With its second exhibition, NOME Gallery is already building up an impressive reputation for bringing bold, politically engaged new media art to Friedrichshain. The first show featured Paolo Cirio’s legally subversive prints of government officials who were exposed for their abuses of power. The current show is titled The Glomar Response and features three works by artist, writer, and technologist James Bridle, which explore the implication of power with visibility, and materiality with information. Bridle’s works are simple in presentation but are grounded in a sharp understanding of jurisdiction throughout history, locating deep trends of power imbalances that have not been resolved in the contemporary age, but rather have taken a new form in a new medium. Like many new media artists, Bridle recognizes the democratizing potential of digital technologies, using his works to help reveal who has the authority to write and apply the law.

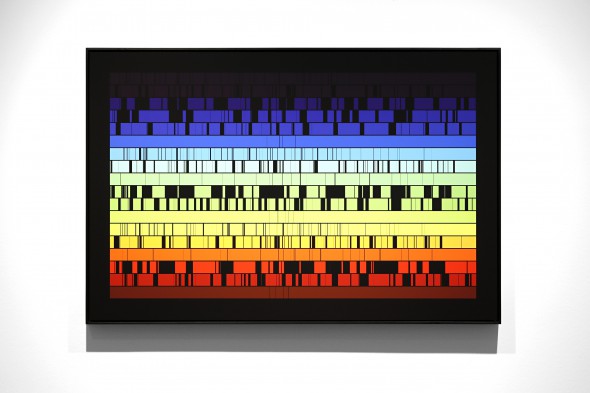

‘Seamless Transitions’ reconstructs three spaces of immigration in the U.K – spaces accessible only to immigrants and government officials involved in immigrant judgement, detention, and deportation – with a computer simulation. The simulation reconstructs the rooms and the interior of the buildings, which we are otherwise not allowed to see or photograph. The viewer can watch these spaces revealed in a short film, brightly lit and ghostly vacant rooms, untrue to their real life state, in which they are filled with people, dirt and noise. The work ‘Fraunhofer Lines’ takes its name from the gaps in the sun’s spectra discovered by Joseph von Fraunhofer in the early 19th century. Fraunhofer discovered that certain frequencies are absent from the sunlight that reaches the earth. Bridle uses the aesthetic of these patterns to visualize the redaction of official documents obtained through ‘Freedom of Information’ requests.

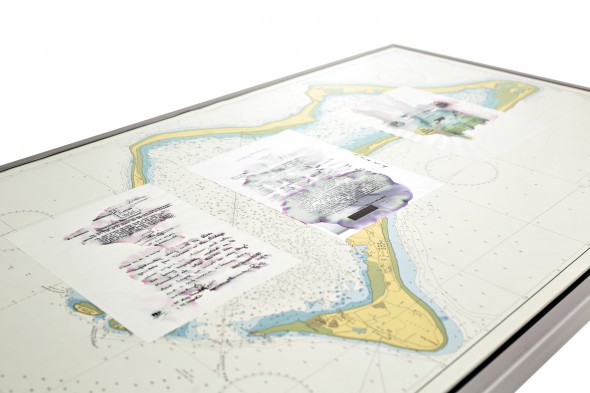

The last work, ‘Waterboarded Documents,’ is similarly well researched, again showing how obscured information reveals the way power and forms of control operate. In 2014, the British government claimed it could not produce any information about its role in the CIA’s global abduction operation program because the relevant files were accidentally soaked with water. With a dry humor, in ‘Waterboarded Documents’ Bridle has inflicted the same water damage to his research into the websites and domains in the British Indian Ocean Territory. The three works are very specific and complex. Without knowing all the underlying information they can be difficult to understand. So last week we had a chance to ask Bridle some questions about this specific show to help clarify what we are looking at.

James Bridle: ‘Fraunhofer Lines (Information Commissioners Reports, 2008 – 2012)’, 2015, 121.5 x 80 cm // Courtesy of NOME gallery

Alena Sokhan: Why did you put together these three particular works in this exhibition: ‘Seamless Transitions’, ‘Fraunhofer Lines’, and ‘Waterboarded Documents’?

James Bridle: All of these works deal with a common subject matter: the role of technology, and particularly communication technologies, in constructing the world around us, the use of those same technologies to visualise, explore and critique the world around us, and – ultimately – the limitations of this approach.

AS: In ‘Fraunhofer Lines’, what is the relation between diagrams of the sun’s spectral lines from 1814 and the redaction of official documents?

JB: Each of these is a study of light itself: how much reaches us, and what it permits us to see. In the case of both Joseph von Fraunhofer’s original spectra, and the documents I use in the exhibition, what is revealed is an absence, a darkness. But this darkness is itself revealing. By looking at the spectral lines, Fraunhofer was able to reconstitute certain elements and reactions taking place in the Sun and the Earth’s atmosphere. By looking at the patterns and forms of redactions in official documents, we can discern the patterns and forms of the politics which produce them.

AS: In ‘Waterboarded Documents’ you demonstrate the materiality and physicality of information, power structures and methods of control. Why is it important for us to remember that communications technologies and information are tangible, physical objects?

JB: Our brains, wonderful as they are, struggle to deal with intangibles. By visualising and concretising them, we make them easier to understand and critique – to hold them in one’s hands, and turn them over, so to speak. By proposing correspondences between network technologies and systems of law and governance I am suggesting both that these are powerful and opaque infrastructures, and that they are deliberate and amenable to investigation.

James Bridle / Diego Garcia: ‘Waterboarded Documents’, 2015, mixed media, 119 x 72 x 110 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/dramaberlin.de, Courtesy of NOME gallery

AS: Your works are often about making the “invisible visible” – as the exhibition publication explains – abuses of power, information, or redaction, for instance. Can you talk about the insufficiency of sight: particularly in the case of ‘Seamless Transitions’, where unlike the other two works in the show, you make visible the object that is obscured, but this simulation is insufficient to express the experience of being in these sites?

JB: The simulation is never enough, but in the case of ‘Seamless Transitions’ what is depicted is precisely not the human experience of being inside these real spaces, but the inhuman architecture of the spaces themselves. How do you draw a picture of the internet? How do you paint a portrait of a criminal justice program? The subject focus of most twentieth-century (and particularly human-rights) documentation points to the experience of the individual within these systems, but for me the interesting challenge in the twenty-first is to depict the system itself, which is, perhaps, what we have been developing the tools to do.

James Bridle: ‘Seamless Transitions’, 2015, animation by Picture Plane, digital video, 5:28 min, commissioned by The Photographers’ Gallery, London, supported by NOME, Berlin, and public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England // Courtesy of NOME gallery

AS: Can you talk about the problematic difference between awareness and concern in contemporary culture, where somehow in an economy of attention, making something visible still does not mean that it will be seen in a meaningful way?

JB: Making visible is not enough, and indeed in certain cases may make the situation worse. But it remains one of the best tools that we have, and it’s the necessary starting point for change, because without it there can be no critique at all. I think your question reflects an even larger one, which concerns me a lot: there’s a common and natural liberal – even Enlightenment – belief that more information, more awareness, leads to more understanding, better actions, better decisions. But what if this isn’t really true at all? Exposure to almost limitless quantities of information, as on the internet, does not seem to lead us to greater agreement, rather, conspiracy and conflict flourish. People cling to fundamentalisms of all kinds. We should perhaps instead be wary of data-driven ontologies, and seek other kinds of understanding, ones which are more comfortable with doubt and contradiction, ones which better reflect the complex world that our senses and our technologies reveal to us.

Exhibition Info

NOME

James Bridle: ‘The Glomar Response’

Exhibition: Jul. 25 – Sep. 05, 2015

Dolziger Straße 31, click here for map