by Alison Hugill, studio photos by Claudio D’Alò // July 9, 2014

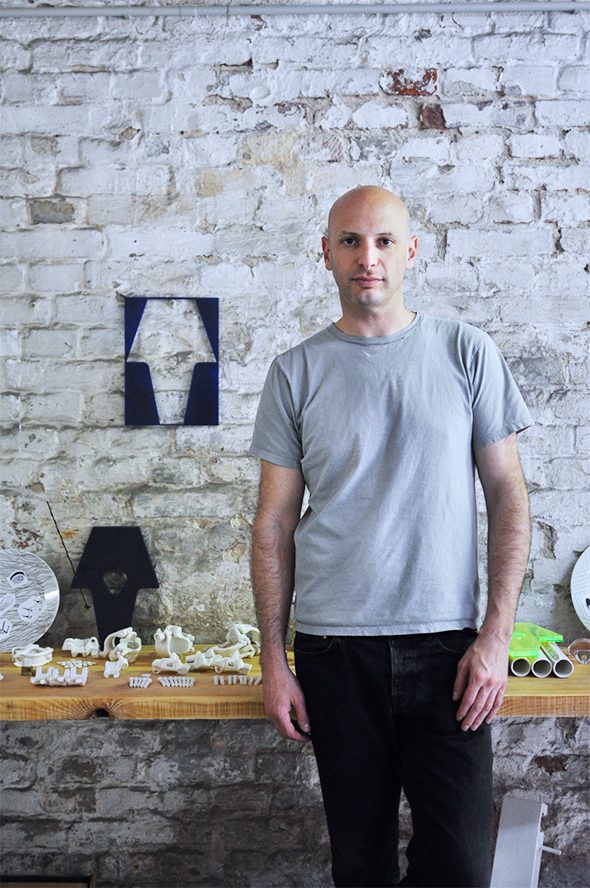

Eyal Burstein points nonchalantly to the four corners of his Kreuzberg hinterhof studio space and labels them for me: “these are my prototypes, this is where I photograph the works, this is the tax section, and this is where I chill out.” When I ask him to see some finished works, he assures me that “nothing’s ever finished.” Prototypes, then, are what we see: launching pads for infinite reconsideration.

The actual construction work happens in the back room, where Burstein has a collection of power tools and highly noxious glues on his work table. It’s also where he’s finalizing a recent piece: a dining table punctured through with porcelain tea cups, saucers, and silverware. The surreal design, dripping with black epoxy underneath, is meant to conjure the complex network of decorum and familiar tension common to the average family dinner.

Burstein studied Interaction Design at the Royal College of Art in London and his oeuvre straddles the borders of functionality and pure aesthetic. Occasionally, it ventures into the realm of philosophy and scientific inquiry. His digital Eye Candy lollipops and his ominous Mind Chair form part of a series dedicated to perception and the plasticity of the brain. The designs operate at a sensorial level, to explore the possibility of new ways of seeing. The series was created in collaboration with cognitive scientists, and tested on late-onset visually-impaired people. The chair – the technological apparatus of which resembles archaic shock-therapy equipment – sends sensations to the sitter, which suggest certain forms, colours, contours, and motion. The works claim to employ “cutting edge Sensory Substitution Technology to transmit vivid emotive images into your mind’s eye.”

Burstein’s studio is located in a recent pop-up creative hub – consisting of the Etsy Berlin headquarters, several design studios, and the restaurant Vabrique – which he seems ambivalent about. His studio is tucked in the back, a kind of shabby relic to the pre-hub days. He has scrawled his name ‘Studio Eyal Burstein’ inward-facing on the door, perhaps to reinforce his non-conformity to the open ideology of the ‘creative class.’

The display table of prototypes in his studio contains some of Burstein’s more well-known design pieces. He has recently launched a re-make of the 1950s Homemaker series, originally created by Enid Seeney and produced by Ridgway Pottery. The china design was mass-produced for sales in Woolworth stores in the UK. Burstein has collaborated with 1882 Ltd. to create an interpretation of the Homemaker series, titled RCA06, after his 2006 graduating class. The six-piece dining set features images of products by Burstein and his RCA contemporaries, Peter Marigold, Max Lamb, Joe Malia, Glithero, Oscar Narud, Raw Edges, and Study O Portable.

Also featured on the prototype table, Burstein’s Scaffolding series finds alternative uses for the construction aid dotting our everyday urban landscape: he turns scaffolding rods into lighting, designed to illuminate dark paths in areas where buildings and sidewalks are shrouded in scaffolding. He has also created a series of porcelain scaffolding joints and rods. The pieces are extremely fragile, confusingly presenting themselves in the guise of a notoriously sturdy material, used to support workers and hoist heavy loads. Even the nuts and bolts of the scaffolding joints are made of carefully riveted procelain. Burstein won’t guarantee the structural integrity of his designs, making them more easily categorized as art pieces. (Though perhaps the distinction is irrelevant in the design world).

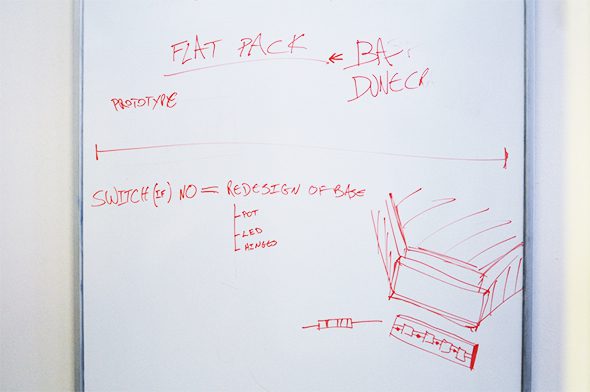

The question of classification has been of great interest to Burstein, especially since he moved to Germany. He tells me about the bizarre and seemingly arbitrary taxation his works have faced when being transported to and from the country. Depending on whether they were being classified as artworks, design products, or curious in-between objects, they were subject to scrutiny and wildly diverse taxation. As a result, Burstein has become somewhat of a tax expert. In 2011, he published a book Taxing Art: When Objects Travel with eminent architecture and design publishers Gestalten.

The “tax section” of his studio starts to make sense, since clearly he has to spend a lot of time and energy navigating the bureaucratic hoops of the trade. This comes from the fact that Burstein’s work is difficult to categorize, which is also what makes it interesting. From scientific exploration to abstract installation pieces, the objects produced by Studio Eyal Burstein present endless possibilities for how design can figure in and contribute to new understandings of the quotidian.

Artist Info

Writer Info:

Alison Hugill has a Master’s in Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on marxist-feminist politics and aesthetic theories of community, communication and communism. Alison is an editor, writer and curator based in Berlin.