by Elizabeth Feder, photos by Elizabeth Skadden // Aug. 8, 2012

When exploring Kandis Williams’ studio, one is struck by the incongruous balance between the pensive quality of her collages, drawings, and prints, and the dynamic range of projects she has undertaken for the coming months. Williams’ work, while marked by her black and white, large-scale collages, branches out to encompass mediums such as performance art and choreography, print and publication, and even arts education. But what ties Williams’s projects together is her confrontation of questions of identity, place, race, and use of the human body.

One word that sat with me as Williams walked me through her studio in Neukölln was urgency. And while she used the term in the context of her media-choice and methodology, it aptly encapsulates the immediacy of her process and ravenous energy of the pieces that fill her workspace. Not minutes after we met, she unraveled two new prints to reveal a collision of disparate bodies. The fighting figures varied in size, resolution, and color saturation, but the gravity of their friction was even more explicit because of the visual contrast. The languages of altercation is increasingly influential in Williams’ work, especially after her strenuous experience setting up and maintaining a camp for arts education in New Orleans last summer. The friction that she faced between the different tiers of power who claimed control of the camp’s site, as well as from within the community itself, inspired a narrative that looks at the behaviorology of violence: her most recent works looks at a choreography of confrontation, even the potential artistry in altercation. Bodies transform, languages morph, and the fight becomes a figure unto itself.

Williams began developing this exploration at New Capital Projects in Chicago, where she was their first artist in residence, in August and September of 2011. There she not only furthered a visual analysis of different types of altercations, but she also engaged the inherent condition of spectacle that buttresses the overall subject-matter. Williams focused specifically on what she describes as a Dziga Vertov “kino-eye” view, where cellphones, point-and-shoot cameras, and the internet-generated-user video community have sustained a digital archive of deliciously random events, many of which are fights. The visual atmosphere of her newest prints call into question this aesthetics of accessibility, notably the textures of pixelation (the videos have gone viral partly because of their pulp content, and partly because of their low-resolution ease of dispersal). Williams is harnessing this visual language in an almost painterly way and, when taking stock of her previous work, it fits conceptually in her process.

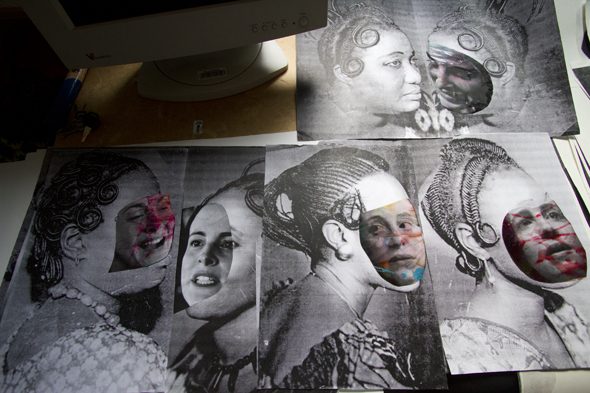

Many of the pieces that currently blanket Williams’ studio are massive collages that investigate specific found images and the stories imbedded within them. Certain visual motifs recur often in Williams’ work: shrieking, mournful mouths, complex French-African braids, and, now, fighting figures, are familiar elements in a variety of compositions. The result is a thematically and visually connected oeuvre, but it is also indicative of creative obsession-turned-meditation. Williams has been using some of these images in her work for years, and the evidence of this dominates her studio’s atmosphere. Her main workspace is full of prints, cut outs, preliminary collages, and thick sketchbooks that attest to the dedication she has given to these striking visuals. “I carry around these suitcases full of images wherever I go,” Williams notes, “…for instance, these [photocopies] are from Broken Blossoms, the 1919 D.W. Griffith silent film, and these are some images of black hairstyles from the 1960’s in France. I’ve been carrying these around for 6 years now.” This meditation is a process that, for Williams, allows for a kind of personal catharsis. And when she first came upon the fight videos, she decided that she would stay with it for a least one year.

Hers is a commitment to content that is a refreshing assault on the contemporary tendency to move ferociously from one stimulus to another. And in this intense focus, she has carried many of these images through exciting iterations: they’ve been drawn from, cut up and recomposed in collage and other forms, they’ve been inverted, and they’ve been magnified. When asked what draws her to a particular image, Williams notes that it can be a textual quality, where the image clearly has a story, or it can be something totally physical, as was with the 1960’s French-African hairstyles. The bright shine and complex geometries of the braids immediately attracted Williams, but the way these images fit within a kind of anthropological idea of black identity is just as critical. The aesthetics of global African culture in general, and African-American culture in particular, is legible in much of Williams’ work. More specifically, there is a larger cultural act of aestheticizing that Williams has identified as a vital, defining part of the African-American identity. In her reference to Zora Neale Hurston’s essay on what Hurston calls the “quintessential parts of African-American culture,” Williams connects to the the idea that one “aestheticizes everything.” From clothing to hair, housewares to automobiles, Williams recognizes that this tradition can be observed from the outside as a negative “other,” however she looks at it as a tradition from long line of people who have an aesthetic legacy.

For her participation in the recent One Day at a Time group show at Peres Projects in Berlin, Williams exhibited an untitled collage composed of repeating, interwoven arms that created an eerie human textile. Here, aestheticizing the human body is pushed to an even more intense extreme, where the figure is then transformed into a coveted commodity through acts of exacting ownership, mutilation, and sacrifice. In this series of five “Untitled” works, Williams references the violence against black albinos in Tanzania: a violence that is dually rooted in racial prejudice and mystical awe. For Williams, there is a fascinating transubstantiation happening through the possession of these bodies: the form of the “other” is transformed into a commodifiable, spiritual object through murderous, dehumanizing acts. And while there is inarguable horror in the desecration of these bodies as to to transfer power from one social group to another, Williams uses the image of the severed albino’s arm in order to construct a different kind of talisman. The collage weaves together a new body, where the image that once represented devastation and domination is transformed through Williams’ redefinition of its physicality.

Williams’ use of collage to explore this narrative is both beautifully appropriate and somewhat horrifying. In the context of these pieces, collage is an emphatically violent act in and of itself, where the source images are manipulated through dissection, de-contextualization, and recomposition. This “Untitled” series (all made in Chicago at New Capital Projects) utilizes the image of static figures in order to create rich new fabrics that ultimately supersede the loaded meaning of the original source-image.

Williams is now moving (no pun intended) into working with dynamic figures: stills from films/videos that feature bodies in motion. The difference in process appears to be the same repetitive and mediative intensity, but the results are quite a bit different. Her analyses of fighting figures creates an emphatic physicality, even a three-demensionality, in her collages. There’s also a sociological analysis happening. “I was going for a breakdown of the physical language,” Williams clarifies, ” just trying to see where the figures fell, stayed, projected, etc. I’m following the vectors of body parts, creating an abstract geometry that looks at the dynamics of motions and the statics of the environment.” Especially with her recent “Untitled” pieces around this one video (which captures a male-female altercation), Williams establishes a constellation of instigators and spectators, ranging from the brawling man and woman, to the children-bystanders, to the police car cruising by in the background.

This is the next step in a methodology that Williams has been working with since she studied fine art at The Cooper Union in New York City. The critical point of “urgency,” which is still a vivid part of her newest pieces, first came up when she described her relationship with the Xerox machine and the freedom of playing with the limits of the medium. Through this tool, all conditions are variable: size, color, scale, saturation are all at the direct, and immediate, discretion of the machine’s user. It’s also a machine that is not accessible or used in quite the same way in Germany as it is in the United States. This represents another important focus for Williams: that of the emigration of practice for our nomadic, creative class. This month Williams will be curating an exhibition on American artists living in Berlin at Altes Finanzamt in Neukölln, which deals directly with this issue of artistic emigration, escapism, and what it can mean to leave everything behind.

Kandis Williams’ practice is rooted in Berlin and the diverse creative community it supports, but her work will be exhibited internationally in the coming months. Besides the show she is curating at Altes Finanzamt (which will also be featured on NPR-Berlin and Reboot FM), she will be in a group exhibition curated by Saskia Neumann on Neue Kanstrasse in early September, and a solo exhibition in November at Otto Zoo gallery in Milan. Her exciting collaborative work, as seen with James Brittingham and Broken Dimanche Press’s John Holten, is extending her process further by starting a choreography company with Jessie Holmes. Whether it’s bodies as textiles, bodies as collage, or bodies in motion, Kandis Williams is pushing how one conceives of and represents the human body in the 21st century.

Artist Info

kandiswilliams.com

newcapitalprojects.com

Writer Info

Elizabeth Feder received her Bachelor of Architecture degree from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City and moved to Berlin in 2010 to further her architectural and urban research with the Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst. She is currently writing for a number of art and architecture platforms and is practicing as part of the [M] AD Design & Architecture team here in Berlin.