by Ester Ippolito, Monica Salazar, studio photos by Adam Tyson // Feb. 28, 2011

Contradictions, humour and questions about knowledge permeate Romeo Alaeff’s work which includes a variety of mediums from drawing to film. An artist based in New York, Romeo has a colorful family history (explicitly explored in his now 16 year documentary series There’s No Place Like You (Previously Still Life With You)) that has no doubt informed his preoccupations with emotion, memory and knowledge. An obsession with Epistemology, the theory of knowledge is pervasive throughout his work. Perhaps more than asking what knowledge is, his work focuses on how we know what we know and the personal or societal consequences of that knowledge.

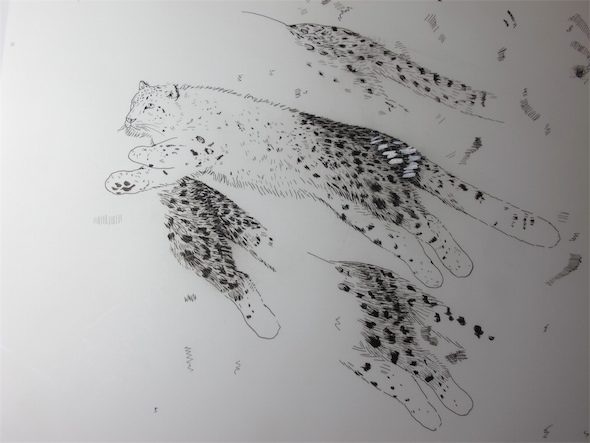

His work frequently includes text, used both to tragi-comically point out the evolution, seriousness and absurdity of being human as in his Evolution of Despair series (2004-2011), and also to create an ironic interplay between text and image as in his sardonic “Life is Not Funny” series (2008-2011). The textual components in these series are integral and seem to open up the works to multiple levels of interpretation. Such interaction with the viewer is a critical aspect of Alaeff’s work. In The Evolution of Despair series, the images juxtapose intricately detailed drawings with darkly humorous text. From the mouths of hand-drawn pen & ink animal characters come all too common sentiments of emotional despair: a turtle says, “I’m damaged goods”, a giraffe; “I must be in denial” and a goldfish; “I feel like I’ve been holding my breath forever.” These images draw upon the grey areas in society, the places where contradictions are rampant; between love and hate and in the strain of human relationships or existential angst.

In the Evolution of Despair series the text and the animals act as mirrors which allow the viewer to project their own narratives on to them. When complex emotions are placed on animals that could not possibly feel them there is a realization of both tragedy and absurdity. The animals are easy to relate to because of the authenticity of the commentary–they are surreal but also deeply familiar. Alaeff drew inspiration from the use of animal characters in children’s books and television (Romeo worked as an animation editor for several years for Nickelodeon, Disney and PBS) which are made to help children deal with their emotional growth. This concept morphed into creations for adult viewers, navigating an environment of social mores, self-doubt and suffering.

Alaeff’s attention to detail and to more anatomical correctness has progressed over the years. While the first animal images were more cartoony in style, later images are highly exact. In fact, Alaeff’s desk is now equipped with the tools a biologist or naturalist might have. This series is will soon be published as a book, I’ll be dead by the time you read this: The Existential Life of Animals (Plume/Penguin, November, 2011). Sticker versions of the animals were tagged around the globe as far as Cairo and Finland and are featured in the recent book that chronicles the history of sticker/street art, Stuck-Up Piece of Crap: Stickers from Punk Rock to Contemporary Art (Rizzoli, 2010) alongside works by Warhol, Damian Hirst, Shepard Fairey and Banksy. The success of this series beyond gallery walls reinforces the idea that the themes in Romeo’s images are relatable precisely because they are quintessentially human.

There’s No Place Like You, a series of semi-autobiographical films dating back over 16 years is all about perspectives and stresses Alaeff’s interest in epistomology. The series follows the relationships within his family and ex-girlfriend, not only in how they live their lives, but how their worldviews affect their relationships to each other. The first video in Romeo Alaeff’s series of “short stories” begins by leading the viewer through Alaeff’s complex family history, describing everything from his father’s shift from diamond cutting in New York City’s Diamond District in the 70’s to cocaine dealing, to his mother’s remarriages and switching of religions from Judaism to Christianity and back again, all in the same matter-of-fact yet darkly humorous way. Perhaps we are not so much learning about these characters’ pasts, as about how their experiences and stories have shaped the artist’s own understanding of knowledge and how it is acquired and manipulated.

Over the course of five years, Alaeff’s work has shifted mainly to prints, drawings and watercolors–he is not medium specific but his ideas are consistent throughout his work. His most recent series, Life is Not Funny, started during a residency in Marfa, Texas, ties into his interest in contradictions and absurdity, especially those dealing with social myths, beliefs and norms. Images like The Creation of Adam quote the traditional (Adam’s hand from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel masterpiece The Creation of Adam (ca. 1511)) alongside the ironic and humorous digital (God’s hand is replaced by the emblem for the original mouse icon, the iconic pixelated finger pointer). Knowledge, once considered received from on high, is, in the age of the Internet, a largely self-directed pursuit, but is it any less mystical? Any less elusive?

His Rorschach series of prints, War on the Brain (2007), were made at the Glenfiddich residency in conjunction with the Dundee Contemporary Art Center in Scotland. The Rorschachs comment on the nature of invisible biases. The 5-6 foot serigraph prints (some made on Andy Warhol’s old press) are saturated with images that have shaped our visual understanding of the world, making bias inescapable. These images are highly skeptical of the Rorschach methodology and its use in Psychology. While the images appear similar to conventional Rorschach patterns they are actually composites of various pictorial elements (iconography, journalistic images, propaganda, and so on) that are related to the subject matter of the print such as Vietnam or the Wars between England and Scotland or rumors surrounding the death of Marie Antoinette or the public image of Muhammad Ali. Some viewers quickly recognizes familiar images in the overall abstraction if they have seen the images before, or they may not or cannot see them at all if not. The images create an intersection of projecting and being projected upon.

Romeo Alaeff’s work suggests that the acquisition of knowledge is no simple process. How we know what we know is as infinitely complex as asking what is knowing? Out of such deeply philosophical questions come images that are both tragic and comic.