by Alison Hugill, studio photos by Alexander Coggin // Sept. 7, 2015

You’ve likely passed the unusual building on Brunnenstraße, clad with multi-coloured polycarbonate and emitting an opaque lantern glow at night. Perhaps you’ve visited KOW gallery on the ground floor. Architect Arno Brandlhuber and his team at Brandlhuber+ envisioned this design from an abandoned lot, holding the ruins of a 90s, post-GDR investment gone awry. As with many of his other projects, Brandlhuber made use of the existing structure to invent a hybrid of the original context and its contemporary instantiation, explaining that the energy and labour of the previous building should always be taken into account in the new product. The result is a striking bare-bones complex, the top floors of which house the architect’s studio, office and penthouse apartment.

Entering through a covered driveway into the courtyard, a series of concrete staircases come into view, accentuated at intervals with empty terraces. The staircase and terraces are reinforced with a subtle railing, made from a striated pattern of tensioned cable. The interior of the building is stark, emulating the shell-form of a bunker or brutalist construction, but with the polished character of a clearly designed space, perfectly stylized for creative offices and galleries. The architects took into consideration a number of factors in the design, angling the roof at just the right degree to ensure sun in the courtyard, and playing with the regulations just enough to avoid architectural tedium: the rooftop even has its own landscaped tree, seemingly emerging from the building itself, and a homemade plexiglass sauna.

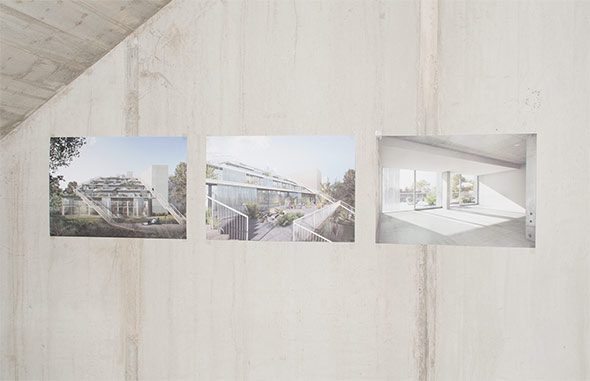

Brandlhuber is the kind of architect who, after many years in the field, appears to have reached a point of notoriety which affords him the time to focus on the more conceptual aspects of his projects. He spoke to us about the theory behind his upcoming collaboration with the Berlinische Galerie, in the context of the 4-museum exhibition ‘Stadt/Bild (Image of a City)’. Brandlhuber+ has teamed up with designer Thomas Mayfried and architect Florian Hertweck to create ‘The Dialogic City: Berlin wird Berlin’ in the main exhibition hall of the gallery. The outcome will reflect the group’s political take on the city, and the narrative of Berlin’s legislation of architecture. Using the recent Tempelhof referendum as a metaphor, Brandlhuber speaks of the way that the referendum’s question was posed, as an either/or problem: to either build on Tempelhof, or not to build on Tempelhof. This dilemma left no room for debate over what kind of projects would be beneficial, or how existing buildings might be repurposed and reinvented. Instead, Brandlhuber suggests an and/and approach, which he regards as specific to the ‘dialogic’ nature of Berlin. He shows us a render of the main airport building on Tempelhofer feld, with the Bikini Haus building from the Kurfürstendamm area integrated on top of the existing structure. The montage suggests possibilities for and/and, without disturbing the open leisure space of the field.

When we met Brandlhuber, he wasted no time to mention that his architectural projects are always a team effort, and we were also hosted by a senior architect in his office, Thomas Burlon. Burlon is the self-professed brawn of the Brandlhuber+ project team, often overseeing the construction as well as the design. He spoke to us about a recent (and ongoing) renovation project: St. Agnes church. Brandlhuber+ was at the forefront of the new design for the Johann König Galerie and the surrounding complex on the site of the former St. Agnes church, an iconic brutalist building, designed in the late 1960s by architect Werner Düttmann. In order to maintain the circulation of the original church complex – built on the principles of the Second Council of the Vatican, wherein the church should be only one part of a larger social network and community, including housing for the church employees – Brandlhuber+ convinced Johann König to include a café, and space for other creative offices, including project space Praxes and fashion and art magazine 032C. The recent renovation of the main church building transformed the gallery into a two-tiered space, with a suspended concrete table dividing the high-ceilinged cathedral in half. The upper section will present shows by König’s artists, while the lower section will serve as storage and office space for the gallery.

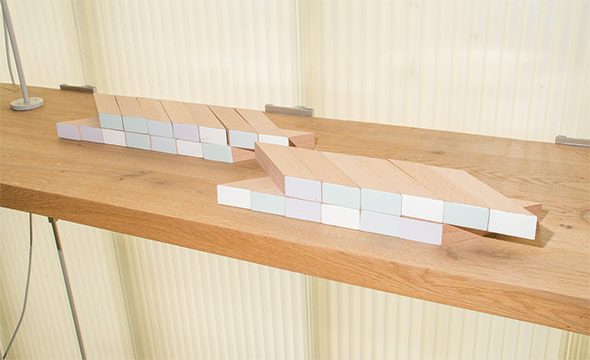

Many of the projects realized by Brandlhuber+ revolve around the principles of enhancing existing built structures through clever design hacks, which allow the architects to playfully push standardized regulations and create more interesting projects that account for the life cycle of the building itself. Beyond these material boundaries, the office is interested in critiquing the political status quo, with projects like ‘RGB (rot gelb blau)’ (2011), a poster campaign pointing out the limits of the spectrum of German party politics, and ‘How Soon is Now’ (2014), a tool to challenge rent prices by creating efficient designs for small housing and workspace units.

While the working area of Brandlhuber+ resembles a regular architecture office environment, the massive floor-to-ceiling windows and polished concrete give the whole scene a distinctly Berlin, industrial vibe. It’s clear that Brandlhuber himself, much like the foundation his office is built on, is still attached to the dream of Berlin, forged in the early 90s, as a place for meaningful critique and endless experimentation.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Berlinische Galerie

Brandlhuber+, Hertweck, Mayfriend: ‘The Dialogic City: Berlin wird Berlin’

Exhibition: Sept. 16, 2015–Feb. 21, 2016

berlinischegalerie.de

Alte Jakobstraße 124–128, 10969 Berlin, click here for map

Writer Info

Alison Hugill has a Master’s in Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on marxist-feminist politics and aesthetic theories of community, communication and communism. Alison is an editor, writer and curator based in Berlin.