Interview by Marta Jecu; Saturday, Sep. 12, 2015

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

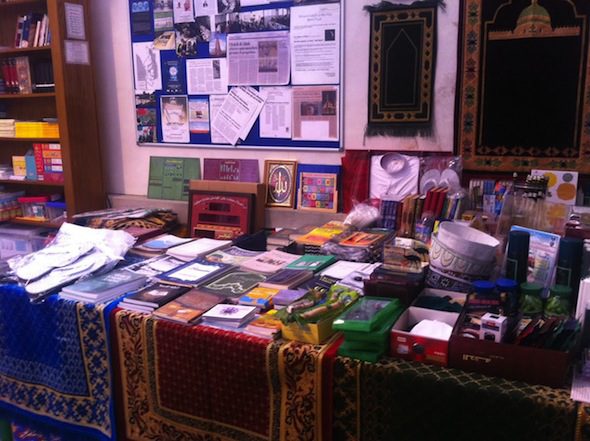

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

The Icelandic Pavilion, transformed into a functioning mosque by Christoph Büchel, was closed down on the 22nd of May, only 2 weeks after the preview opening, causing an immense controversy. The Mosque is situated in the Santa Maria della Misericordia church in Cannaregio, a building which has been dysfunctional for half a century. The Mosque was installed with the help of the Icelandic and Venetian Muslim communities and has been regularly used for the usual religious activities (lead by the local imam Hamad Mahamed), in the days leading up to its closing. The Mosque project represent a no less audacious adventure than any of Christoph Büchel’s previous projects: ‘Piccadilly Community Centre’ from 2011 (that established a functioning community center during the exhibition time at Hauser & Wirth Piccadilly, London); his ‘Der Kunst Ihre Kunst – Der Freiheit Ihre Zeit’, in 2010, in which he placed a sex club inside the Secession in Vienna; or the 2008 ‘Deutsche Grammatik’, which staged the Fridericianum in Kassel as a setting for episodes of German history (with Kassel’s social security offices, commercial areas, Stasi local administration offices and an abandoned museum situation).

Venice’s administration were concerned as a result of the ambiguous situation of the mosque – is it a mosque or is it not? – which could instigate either anti-Islamic or Islamic extremism. They ultimately determined its forced closure. The question of the legitimacy and nature of Büchel’s installation goes down to fundamental questions regarding art’s capacity and most of all authority to establish reality, questions which the officials and the pavilion’s representatives are since debating: if the mosque is a work of art and not a mosque (in the institutional sense), as the artist and curator claim, than legally there shouldn’t be any reason for its closing. On the other hand, if this is meant to be a real mosque, it functions without a permit.

The gesture of converting a former church into a mosque carries with it heavy connotations, bringing a historic row of clashes between ardent and opposing iconodulia and iconoclastia: the prominent conversion of churches into mosques after the conquest of Constantinopole by the Ottoman Turks and the no less coercive 19th century conversion of mosques into churches on the territory of the former Ottoman empire.

Is ‘the Mosque’ a social project? It is not ultimately offering a site for the religious practice of an unfavored community in Venice. It is rather enacting a prototype of a mosque (it does not have characteristics of Sunni nor Shia, but is the assimilation of a historic layering of cultural information, that architecture in Venice represents). It can also be seen as paving the way for the existence of a mosque in Venice, considering that Venice has never had a mosque, despite the historically intensive cultural and economic exchanges with the Islamic world. Nina Magnúsdóttir, the curator of the pavilion, delves into this essential dual and ambiguous nature of any work of art, which reflects back into the debates surrounding the pavilion.

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

Marta Jecu: I wanted to get into some details about the current polemic around the Icelandic pavilion, from a curatorial point of view. I read in the corrections statements corrections statements: “The Mosque is an art project. The installation is a work of art and claims to the contrary are misleading”. Does the fact that it is used as such, however, not establish it as a temporary mosque? And what reason did the authorities give to disapprove of the functions of such an initiative in the context of the biennial and the city of Venice?

Nina Magnúsdóttir: In my opinion there are actually no valid reasons for the authorities closing the pavilion down, and what they do now is look for reasons. It is a strange situation, a bit like in a Kafka novel. Their reasons are technical details that in our opinion to do not have any ground in reality, for example that there should not be allowed more than 100 people people inside the mosque (except for the opening) or that selling things was not permitted in the pavilion. We are in the middle of this process of negotiation with them, in order to be able to open the pavilion again.

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

MJ: The main question, which is actually fundamental in determining the nature of a work of art in general is perhaps: should the mosque be considered both a work of art and a real mosque or only a work of art? It engaged the Muslim communities (in Venice and Iceland) to use it as a place of worship, while speakers from Muslim communities in Venice and Iceland were talking at the opening about how important the work was (since the city’s historical center has never had a mosque). In this sense it corresponds to the paradigmatic definition of performative art: art is not only ‘staged’ (a simulacrum), it is doing what it is saying, it creates a certain reality. And in this case, legal matters interfere.

NM: Bringing the national pavilion to Venice is obviously a work of art, it is a work of art which (in a conceptual tradition) is close to reality. And this is how art generally works. It is hard to consider something in general only as being that which it appears to be. In art, everything is open to interpretation. A work talks on many different levels.

MJ: Reading the debates in the press, as well as the corrections that you have released, I understood that the problem for the officials is that as a mosque it cannot run. It can run only as a work of art and all its manifestations as a ‘real’ mosque have to be averted.

NM: In making this distinction, the authorities are actually interfering with the work itself, saying that if the people have to take off their shoes, than it is not a work of art. If people wash their feet, than its not a work of art. If people pray in the installation, than its not a work of art. The argument of the officials has shifted from invoking the praying and feet washing practices to selling things and the number of visitors. But we of course do not agree with this: because we do not demand of people to take off their shoes or pray, they can do it if they want to. In any case it can be a work of art, even if people take off their shoes or pray. This is all part of the work. Nobody is telling people what to do but they also cannot claim that if these practices are included in the work, than this is not a work of art.

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

Christoph Büchel – Icelandic Pavilion, Venice Biennale 2015; Photo courtesy of Smaranda Olcèse-Trifan

MJ: This reflects back on the question of the agency of the work of art, so objectively speaking we need criteria to delimit the nature of a work. Did you have a permit for installing a mosque or only for making a work?

NM: This is a work of art, this is what we are doing. It is very strange that this discussions goes like this, because for more than 100 years people have been doing works that imply participation. We could not ask for the permit of opening a mosque, since this is not what we are doing. We are doing a work of art. That is also why we consider that there is something wrong in their argumentation and not in ours.

MJ: Maybe your argument regards the work of art and their arguments regards the/a mosque. But as you have invited also the Icelandic and Venetian Islamic communities to use the space, the space is used as a mosque ingeniously.

NM:The Muslim community has collaborated in this project from the beginning. They were well aware of what it is. It would be better to ask them directly about the way they interpreted that, since I cannot answer for the whole Muslim community. People have different opinions, it is for each of them to answer. Works of art cannot be easily defined and it is the nature of art to provoke these questions.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

“All the World’s Futures” – GROUP SHOW

Exhibition: May 9 – Nov. 22, 2015

___________________________________________________________________________________

Marta Jecu is currently researcher at CICANT Institute, Universidade Lusofona, Lisbon and independent curator.