism. When we involve people who are organizing around Palestine, from Palestine, we’re able to talk about a different way of thinking about materialism. It helps us see that European and German cultures are very materialistic, but there are other options for ways to live, and other reasons to live.

Event poster // Copyright Dylan Spencer-Davidson

DB: You’ve said that the “event recipe” you advocate for has a political dimension, an aesthetic element and a practical application. Are these parts just complementary? Are they necessary, in the sense that an artistic practice can never be really apolitical?

MJH: Well, a lot of art still pretends to be apolitical, of course, but we try to encourage that experiences like lectures or concerts here, which typically are taken in more passively, should be paired with something practical: a skill-share, a story, doing something with your hands. In a way, it funnels in people who are interested in activism but live mostly individualistically and then presents them with real possibilities. For instance, we had one event with a rapper who has a lot of really engaged lyrics, and most people came to listen to the rapper, but alongside that we had also programmed someone who was giving advice on how to protect yourself at demos, what to do if you get pepper-sprayed, how to de-arrest somebody—really practical tips. And this opened a kind of possibility for everyone to feel like they can actually go and do things.

CT: We’re really insisting here that there is something more that’s possible between art and activism. We don’t know what it is, but it’s definitely not about an individual artist, and it’s not about repeating what we know in activism. Almost every event feels like we’re learning hard about both art and activism, about what’s possible and what’s real.

MJH: Cassie and I are publishing a book for culture workers in the Apocalypse, called ‘It’s Too Late, Do It Anyway’ (coming out with Thick Press in September 2025, with pre-orders starting in May). One of the big theses is that in the art world, we’ve mixed up talking and doing. We think that if we have a symposium about care, we’re caring, or if we do an exhibition about interspecies dialogue, we’re having an interspecies dialogue. But those things are actually different. And it’s not about raising awareness anymore. We all know, everybody knows, the internet is here: everybody has known for a really long time. It’s not a problem of knowing but a problem of doing: where do I start? How do I change when I know I need to change? How do I get myself unstuck?

Additional Info

casinoooo.org

Support the Casino: ko-fi.com/casinoforsocialmedicine