Interview by Alena Sokhan in Berlin; Tuesday, Nov. 17, 2015

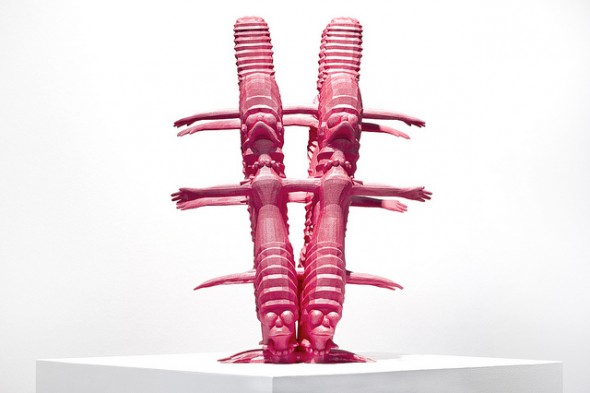

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Gogogogogoku, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 47 x 48 x 33 cm // photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Gogogogogoku, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 47 x 48 x 33 cm // photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez is a British-Colombian artist who has been known for his work with 3D printing, his creative methods for circumventing copyright, and in depth explorations of the uses and misuses of technologies.

His projects are many and varied: most are infused with a great sense of humor – he made 3D scans of artifacts from the Metropolitan Museum of art dance in the short film ‘We Met Heads On’ (2012) – or social value – his work ‘Decoy Browsing Triptych’ (2015) is a free software that will randomly browse Google, Amazon, or Facebook from your account in order to ‘pollute’ the websites’ data collection process with meaningless content. His aesthetics, process, and concept are tightly interlocked in his works, which both represent the current state of digital and communications technologies and introduce new ways of using them.

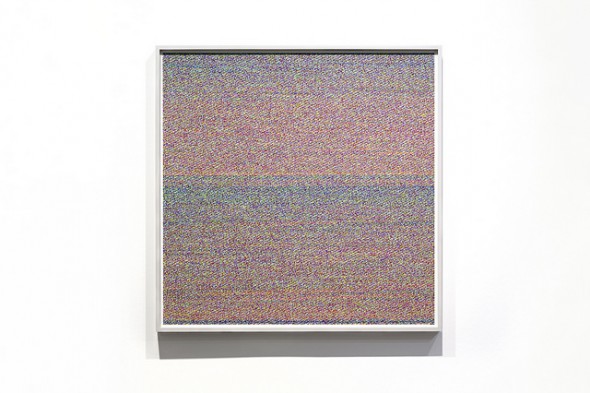

With the current exhibition at NOME, titled Hard Copy, Plummer-Fernandez has produced four 3D prints, made from distortions and glitchy combinations of popular cartoon characters: Marge Simpson, Goku, Spongebob Squarepants, and Mickey Mouse. The distortion is significant enough that Plummer-Fernandez does not infringe copyright, though the characters are easily recognizable. Each print is then translated into a image, not just a simple representation but an image file that contains all the data of the 3D file.

We had a chance to meet with Plummer-Fernandez and chat with him about copyright laws, kitsch culture, and how digital technologies have changed our notions of representation.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Hard Copy, 2015, installation view // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Hard Copy, 2015, installation view // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Alena Sokhan: You have worked with 3D printing and design for some time now. Are these works ones that you developed specifically for this exhibition?

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: It’s been on my mind for a while to have an exhibition that correlates images and 3D prints. With most of my work I can simply display it online, so now I was focusing on what would work particularly well in the gallery space.

I have participated in several group shows already, though doing a solo show is a completely different experience – it’s like living in a shared flat and then getting your own place. I could make all the decisions myself. In this case it was quite important for me that the exhibition actually had a unified concept rather than just being a collection of stuff.

I have also been involved in the process of translating objects to images and back. The question of what the objects should be came much later. I wanted to use popular cultural icons that would be already file-shared and that I could appropriate. I have been working with Mickey [Mouse] a lot, and he appears again in this show. I think now might be the final time I use him.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Every Mickey, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 50 x 24 x 50 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Every Mickey, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 50 x 24 x 50 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

AS: Why are you drawn to Mickey Mouse in particular? He shows up in your works quite often.

MPF: I find it strange that some icons have more copyright issues than others. Mickey is a paradigm of certain privileged parts of culture being untouchable and protected for the sake of profit.

AS: Yes, I remember something about Mickey reaching the end of his copyright?

MPF: Exactly, the Copyright Term Extension Act allowed for certain intellectual property, that is corporate owned works, to extend its copyright beyond the normal allowance. The Walt Disney Corporation was really concerned about Mickey becoming free of copyright. They heavily lobbied for the Copyright Extension Act so that Mickey could prolong his life as a protected asset they could profit on, which is funny because he seems kind of ancient and ubiquitous. More than just the cartoon, he is a marketing graphic that you see everywhere. It shows how copyright laws are clearly not about intellectual property, they are about profit.

The sculpture of Mickey is a little different from the others. The distortion comes from an amalgamation of every 3D file of Mickey that has been shared online, after searching intensively I found about fifteen of them. So here you have a bunch of individual interpretations of Mickey formed into one, superimposed onto each other.

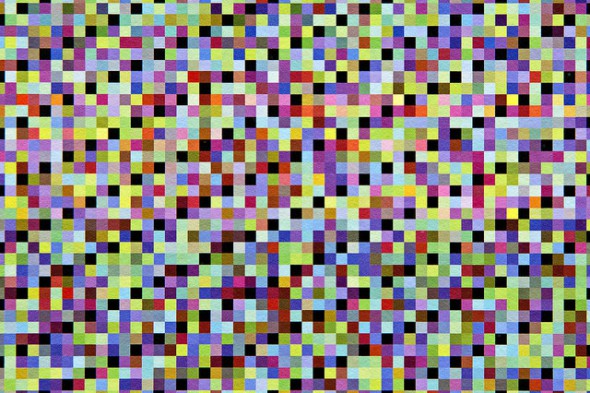

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Every_Mickey.png, 2015, ditone archival pigment print, 100 x 100cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Every_Mickey.png, 2015, ditone archival pigment print, 100 x 100cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

AS: Why is there so much creative energy on the internet? Why are so many people interested in making and printing 3D objects they could easily buy and why do so many people put their time and effort into it for no financial gain?

MPF: I find it really fascinating. I can only speculate, but I think it’s driven by a cultish following. People really obsess over these things. I find the whole world of fan art really interesting because it is seen as kitsch and low brow, but at the same time it’s huge. It’s like the dark matter of culture.

I am interested in file sharing culture because it reveals culture being democratized, culture becoming participatory, and it represents the freedom of the internet, where people just do as they please and not worry about it.

AS: What attracts you about introducing glitches and distortions into popular cultural images?

MPF: Well, I have a natural inclination towards breaking things rather than making them work. I did not actually want to become an engineer or work as a programmer because I could never make anything function or have any utilitarian purpose, so I embraced the opposite, I started to destroy things.

I want to explore the state of things not being perfect in my aesthetics. Computer systems are always designed to appear seamless and perfect, but they are not. Glitches and dysfunctionality seem right for the time that we live in. It makes sense to me that the world that we live in should not be represented by such clean art.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Merge Simpson, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 41 x 22 x 55 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Merge Simpson, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 41 x 22 x 55 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

AS: So how did you decide on the distortions for the other works?

MPF: I started to think about the semantics of different objects. I found it important to push them away from appearing as characters or toys. I did not want these objects to simply become other types of characters. I started to think of them as more symbolic, totemic objects. As if in some strange future this file sharing culture produces these strange objects and rituals.

It’s interesting that in the first place most of these images are flat – they were never meant to become 3 dimensional. For instance, in the cartoons, Mickey’s ears are always face the camera directly so you always see two ears, even when he is in profile. The Simpsons also look very strange in 3D: they have these giant round eyeballs. So when I start distorting the 3D models of flat characters, I quickly developed a sense for the distortions which are possible in the 3D figures of flat images. In ‘Merge Simpson’ the distortions change the facial expressions of the model. It’s the same model stacked several times, though when she is stretched in different ways it changes her facial expression dramatically. In one she kind of looks like she is screaming. The headpieces change as well, so now she kind of looks like a high priestess.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Merge Simpson, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 41 x 22 x 55 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Merge Simpson, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 41 x 22 x 55 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

AS: In what ways is computer modelling different than making a sculpture the traditional way?

MPF: Firstly it involves an act of appropriation, of collage. And secondly, with a digital model you don’t have physical constraints: digital forms can be reshaped, twisted, and moved in ways physical materials cannot. So the forms I create emerge from both of those aspects.

I have a computer modelling program and it’s easy to see the model in virtual space. The program is very responsive, you can easily turn the model around, look at it from different angles. The good thing about modelling like this is that you can just press control-Z and undo what you have done, or you can make many variations of the same thing. And then when you print it you kind of commit to it, and that’s the exciting part, that’s when it becomes real. You can make a hundred digital iterations but when you print you commit to the piece.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Every_Mickey.png, 2015, ditone archival pigment print, 100 x 100cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: Every_Mickey.png, 2015, ditone archival pigment print, 100 x 100cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

AS: The translation of the 3D file to an image is not what I expected – it’s completely non-representative. How did you produce these images?

MPF: The images contain all the information from the 3D file in a PNG file. The program I developed works by translating every point on the geometry into a pixel, and the pixel color depends on where it appears in depth. The program came up with these sorts of gradients which I was not expecting, but it makes sense since the geometry is mapped from top to bottom.

The program can reconstruct the 3D file from the PNG as well as transform a 3D file into a PNG. The encrypted outcome is so different that you could bypass copyright. Nobody could look at that and see Mickey, though a computer could.

It’s interesting that we still think of images as something that are only for humans to read but in reality they’re for machines as well. The images are structured in a standardized way so that any computer can open it and make sense of it.

AS: So could they eventually develop a means of screening for these images?

MPF: Not really – they would have to screen every PNG on the internet, and there are too many images already. I like that PNGs are already so shareable, there is already an infrastructure for sharing images, that we could now use for sharing 3D files.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: SpongeBool, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 47 x 13 x 40 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: SpongeBool, 2015, SLS polyamide, resin, paint, 47 x 13 x 40 cm // Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de, courtesy of NOME

AS: Many of your projects attack copyright laws, which, as you have pointed out before are used to protect profits, not enrich culture. How can we find a balance between openly being able to use cultural materials and at the same time compensating the creators for their work?

MPF: I think it’s important that copyright is not treated as a one-rule-fits-all scenario. I like that the Creative Commons empowers people to choose how they want their objects, or which parts of them, to be copyrighted. 3D printing is still undecided in terms of copyright. People are still deciding whether or not you could copyright a 3D file, and I have lawyers contacting me sometimes to know my opinion.

Exhibition

NOME

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez: ‘Hard Copy’

Exhibition: Nov. 06 – Dec. 23, 2015

Dolziger Straße 31, 10247 Berlin, click here for map