by Marta Jecu // Apr. 25, 2012

Part two of a two-part interview. Click here for part 1.

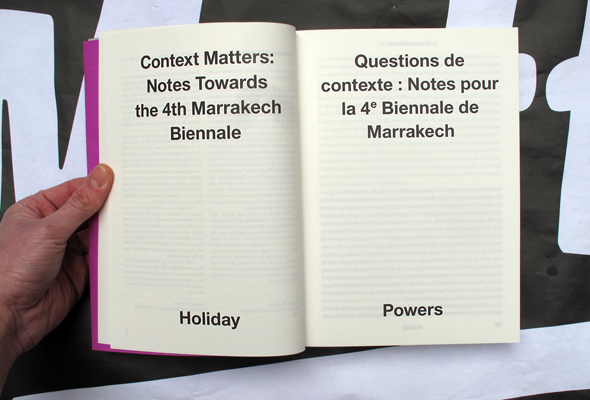

The Biennale’s accompanying volume Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context, edited by the curators, is indeed a collection of contexts: the cautiously woven and entangled layers create a rich cocoon, however the larva is absent. The book constructs a scaffold of mainly theoretical articles, which confront a post-colonial treatment of “the subject.” This subject, Morocco, is treated either over an expanded geographical notion, or through cultural appurtenance, which aims to integrate, represent, or situate Morocco (whereas these distinctions remain blurred). These wider frames of representation are “The South”, “Arab art”, “African art”, and “Africanity,” and appear in the majority of the articles, delineating an elaborated, but rather out-of-context history of contemporary art in Istanbul by Beral Madra. Going through the book, the presence of a consistent analysis of what Moroccan art has been in the past century, which is necessary to knowingly situating it now, is missed.

Holiday Powers: Context Matters, Higher Atlas/Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context // Edited by Carson Chan and Nadim Samman // Design by John McCusker and Sara Hartman // Published by Sternberg Press, 2012 // Courtesy of Motto Distribution

In Anthony Gardner’s text, the broad notion of the “The South”, to which Maghreb, along with South America, Australia, Africa and the Arab Countries all belong, for the author means both a geographical region as well as a common history of colonialism – and he is referring both to the early modern colonialism reading and the more recent neoliberal one. Analyzing the biennales in these regions, he not only concludes that their role has mainly been to re-imagine the regional, but also asserts without prior preparation, that these “peripheral” exhibitions are of a socialist nature (Anthony Gardner, “Biennales on the Edge.” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context, pg. 104).

Holiday Powers: Context Matters, Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context // Edited by Carson Chan and Nadim Samman // Design by John McCusker and Sara Hartman // Published by Sternberg Press, 2012 // Courtesy of Motto Distribution

Katarzyna Pieprzak and Jessica Winegar , in their article “Africa North, South and In Between,” and Alice Planel in “Traveling back to Ourselves,” discuss the relation between art in North Africa and in Africa’s more southern regions: they each respectively situate Moroccan art in the Maghrebian art context. Veronique Rieffel talks about “Arab” art, but avoids the religious elements at play (Rieffel, “Contemporary Arab Art,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context) and Simon Njami and Kerryn Greenberg discuss at length art on the African continent (Njami, “The City in Blue,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context; Greenberg, “The City as Site: Building an Audience for Contemporary Art in Africa,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context). The articles are constructed around post-colonial academical discourse, which is applied to the different cultural/geographical “zones” of discussion. Morocco itself appears in most articles only peripherally and is mostly treated through analogies (especially to other cultural spaces). The questions that emerge are indeed pertaining to a larger investigation: on what basis can we construct analogies between the art of Istanbul and that of Marrakech, the art of Central Africa and that of Morocco? And is it not precisely such an analogy that perpetuates a discourse that fails by not involving the direct participation of its subject?

In this sense, the article that Katarzyna Pieprzak offers (“Taking Moroccan Art to the Streets,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context) is a very interesting perspective through which Moroccan artistic reality can be followed in the close-up: through public art, during a specific period of its recent past. In a dense text with historical sources and archive material (quotes from journal news, commentator’s quotes and archival interviews with the audience of the works) the author gives a rather anthropological and, simultaneously, art-historical insight into attempts of the 1970s to move art into the public realm in Morocco. The negotiations between the artistic and intellectual elite, the audience from the street and the media bring issues of urban planning, social relevance and authenticity (all specific to that period) to the forefront of discussion. Pieprzak reconnects these ideas to contemporary projects like the Casablanca art collective La Source du Lion, who are interested in the participatory recuperation of the city’s past, as well as the communitarian memory that constructs contemporary culture.

Also in the first article of the volume (“Context Matters,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context), Holiday Powers mentions and describes some initiatives, projects and contemporary works, including L’Appartement 22, whose initiator, Abdellah Karroum, also curated the last edition of the Marrakech Biennale as well as the Moroccan Pavilion at the last year’s 54th Venice Biennale (conceived as a working laboratory to accompany the Tahrir Events).

Yto Barrada: A modest proposal, Exhibition view at L’appartement 22, Curated by Abdellah Karroum, 2010 // Photo by A.K. Courtesy L’appartement 22, Rabat

In their articles included in the volume, the two curators trace the concept of “internationalization,” with which the Biennale as a whole attempts to engage. In his text “The Shifting Site,” Nadim Samman, departs from the transcending geography that Higher Atlas, the exhibition’s title, suggests. He describes the location of the works (from Morocco at-large to the Theatre Royal as main exhibition site) as “a point of junction.” “The various interventions on-site, about site, around and above it map an expanded field of ‘location’ – they are a series of connections to a node, shooting off in multiple directions towards other spaces, both physical and virtual…it performs site-hood as a point of constellation, figuring the theatre as a super-node in a multi-dimensional web of connected physical and discursive locations. Thusly the works in the show textualize space and spatialize discourse.” Here Samman refers to a theoretical fundamental of Gestalt psychology, namely the shifting perception of figure and ground, which flip into each other, and where the viewer needs the ability to “see” by switching back and forth. “Visitors can consider site-hood (and cultural identity) as a series of connections:” Samman’s argument is finally that only such a view on the site and its values can avoid an essentialist approach to it, that would otherwise have to stick to an ossified tradition. He states that rejecting the fact that Moroccan culture is a mix of influences, would be an Arab-centric approach. And still, is it not an in-depth and applied analysis of the specificity (with its cultural elements and roots, which can be both of religious or laic nature) that allows us to view the super-node of mixed influences, without getting stuck into orientalist images or “dubious myths of origin.”? (Samman, “The Shifting Site,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context).

In his article “Let Me Entertain You: A Consideration of Context and Audience in Curating the 4th Marrakech Biennale,” Carson Chan states the goal of formulating a curatorial proposal that does not only address the local elites (as contemporary Moroccan art currently does). The Biennale artists chosen are context-sensitive, master a universality in their way of communicating, and privilege primary experience of the senses (Chan, “Let Me Entertain You: Consideration of Context and Audience in Curating the 4th Marrakech Biennale,” Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context). I consider the perspective forwarded by Chan interesting: his renouncing of the neocolonial grid interpretation facing a Biennale (which is founded with foreign money and works mainly with foreign artists) as accusing a-priori its founders and curators of reproducing historic patterns of power, to not only be simplistic, but also unproductive. In a much-quoted statement from an article in ARTINFO Berlin, he affirms that “it’s been what, half a century, so to say, that anyone going to do a project there, is a post-colonial gesture – is kind of like beating an old horse” (Alexander Forbes, December 12, 2011). In the same interview Chan argues that it is more important to see “how a post-colonial identity has affected people in Morocco.” In his article included in the catalogue, Chan refers to the time of political shift when the institution-museum in Morocco turned from being a container of colonial ideology into an expression of national ideals, with its stereotypical content, and where traditional art “had to be saved.” These are indeed layers worth investigating, rather than sticking to an oversimplified rejection of capital and value importation, in the name of of a post-colonial paradigm.

Still, beyond the awareness of the complexity of these issues regarding the artistic reality in Morocco that Chan’s statements raises, the Biennale itself does not seem to work directly with a reality made of mixed or shifting local identities, or with the link between Islamic tradition and Western modernity. For example the Abstract Expressionistic tradition in painting that Chan comments on, and that is a reality in university education, is not dealt with or analyzed throughout the exhibition. Also, not only the supposedly Western spectator that Chan mentions, but also the Moroccan non-elite spectator can be part of the Biennale: not as a casual viewer, but also as a carrier of a culture and participant, with his personal experience (the “discrete and non-transferable marker of selfhood” that Chan mentioned as being the anti-dynastic intellectual of Edward Said (Alexander Forbes,”Marrakech Biennale Curator Carson Chan on How the Arab Spring Has Influenced Exhibition-Making,” ARTINFO BERLIN, December 12, 2011)

The exhibition displays the implication of traditional Moroccan elements of crafts, which is quite ambiguous: it represents a link to the context, but it reminds one precisely of that “saving“ of traditional values, what Chan was referring in the context of post-colonial national discourse. It leaves the question open about which layers of local culture can be appropriated and which can be assimilated in an artistic quest. A purposeful “borrowing” of “traditional” elements, rather than their more profound circumstances of emergence and historic layers, can create a hierarchical separation between them and “contemporary” forms, which are supposed to re-valorize them and give them an extra meaning. Going back to the nightly scenes in Djemma el Fnaa, for example, one can ask if this is a display of traditional art or a contemporary reality with all its political, social and individual layers. The Biennale can be treated as a temporary part of this contemporary reality, and after all, the Biennale is intended to be “a space of entertainment, of amusement…” (ibid).

The work of Roger Hiorns offers from this point of view a bright solution: he commissions a group of Moroccan musicians to perform at different locations of the Biennale. They perform their own music in formations that they prefer, while never having direct contact with the artist who merely sent them his instructions. Their powerful presence during the Biennale’s events de-contextualizes the other works, shaking the borders between them and the art of the streets. They offer a new reference and frames of interpretation, including a mutual mis-interpretation of “the other” in the substance of the work. The works seem transformed and gain a new dimension by the vital presence and performance of the musicians at their side, like the monument of Aleksandra Domanović, at which the group made its last show. In response to the curators’ questions regarding the project, Hiorns simply said, “it was a remoteness established by making a small request, towards some result, never to anticipate, or interfere in the gap established between the line in my request to the curator and my willful misunderstanding of the choir” (Higher Atlas / Au-Dela de l’Atlas: The Marrakech Biennale (4) in Context).

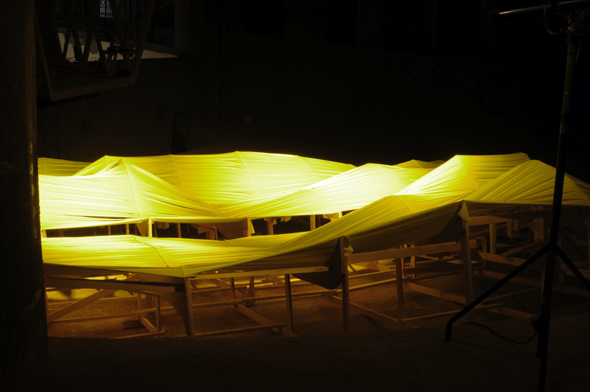

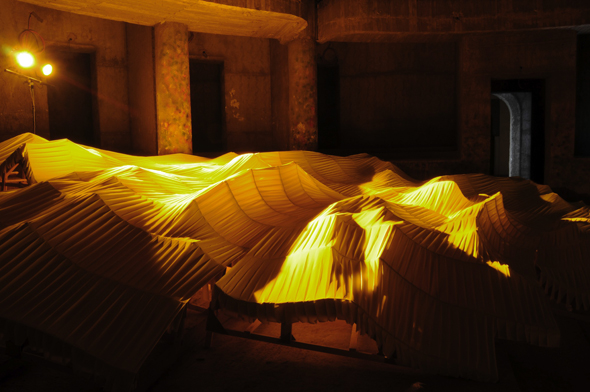

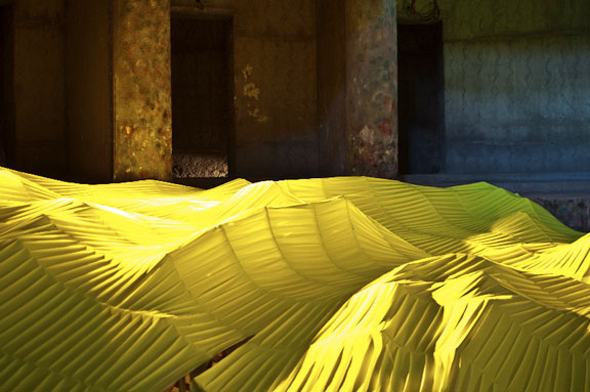

Also based on a conceptual approach, the work of Sinta Werner is equally lacking ambiguity. Her metaphysical search for the natural form of a dune involves substitution of digital-analogue models of representation and the intrinsic dimension of time and movement, that makes a dune exist. Sitting down with her gave a deeper understanding of her focus and proccess:

Marta Jecu: You were telling me yesterday that you started with a model, that afterwards you wanted to translate back again. Can you tell me about this process in a few words?

Sinta Werner: The idea came from making a generic form: a dune set that comes from the nature but that is a perfect form, made by coordinating the winds and the dunes. The dunes I animated in a program called Cinema 4D and I transformed it back into something physical.

MJ: You animated the dunes, brought them into movement and than brought them back into a still?

SW: Yes, dunes in general are a still of movement, that is also what interested me a lot about them. Cinema 4D is like a 3D animation program; it is 3D + time. This dune is a moving form that has been made, created by someone. It is a still of this moving form. I transferred it back into the real environment by setting up a rule, a concept for myself: to cut it into sections and then to combine the sections by the neon colored stripes, which is like a grid pattern that created these abstracted dunes. It was the idea of the repetition and the idea of the 3D modeling of something that has the ability of endless repetition – and turning it from the digital to the analogue again. I also wanted to bring up the question of how the 3D modeling is creating and influencing our daily (urban) environment, with this repeatability. It was interesting being completely immersed in the process without having the overview and than going up in the theater and seeing how the form would actually evolve.

MJ: Why did you choose this color of the stripes?

SW: I wanted the color to look quite synthetic, like a non-color. This yellow neon is something that is used for signs in the streets. It is something very aggressive and artificial. I wanted to put a contrast to the natural forms that inspired me.

Luca Pozzi creates systems and infuses them with physical forces that materials posses. “The Star Platform,” his work in the Biennale, produces levitating particles with electro-magnetic fields, that bring an universal, archetypal symbol into “acting.” His clearly articulated, conceptual work, transmits a certain serenity, while searching for new ways of knowledge production and transmission.

Luca Pozzi: The Star Platform, 2012 // Electro-magnetic levitation field (simerlab), luminescent sponges, polished aluminum, wood, neon lights // Photo courtesy of L. Pozzi and Federico Luger Gallery

In speaking with Pozzi, he talked more about his relationship with Marrakech:

Marta Jecu: Tell me please some words on your residency time in Marrakech.

Luca Pozzi: I spent ten days in Marrakech, one day as a stupid and naive western tourist, three as a carpenter, two as an electrician and another day as a painter, I spent 25 minutes as a muslim and only one second as a flutist. For the rest of the time I was a walker and in the night time a researcher between researchers.

MJ: How did you connect to the place?

LP: Always with love.

Luca Pozzi: The Star Platform, 2012 // Electro-magnetic levitation field (simerlab), luminescent sponges, polished aluminum, wood, neon lights // Photo courtesy of L. Pozzi and Federico Luger Gallery

MJ: What interested you most in the culture you encountered in Marrakech?

LP: The sense of community and the respect of rituals. A taxi driver one day told me: If you don’t pray at the right time and in the right place it is like not praying at all. Sometimes the respect for the grammar of the rules is a way to built, in another layer of consciousness, the grammar of the faith: its the source of our determination. I respect this approach.

Elín Hansdóttir: Construction of Mud Brick Spiral, 2012, Moroccan mud bricks and mirrors // Photo courtesy of the artist and i8 Gallery

MJ: What precisely did you research here?

LP: I am always looking for the same thing everywhere: the connective structure.

Elín Hansdóttir: Construction of Mud Brick Spiral, 2012, Moroccan mud bricks and mirrors // Photo courtesy of the artist and i8 Gallery

MJ: How was your response to the time spent there, either on a personal experiential level or in your work?

LP: All the artists involved in this ambitious project were tuned on a certain frequency, the selection of curators was very precise, even if sometimes their criteria seem very open or random, they aren’t. This fact was actually very helpful in sharing approaches in a very direct way. So in a personal experiential level, but also concerning the work, I had the feeling that we are a sort of Augmented Art generation. To land in this new territory, far from the standard art-system was a way to augment my references and augment the information of the art-works and not to colonize a new public.

Elín Hansdóttir: Construction of Mud Brick Spiral, 2012, Moroccan mud bricks and mirrors // Photo courtesy of the artist and i8 Gallery

A truly site-specific work is that of Elín Hansdóttir, constructed in the village of Tassoultante, during her residency at Dar Al-Ma’mûn. With the involvement of local masons, and the local community that participated constantly during the process, she has built a spiral construction in Berber brick and mirror.

Elín Hansdóttir: Construction of Mud Brick Spiral, 2012, Moroccan mud bricks and mirrors // Photo courtesy of the artist and i8 Gallery

Elín Hansdóttir: I got very interested in the traditional Berber building technique, the mud bricks,” says Handottir. “I was fascinated by the fact that unlike us in the West, they almost use no tools during construction, it’s mainly manpower and imagination. Furthermore, it is interesting that they use the soil on the actual construction site to produce the building material. This results in whole villages almost seeming to mutate out of the landscape. These are ideas that I very much relate to in the sense that an element of the actual site is used (sometimes even changed or altered) to produce a different context…context is something that is very important to me when I start working on projects, so obviously I had done some research on islamic architecture and techniques, for example some of the arabesques, which incorporate a kind of infinite reproduction of their own image within a system. But of course living around a very distinct kind of architecture of the mud bricks made me research the production techniques of the mud bricks. So I guess one thing lead to another, like so many times before.

Part two of a two-part interview. Click here for part 1.

Biennale Info

marrakechbiennale.org

Feb. 29—June 3, 2012

higheratlas.org

Feb. 29—June 3, 2012

Writer Info

Marta Jecu is presently a researcher at CICANT Institute in Lisbon, and has contributed for various magazines, including E-Flux, Kaleidoscope, Journal of Curatorial Studies, Idea Arta+ Societate, and various critical books, such as Visual Studies, Ed. Jim Elkins.