Article and photos by Jeni Fulton in Berlin; Tuesday, June 12, 2012

With dOCUMENTA (13), Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has created an exhibition which points to the paradox at the heart of contemporary art. As she puts in her opening statement: “the riddle of art is that we don’t know what it is, until it no longer is what it was,” resulting in an exhibition with no central concept. Bakargiev neither wants to contribute towards “cognitive capitalism” via a footnote-studded text, nor have artists illustrate a curatorial theme: instead, she admonishes us to relinquish our anthropocentric perspective and rejoice in a neo-Romantic attempt to unify nature und humanity into a glorious Whole.

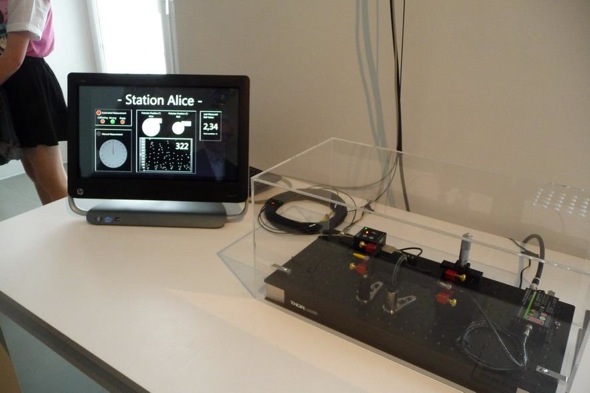

Ryan Gander fills five out of nine otherwise bare rooms on the Fridericianum’s ground floor with a cool breeze, and in an adjoining room, Ceal Floyer’s sound installation intones “I just keep on trying/til I get it right” – there is no end goal, only endless permutations which edge us nearer to understanding (but understanding what?). The concept of no concept is carried further in physicist Anton Zeilinger experiments showing the wave/particle duality of photons in a classical two-slit experiment, metaphorically emphasising the decentred notion of art in operation. Bakargiev’s show can give the impression of being the world’s largest interdisciplinary symposium: performance art sits beside particle physics and canine sculpture gardens, all grouped around the concepts of theatre, being under siege, and anticipation and withdrawal.

Bemused media looking at the only tangible piece on the ground floor, Kai Althoff’s refusal letter to Carolyn Christov- Bakargiev. It wasn’t meant to be art.

Bemused media looking at the only tangible piece on the ground floor, Kai Althoff’s refusal letter to Carolyn Christov- Bakargiev. It wasn’t meant to be art.

This results in a show that feels surprisingly light and playful. The dreaded didactic panel, a German museum favourite used to evince metaphysical banalities and obvious descriptions is used sparingly, and only when the work requires it. In fact, the entire exhibition is sparse on information: the catalogue only holds brief descriptions of the pieces and artists involved, eschewing lengthy explanatory essays – these are part of the 100 days, 100 essays series of books. In the Fridericianum, Bakargiev has installed a “brain”, essentially a panoply of ideas which guided the exhibition, acting in place of a concept. These range from 3500 year-old “Bactrian Princesses”, over arte povera artist Guiseppe Penone’s river stone Essere fiume 6, to Man Ray’s eye metronomes, to photographs of Lee Miller in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub. She has included the Egyptian artist Ahmed Basiony’s mobile phone videos taken just before he was shot in Tahrir Square in Cairo, and semi-destroyed artefacts from the National Museum in Beirut.

Thomas Bayrle’s anthropomorphic machines

Thomas Bayrle’s anthropomorphic machines

When her idea of decentredness works as with Mario Garcia Torres exploration of Boettis One Hotel in Kabul (1972-1978), and the Gander, it is a strong illustration of the current feeling of contemporary art – that nothing is certain, that there are few or no limits, and that ultimately, the autonomy of art itself is in question. Where she fails, she fails spectacularly, as in the laboured juxtaposition of Salvador Dali’s disintegrating figures and the immunologist Alexander Tarakhovsky’s DNA test tubes and centrifuges. Tarakhovsky works in the field of epigenetics, studying the impact of external influences on genome expression. Presumably Dali’s distressed figures are intended as a warning against the pathogens of “complacency” and “dogma” – a collapse into specious nominalism.

While much of the work reflects on the deleterious impact of war on culture, with remnants of Bamyian Buddhas being shown alongside the remnants of books from a Kassel library bombed during World War II (Michael Rakowitz, What Dust Will Rise), the key achievement here is that it is strong enough to withstand falling into the miasma of pathos, and simplistic enough to give peace a chance messaging that so often besets this type of work. Francis Alys’ film Reel/Unreel (available on the documenta website) is, on first sight, a simple sequence of two boys playing chase with two 35 mm film cartridges through the streets of Kabul. Tap a little deeper, and it is a homage to the members of the Kabul film institute, who, by handing out film prints (and not the original negatives) to the Taliban saved the stock from destruction, and to art’s current focus on obsolete media.

Anton Zeilinger’s station alice

Anton Zeilinger’s station alice

In general, the exhibition veers wildly from a focus on its above core themes, and its avowed anti-conceptualism. While the latter tendency (possibly encapsulated by the “theatre” category) lulls the viewer into a sense of almost childlike wonder and delight, the former serves as counterpoint – for instance, when one comes face to face with Kader Attia’s photographs of WW1 facial injuries which he combines with broken African statues to astonishing effect.

The strongest positions are contained in the Fridericianum, and while Bakargiev has included a previously unmatched number of off-sites (including a bank vault, a bunker, a hotel, a parking garage and a derelict house) in addition to the Documenta stalwarts Hauptbahnhof, Documenta-Halle and the Karlsaue park, these are hit-and-miss in terms of their incorporation into the exhibition as whole. Signposting and orientation are occasionally inaccurate, and given the nature of some pieces (Jimmie Durham’s cabinet at the Ottoneum, for example), or Gander’s reader in the Orangerie café, in danger of vanishing into their surroundings altogether. The Documenta-halle includes traditional media: numerous drawings by Gustav Metzger, and large-scale Julie Mehretus alongside Thomas Bayerle’s man-machines. It all feels a bit epic and spectacularist.

Haegue Yang, blinds opening and closing (only a little hommage to Martin Creed)

Haegue Yang, blinds opening and closing (only a little hommage to Martin Creed)

Strong off-sites included Theaster Gates occupation and restitution of the historic Huguenot house, restored with material from Chicago. Gates had included videos and installations focusing on the 1960’s civil rights movement, and included performances by Mississippi musicians. His workers lived and cooked onsite, providing for a more interesting relational aesthetics experience. The sound art pieces were some of the strongest showings at the Documenta (13), ranging from Tino Sehgals performance (20 a cappella singers in a blacked-out hotel room, surrounding the viewers in a wall of vocals) to Susan Philipsz’ haunting cello and violin duo which drifted out across the industrial Hauptbahnhof site. A highlight was Cevdet Erek’s Room of Rhythms, a site-specific installation in an empty shop-floor in the C & A clothing store. 60 bpm bass and high-hats drifted through the space, echoing the passage of time (and the number of windows), and appropriated (and distorted) department store signs littered the room.

The vast range of media, artists, themes and references provide for an uneven, but ultimately strong showing. The concept of no concept allows the viewer sufficient space to view the works sans ideological glasses: while Bakargiev may want to emancipate strawberries, she draws the line at emancipating art from the museum/the white cube/and so on as previous Documentas have attempted to do. The inclusion of what basically amounts to the entire city of Kassel (and Kabul, and Cairo, and Banff) forms an elegant Gesamtkunstwerk for the viewer to wander through, an augmented city where nothing is as it seems, and where little guidance is provided as to what should be thought.

__________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

dOCUMENTA(13)

Exhibition: Jun. 09 – Sep. 16, 2012

Opening Hours: daily from 10am to 8pm

Friedrichsplatz 18, Kassel (click here for map)

___________________________________________________________________________________

Jeni Fulton is a writer focussing in and on the international Berlin art scene. She is currently working on her PhD thesis in contemporary art theory. Having taken her MA in Philosophy at the University of Cambridge, she now lives and works in Berlin.