Ayse Erkmen – “bangbangbang” (2013), a crane and a buoy; courtesy Galerie Barbara Weiss (Berlin, Germany) and Galeri Manâ (Istanbul, Turkey), photo: Servet Dilber

Ayse Erkmen – “bangbangbang” (2013), a crane and a buoy; courtesy Galerie Barbara Weiss (Berlin, Germany) and Galeri Manâ (Istanbul, Turkey), photo: Servet Dilber

Interview by Marta Jecu in Istanbul; Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2013

This interview focuses on some of the controversial issues surrounding the 13th Istanbul Biennial, titled “Mom, Am I Barbarian”. In a discussion with artist Funda Özgünaydin, we addressed some of the statements made by the Biennial director, Bige Örer and the curator, Fulya Erdemci. Funda is a German Turkish artist and a newly arrived artist-in-residence in Istanbul. Her work refers to the local current political and social issues in Istanbul and projects them into her own situation and it’s controversies. Funda talked with me about her problems regarding her resident’s flat, chosen by Berlin’s Senat new Partner in Istanbul Diyalog. which she says does not fulfill basic living conditions (not fully functioning electricity, an insalubrious environment and located far away from the cultural center). Funda’s work during her residency time in Istanbul is a meditation on this situation. She defines herself as “a cultural observer who takes her own biographical experiences and the immediate social structure as a starting point in creating her translations, concepts and works.”

Halil Altindere – “Wonderland” (2013), video; courtesy the artist and Pilot Gallery (Istanbul, Turkey), photo: Servet Dilber

Halil Altindere – “Wonderland” (2013), video; courtesy the artist and Pilot Gallery (Istanbul, Turkey), photo: Servet Dilber

MARTA JECU: Do you consider that the theme of the biennial – the power of public space in terms of social struggles, arts and politics – has been represented by the curatorial concept of the biennial in relation to the Istanbul context? In the curatorial statement it is claimed that the planned biennial was reoriented after the Gezi movement broke out and the public art program was literally displaced from the public domain. The curator Fulya Erdemci justified the fact that she was renouncing the public art program, by the fact that she would have to receive permission from the same authorities against whom the street protests were directed. How do you appreciate this strategy of non intervention and the claim that withdrawing from public space can mark the presence of participatory demonstration; through absence.

FUNDA ÖZGÜNAYDIN: The first thing I asked myself is: can one bring a resistance into a white cube? And a further questioning: can one actively engage art – art shown in an exhibition or showrooms planned in advance – in an active anti government resistance? I am asking myself a number of other questions: who are we to talk about the Gezi protests and actively engage as such? Are we artists just there to translate our vision and biographical experiences into conceptual works and our knowledge (experiences) into a visual language? Are we there to educate or inform ourselves, rather than to take advantage of the current situation? Are we here to make one aware by questions/questioning?

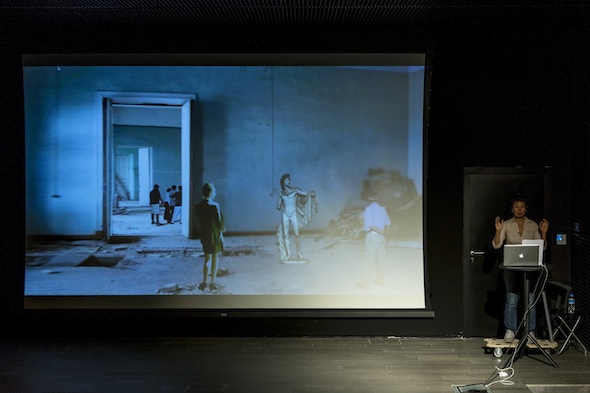

Hito Steyerl “Is the museum a battlefield?” (2013), video documentation of nonacademic lecture; courtesy the Public Program at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (Amsterdam – the Netherlands), photo: Servet Dilber

Hito Steyerl “Is the museum a battlefield?” (2013), video documentation of nonacademic lecture; courtesy the Public Program at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (Amsterdam – the Netherlands), photo: Servet Dilber

I think the curatorial position and the elaboration of the curatorial concept was taking shape before the Gezi protest had fully climaxed. To handle and to re-curate the original concept in a new space, in this particular political environment, was definitely not an easy task. Close to the opening days of the biennial people poured into the streets again to demonstrate against the violence towards a 22 young man that got killed in Hatay during the protests. The exhibition space ‘Salt’ on Istiklal street had cancelled their opening of Gülsün Karamustafa. Several parallel openings were fully functioning during the days of the preview of the biennial and overshadowing the fully equipped police patrols and civil Police on duty. Visitors of the Bienale must have had a strange aftertaste regarding all the happenings in the artworld. Do people and activists deliver their daily responsibility and work? Yes they do!

I was also asking myself if it wouldn’t have been better to postpone the biennial? Or if it would not have been better to place these artworks partially into the public space, for example in functioning shops, or in fruits and vegetable stalls or even integrate them into weekly markets held in every neighborhood? Taking as an example the beginning of the Gezi protest, where the people got collectively and creatively organized, the biennial could have modeled its structure. Do we need permission for doing that – is it too dangerous without it – can you risk it? I guess you can not wait for permission to do all that. There have been many performative acts during the protests: for example the Turkish airlines staff changing the take off security procedures as a collective protest performance on Taksim square. Another example was the piano placed in the square in the middle of the protesters and the endurance performance of the so-called “standing”man, Erdem Gündüz, who spent several hours silently and solitarily standing. Even the daily graffiti all over the City was full of witty, ironic messages addressed to the government.

Funda Özgünaydin – “Euphrates. Insubstantial Utopia”

Funda Özgünaydin – “Euphrates. Insubstantial Utopia”

There have been also a few works on display which address some of these issues directly, for example Hito Steyerl‘s work Is the museum a battlefield? on the controversy of the main investor of the Bienale being Koç Holding, also a supplier of the Turkish army. Ayse Erkmen‘s work bangbangbang, where a huge plastic ball hanging on a crane incessantly hits one of the biennial venues, Antreop 3, alluding to the fact that Antrepo will be rebuilt as a 5-star hotel, possibly by the same Koç holding group. The work is revealing of gentrification issues happening right on site. Halil Altindere‘s video work points to the frustration of Roma youths from Istanbul’s Sulukule, who were forced out of their historic “homeland”, because of the redevelopment of this district. Even the exhibition site, Depo Showroom in Tophane, was not very well accepted by the locals since, with its apparition, house prices went up and they were forced to leave their homes.

Funda Özgünaydin – “Euphrates. Mulberry II”

Funda Özgünaydin – “Euphrates. Mulberry II”

MJ: Even before the Gezi park protests and the ambiguous position expressed by the biennial in this context, some tensions arose regarding the fact that the biennial is sponsored by Koç Holding, one of the biggest holdings of the country. Some artists staged performative protests against this dependence of the biennial on Koç. Disputable, most of all, is the assertive claim of the curator that the biennial intends to “distance itself from the global art market and assessment criteria determined by corporate interest” (from the Biennial Guidebook). How do you view this situation and how was it received by the art scene in Istanbul?

FO: The situation is ambiguous. Salt, another one of the main sites of the biennial, is a place that organizes many talks, that informs, that is ecologically oriented, but Salt is also a traditional showroom. Tanas, the Turkish contemporary showroom in Berlin, is also sponsored by Koç. It is a shame that it will close down, since it gave us German Turkish artists a voice and connected us with our colleagues from Turkey. The weekly held open dialogs on Saturdays I will miss of course…and bumping into Rene Block…

Funda Özgünaydin – “Goats protesting”, c print, photo series in connection with 2 video channel installation

Funda Özgünaydin – “Goats protesting”, c print, photo series in connection with 2 video channel installation

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

13th Istanbul Biennial

Sep. 14 – Oct. 20, 2013

Istanbul, Turkey

See more of Funda Özgünaydin’s work:

www.fundaozgunaydin.com

___________________________________________________________________________________

Marta Jecu is presently a researcher at CICANT Institute in Lisbon, and has contributed to various magazines, including E-Flux, Kaleidoscope, Journal of Curatorial Studies, Idea Arta+ Societate, and various critical books, such as Visual Studies, Ed. Jim Elkins.

www.thinkaboutspace.net