Interview by Alena Sokhan in Berlin; Thursday, Dec. 11, 2014

Thomas Struth “Untitled”, photo courtesy of This Place

Thomas Struth “Untitled”, photo courtesy of This Place

Frédéric Brenner spoke to Berlin Art Link about his role as the driving force behind This Place, an artistic project involving 12 world renowned, established photographers and the unstable social and physical landscape of Israel and the West Bank. The project was first proposed as an idea in 2006, and grew into a significant collaboration between Wendy Ewald, Martin Kollar, Josef Koudelka, Jungjin Lee, Gilles Peress, Fazal Sheikh, Stephen Shore, Rosalind Solomon, Thomas Struth, Jeff Wall, Nick Waplington and Frédéric Brenner. The artists participated in an ongoing conversation and 6 month long stays in Israel and the West Bank between 2009-2013, in order to produce individual series of works.

Frederic Brenner “The Weinfeld Family” (2009), photo courtesy of This Place

Frederic Brenner “The Weinfeld Family” (2009), photo courtesy of This Place

Alena Sokhan: This project was a long time in the works. How did you go about setting up an open visual dialogue between established artists and what were some unexpected results?

Frédéric Brenner: While respecting the individual nature of each artist’s work, the project created formal and informal structures for fostering a collaborative spirit among the group. The most important of these were three meetings held during the course of the residencies when the photographers met, shared their work, and offered suggestions for the advancement of the project as a whole. Jeff Rosenheim, photography curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a consulting curator to the project, remarked on how rare it was for artists to gather and share their work – especially work in progress. Although these meetings and other encounters between the artists did not necessarily affect their individual work, they did have a major impact on the project as a whole, as the photographers became active participants in advancing the overall work.

AS: The balance between anticipation and chance has a significant place in the role of photography. When staging an encounter between artists, how much control do you have and how much do you leave to chance?

FB: We were committed to giving the artists all the resources and freedom they needed to make their best work. It was a very open invitation in which we did not seek to predetermine the content of their work or to control it in any way. Paradoxically, this freedom and openness to chance required that we invest a great deal of time in the selection of the photographers. We wanted to have a very diverse group, with different backgrounds, perspectives, practices, and visual grammars; we also wanted artists who used their cameras to ask essential questions about culture, society and the lives of individuals.

We also introduced the artists to thinkers and activists who we felt could enrich their experience of the land and its inhabitants, and we paired them with local young photographers who not only served as technical assistants, but also served as guides, translators, and daily collaborators. Perhaps most importantly, we gave them the time to immerse themselves in their work. Most photographers spent about six months in the region over a period of three or four years.

Wendy Ewald, “Bedouins, Amal”, photo courtesy of This Place

Wendy Ewald, “Bedouins, Amal”, photo courtesy of This Place

AS: What effects (if any) does the digital age have on artistic collaboration, particularly in overcoming spatial or temporal limitations to communication?

FB: The web, email, Skype, file-sharing, etc. of course made it easier to run such an international project, but what was more interesting for me was the subtle ways the development of digital photography affected the work of some photographers. Most of the photographers were – and are- deeply attached to film, but during the course of the project, several photographers began to experiment with digital techniques.

The most dramatic case was Wendy Ewald. Wendy has spent the past thirty years collaborating with communities to make pictures, but here for the first time she decided to work with digital cameras. She immediately discovered that with these cameras she would work with more communities simultaneously than with her previous projects. As a result, she expanded her initial idea of working with five schools to a plan to work with 14 communities. The scope of her project would not have been possible without digital technologies.

The digital is also an important part of our dissemination plans, as we are using the web and various social media platforms to inspire and sustain a global conversation about the artwork. The digital initiative will include images, essays, interviews, process photographs, and a variety of video and audio, including short films on each artists.

Stephen Shore “Bir El Maksur” (2009), photo courtesy of This Place

Stephen Shore “Bir El Maksur” (2009), photo courtesy of This Place

AS: Twelve artists in Israel recalls the symbolic trope of the twelve apostles. Is that relevant and how do you maneuver such a politically and religiously-charged space where everything carries so much significance?

FB: Twelve is a highly symbolic number – the twelve apostles, as you mention, as well as the twelve tribes of ancient Israel, the twelve Greek gods, the twelve months of the year, and so on — but none of these associations had anything to do with the number of photographers selected for the project. We knew that we wanted a significant number of artists in order to create a true diversity of perspectives and grammars, but we did not decide in advance whether this would be 10 or 12 or 15. The process was more organic and was determined by more practical concerns.

We weighed two competing interests: 1) the more artists we included the more diverse the project would be and 2) the more artists we included the less work from each we would be able to feature in the exhibition. In the end, the project felt full and complete with the 12 artists we had selected by the end of 2010.

AS: Your project looks at Israel and the West Bank as a “place and metaphor” – using a space as a metaphor has implications of neocolonialist appropriation or, alternatively, an empathetic association. How has the show attempted to address the problems of cultural sensitivity in distinguishing between metaphor and representation?

FB: One aspect of this particular piece of earth is that for several millennia it has lived a rich and complex life beyond its own territorial borders. This is in large part because of its significant place in three great monotheisms and three great global narratives: Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. But it also becomes the peculiar metaphor of “the promised land” – the idea that a land (this land or any other land) can have a promise attached to it. This metaphor has been a powerful force in world history, inspiring colonial fantasies as well as acts of liberation.

Consider just two examples from the history of the United States: the early settlers dream of America as a “New Jerusalem” and African Americans’ invocation of the promised land in their struggle against slavery and discrimination. But I am also interested in the psychological and emotional effects of this “promise” and the way in which Israel and Palestine act as a kind of Teatro Mundi, in which our deepest fears and desires are brought to the surface. It is this metaphor that has made this “place” so resonant for people around the world throughout history and today, and that is why I wanted to bring artists from around the world. This project is as much about the world outside of Israel and Palestine as the world inside.

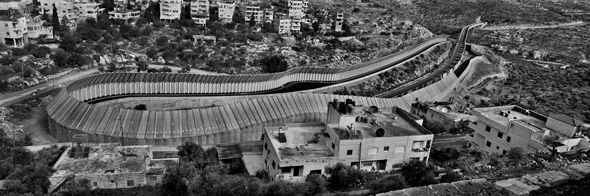

Joseph Koudelka, “Route 60, Beit Jala, Bethlehem area”, photo courtesy of This Place

Joseph Koudelka, “Route 60, Beit Jala, Bethlehem area”, photo courtesy of This Place

AS: The title of the exhibition, This Place, cleverly uses an indexical referent rather than a sign or a symbol, a specific indication towards something. What is the “place” that the photographs are referring to in this exhibition?

FB: As you can imagine, it was a great challenge to come up with a title that could on the one hand capture the vast array of work produced by the twelve artists and on the other hand have real meaning for the viewers of the exhibition. This was made more complicated by the fact that each photographer had ideas about the relationship between the particular and the universal in their own work, and the way this new work related to their past work. This is reflected in the titles to their own monographs: Them, Field Trip, Wall, Daybreak, An Archeology of Fear and Desire, etc.

We needed a title that made some reference to the place because this was the one commonality between the 12 photographers: they all made images in the same geographic space. At the same time, we wanted to make clear that their individual work and the project as a whole was not solely about Israel and the West Bank; it had a more general, even universal, significance. Ultimately, the title This Place was proposed by another curatorial consultant, Urs Stahel, founder and former director of the Fotomuseum Winterthur. On a two-week trip to Israel and the West Bank, he was struck by how many people said “what you need to understand about this place is…” He felt the title This Place elegantly conveyed a dual meaning: “this place” as in Israel and the West Bank, but also “this place” in the sense of this place where I am right now, wherever in the world, with its own complex network of relationships and meanings. I think each photographer refers to multiple places in their work: physical, emotional, and artistic.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

DOX Center for Contemporary Art

“This Place” – GROUP SHOW

Exhibition: Oct. 24 – Mar. 2, 2015

Poupětova 1, (click here for map)

For future locations of this travelling exhibition, check the exhibition website.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Alena Sokhan is working on her Masters in Media and Communications at the European Graduate School. Her research interests lie in the topics of Queer Theory, Critical Theory, Film and New Media Art, and Economics.