by Graham Haught // June 25, 2014

A few months ago I was tutoring a university student from Freie Universität on writing essays in English. At some point, after the lesson was over, we began talking about Sartre, particularly focusing on his dramatically enigmatic relationship with Simone de Beauvoir: they had separate apartments, saw each other a few times during the week. This type of individualistic partnership netted these two writers closer to each other and to themselves. I told the student I thought that their relationship was intriguing, perhaps even romanticizing it a bit. The student told me the only thing she thought interesting about their relationship was that de Beauvoir was beautiful and Sartre was ugly.

Amalia Ulman: ‘@ The Mayfair Hotel Downtown LA’, 2014 // photograph copyright of Amalia Ulman

The point I am making with this anecdote is that behind every person, object, or statement there exists something much more complex than the simplicity of what its exterior implies. Few have the courage and motivation to explore concepts and objects past the parameters of their own understanding of them. Amalia Ulman does not shy away from those difficult questions. As an artist, a researcher, an experimenter, Ulman develops ideas and works of art that are concerned with individualism, capitalism, feminism, sex work, trends, narratives, and aesthetics. The works are not merely egotistical analyses of Ulman herself, but rather look at universal concepts that can be approached by all. I must note that Ulman is passionate and energetic, it seems as if she doesn’t need to sleep much; perhaps she’s driven by a different wind.

Some weeks ago, Bullet Magazine published an interview with Amalia Ulman where she made a powerful statement about beauty in the art world: “The problem is that in an atmosphere like this, women become some sort of entertainment, and if the female artist happens to be attractive, then the purchases are symbolic, as if someone was buying her arms, or her lips, or one toe.” Talking with Ulman, we discuss topics that cover her current work and her thoughts on embedded narratives in objects.

Graham Haught: What are you currently working on?

Amalia Ulman: I have three solo shows lined up, which will end up functioning as a triptych, in which the artworks (very different bodies of works in very show) will complement each other as a whole. They’re about time and the perishable human body, in different ways. But in general they’ll be getting to that idea by elevating disposable objects (from pocket calendars to flesh) to the status of luxurious fine art objects. This is why I’ve been interested in calendar design for a while, for example, because it is something that has such an expiry date from the very moment it is conceived. There’s a little bit of death in every clock and in every calendar.

I used to collect stamps and go to stamp collector conventions when I was about 8 to 10 years old. In these conventions and markets there were also people who collected coins and people who collected pocket calendars. That, my mother found dreadful, because we used to burn all the calendars we owned every December 31st. I still remember the smell of the paper burning and the feeling of throwing it all out the window. My mother loved new calendars.

The thing is, later in life, I grew very close to someone with Aspergers who had a phobia of linear planning and journals, which made our life together very difficult, because contemporary living is regulated by this time structure. At that point, we were trying to invent a new type of formula, where days would last 2 days (by being awake 24hrs and sleeping other 24). And at that time I also read a very good pdf titled Today Was Once A Holiday Sometime, which is a selection of writings on time compiled by (friend and great artist) David Horvitz.

What I found revealing at that point was how every dictator had tried to change the organization of time and the structure of calendars; the same way a manipulative lover had tried to dominate my sleeping pattern by telling me when to sleep and when to stay awake, going against the rules of social conventions, and my own body clock, making me feel physically sick many times. And I feel that calendars, as we know them, are something so quirky and stupid because they are trying to hide something that in its core is extremely terrifying: death. This, is something that’s related to other things I will be talking about in the other shows, like maternity and childhood: where hospital privacy curtains will be transformed into paintings and where simple handmade wire figures will become giant public sculptures.

GH: One of the aspects of your work that intrigues me is your treatment of individualism within the market, specifically in Buyer, walker, rover (April, 2013). Are you interested in talking about that right now?

AU: Because of how modes of production are changing, I’m now specially attached to this past research because of recent events like the strikes that took place recently in China.

As someone attracted to ruins, failure and sadness, these objects have a whole other meaning when they signify abandonment.

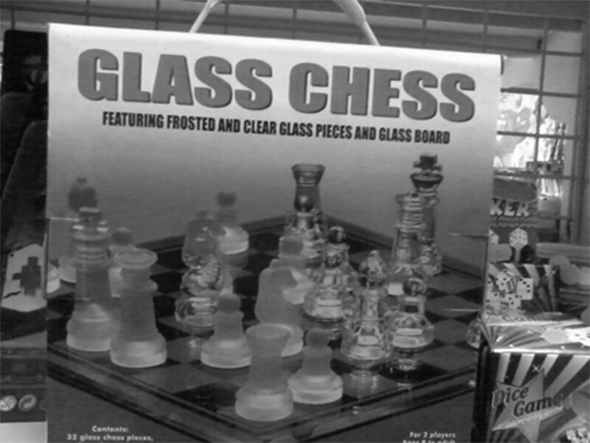

I’m kind of romantic about objects in general because I don’t consume objects. All I have fits in a suitcase. I take pictures of objects and look at them, analyze them and imagine the stories behind them. For example, I wanted to buy a chessboard recently. I wanted a normal one, a wooden one, a nice looking one, and so I first looked on eBay when I was in America. Most of the first search results were glass chessboard sets. There were so many of them and they were the cheapest option. I thought that maybe it could be cool to buy it, but then I thought “oh, never mind, I’ll wait and buy the normal wooden one.” When I was in Spain I went to one of these Chinese stores to look for a chessboard and they only had the glass ones too!

Then I started imagining this situation when someone in the creative department of a company, a few years ago, thought that it’d be the coolest idea to fabricate this chess board, explaining his peers why people would go crazy about them and how it’d be a massive success. And then I see the world overwhelmed by all this glass chess pieces that no one wants, and it makes me want to adopt them and take care of them.

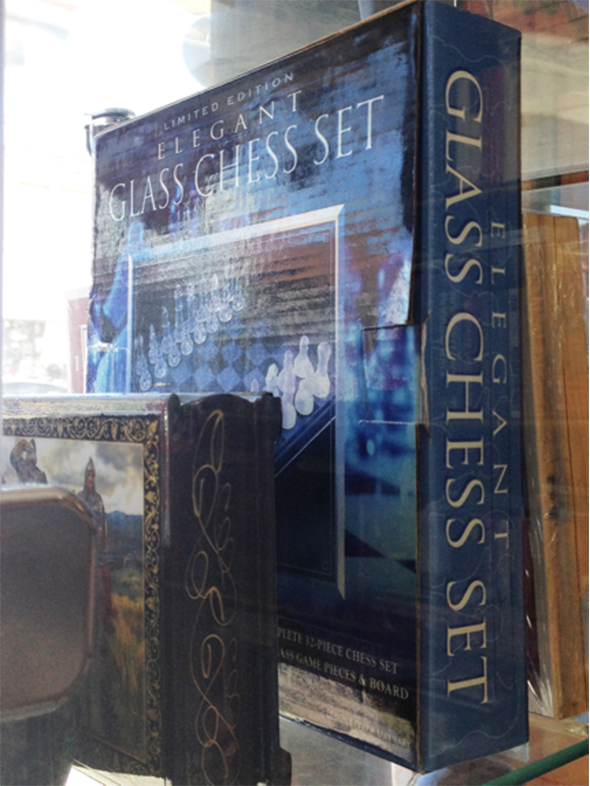

Ebay search for cheapest Chess Board

Glass Chess at Spanish Euro Store, 2014

Elegant Glass Chess at The Russian Bookstore, Los Angeles, 2014

GH: You said that you are interested in objects, but not in purchasing them. Do you feel that in a way you have a more connected relationship to these objects because you have the ability to frame and position them (essentially create the image of the object, and thus the object) rather than simply buy them?

AU: I hate accumulation, that’s the only reason. I hate physical clutter in my life. The only reason I like computers is because of the possibility of digitization and saving space. I thrive for lightness. I don’t like having to take care of things other than my body and a few clothes.

GH: You move around a lot, right?

AU: After leaving London I was living in a different place every month, depending on where I would have a solo show. But then I found Los Angeles and then I lost the ability of running away. I feel the urge of escaping from places, but now because of physical limitations I can’t do that as often, so I turn myself inwards and I write a lot more.

GH: On your website you have a lot of different pieces you’ve written. But at the same time, you tell a narrative through the photos you share. Which medium do you feel is more effective in conveying what you intend?

AU: I like both of them. My work is very influenced by diaries, like having a notebook: that’s my practice. Everything comes back to that. The way I express myself best is through books. Even if I do a video, it still has that structural image form. In my case, text and images compliment each other. I work in a rhizomatic manner and do many things at once as one single piece. Like a puzzle, everything makes sense only when the pieces are put together. I produce many art objects too. A lot of people think that I don’t, but I actually make a lot of works which are my main source of income and which support other aspects of my practice, like writing stupid poems when I feel lonely.

Amalia Ulman: ‘untitled iOS Photo Album’, 2014, photograph // copyright of Amalia Ulman

GH: Do you have one artist or writer that you admire, who is able to converge all their mediums into a form of expression (similar to what you are doing)?

AU: I think that most of my contemporaries work like this because this is how our brains are wired. I think institutions and the art market really need to adapt to this instead of the other way round. I’ve seen the work of my most talented friends gradually becoming more and more flat with the time because of this. It’s just sad and disappointing.

GH: What are you currently reading?

AU: Playing the Whore by Melissa Grant, The Cosmetic Gaze by Bernadette Wegenstein, History of Sexuality by Michel Foucault, Whores and Other Feminists by Jill Nagle, Caliban and the Witch: the Body and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici. Amelie Nothomb’s latest three books. Maggie Gyllenhaal reading Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. I read so fast that books just pass me and I forget everything that I read. Oh wait! The Shaking Woman Or A History of My Nerves by Siri Hustvedt. I didn’t have Wi-Fi in my house for a month, that’s why I read so much. I loved it though, I watched like three films a day and read two or three books a week. [Laughs].

GH: Have you had one specific experience with a work of art that was powerful to you?

AU: Yes, I’ve had moments of feeling like ‘Oh this is beautiful I want to cry’. I will never forget — maybe I was ovulating [laughs] – this piece by Guthrie Lonergan. It’s from 2009 and it’s basically this video of clouds and an a cappella version of an Oasis song, and it’s perfect. When I saw the piece, I cried. Whenever I go back to it I feel very strongly about it.

I recently visited the Made in L.A. show at the Hammer Museum and I cried twice. Firstly, I got over excited with the works by Jennifer Moon and then I wept while watching a video by Judy Fiskin. This happens to me a lot with music. I’m really inspired by music. The latest song I’ve felt strongly about was Swan Song by Luka. And Schubert’s Impromptu Op. 90 No 1 in C minor always makes me shed a tear because I used to use it as a wake up alarm during a very messy period of my life.

Artist Info

amaliaulman.eu

instagram.com/amaliaulman

Writer Info

Graham Haught is an artist and writer originally from California, now based in Berlin.