Interview by Alison Hugill in Berlin; Wednesday, Dec. 23, 2015

Berlin-based, Scottish artist Katie Paterson has been collaborating with scientific research institutes and space agencies for several years, to realize complex projects that consider disciplines like astrophysics from an artistic point of view. An ongoing work, initiated in 2014, is one of her most ambitious time-based projects: the ‘Future Library’ is a forest planted in Norway, which in 100 years will produce the paper necessary to publish a special anthology of books by famous authors. Paterson and the authors will not live to see the library come to fruition, but the piece has far-reaching consequences that push us to think about books not merely as consumer objects but also as deeply connected to our planet. Many of Paterson’s works have these kinds of effects, merging the poetic and the scientific into contemplative and profound conceptual projects. We spoke to Paterson about her nomination for the recent PIAC prize and her upcoming projects.

Margaret Atwood and Katie Paterson // Photo © Giorgia Polizzi, Future Library is commissioned and produced by Bjørvika Utvikling, managed by the Future Library Trust. Supported by the City of Oslo, Agency for Cultural Affairs and Agency for Urban Environment.

Alison Hugill: Our topic for this month is the crossover between art and science. Your work is very scientific in a lot of ways. How do you collaborate with scientists and research institutes, and what effect does your role as an artist have on that interaction?

Katie Paterson: I’ve undertaken artist residencies in scientific institutes – University College London Astrophysics; the Sanger Institute in Cambridge and worked with cosmologists at CALTECH, W.M Keck Observatory; NASA, and recently the European Space Agency. I’ve worked with lighting engineers, geographers, geologists, perfumers, biochemists, technologists, biologists, horologists, foresters, palaeontologists and others. These interactions are always unique and in relation to the idea at hand. The collaborations range from discussions, sharing ideas and knowledge, to very practical input. For example NASA shared with us their recipe for the scent of Titan, Saturn’s moon, which was used as a layer in my outer space candle. Astronomers at UCL have helped my studio determine the time on other planets to an extremely accurate degree, for the

Katie Paterson: Campo del Cielo, Field of the Sky, 2012 // Photo ©MJC, 2012

Commissioned by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

Meteorite launched into space aboard the ATV, 2014 // Photo © ESA, 2014

AH: Where does your interest in astronomy and astrophysics come from?

KP: Most directly from a period living in the remote north in Iceland, which opened up a connection to the sky and beyond, seeing the earth as a seething planet alive with boundless energy, one of many millions of others. It took being in the remoteness of this extraordinary landscape to activate this encounter. More indirectly, from a thirst for the unseen, the unknown. The depth of time and space provides a link to vastness, a reciprocal encounter with the beyond that I find nourishing and imaginative. Astrophysics probes at the limits of the known, the limits of language and a kind of abstraction that allows a breaking out of rational thinking for me: for example looking directly at a time where the earth didn’t even exist. Particles at two opposite ends of the observable universe interacting. A black hole singing.

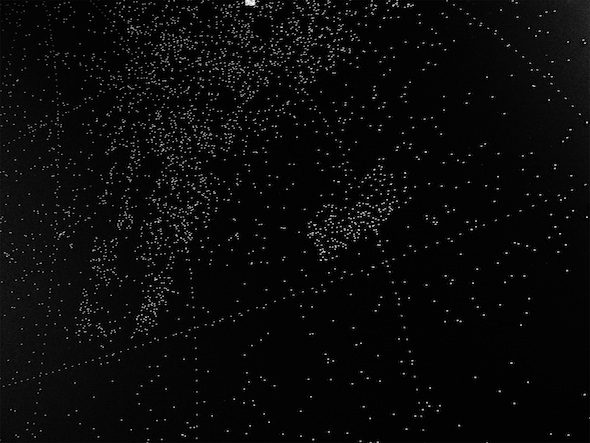

Katie Paterson: All the Dead Stars, 2009, Laser etched anodised aluminium, 200x300cm // Photo © Katie Paterson, 2009, Courtesy of the artist

AH: Many of your works are time-based and durational, and you may never see the results of them yourself. Can you talk about your interest in time as a medium or material for your art?

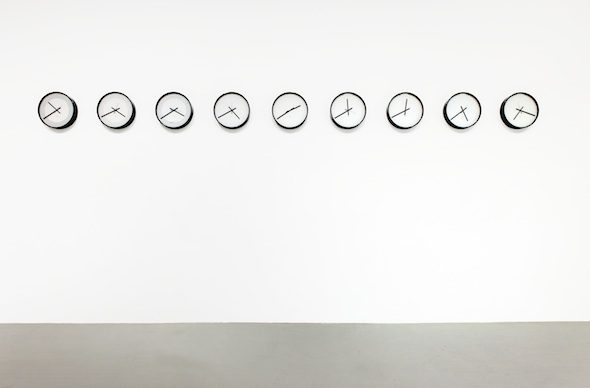

KP: Time runs through everything I make. From the time of a short phone call to a glacier to the centuries of its demise; the time for the light from a dying star to pass millions of years through space to reach our eyes. A circle of beads encompassing life and death through geological time. The time on Venus ticking away on a set of station clocks. A forest growing for 100 years to become a book, unread until then. A 12-hour candle burning through a journey from planet to planet. A nano-sized grain of sand lost in the depths of an ancient desert. Why I’m drawn to time is hard to describe – it’s to do with being outside myself, and being inside a more universal network where distance and time might not necessarily even exist.

Katie Paterson: Timepieces (Solar System), 2014 // Photo © Blaise Adilon, 2015, Exhibition view Frac Franche-Comté

AH: Your piece ‘Campo de Cielo’, recently nominated for the PIAC, has quite a poetic or romantic impetus – to return the meteorite back to space. A kind of homecoming. How do you wed your interests in these kinds of poetics with scientific inquiry?

KP: They overlap by nature. One of the cosmologists I work with is searching for the first star to have evolved in the universe. To me that’s entirely poetics combined with scientific enquiry. Though if I tried to imbue any of my works with poetics, or scientific enquiry, it would collapse.

Katie Paterson: Light bulb to Simulate Moonlight, 2008 289 light bulbs, 28W, 4500K // Photo: © Haunch of Venison, 2010, Courtesy of Haunch of Venison, London

Katie Paterson: Light bulb to Simulate Moonlight, 2008, 289 light bulbs, 28W, 4500K // Photo: © Ingleby Gallery, 2011 Courtesy of Ingleby Gallery

AH: Tell us about the projects you are currently working on.

KP: I’ve been working on ‘Hollow’ for nearly 3 years and it’s launching in 2016, in Bristol, UK. It’s a collaboration with architectural studio Zeller & Moye. We are building a structure made entirely of the world’s tree species. Over 10,000 different species of tree will be contained inside. It’s a gigantic project that’s involved a great deal of research, and an archival, cataloguing process that definitely overlaps with a scientific approach: we have effectively been building a Xylarium, a library of wood. When visitors enter ‘Hollow’, they will encounter an immensity of clusters of shards of wood from every country and every family of tree on earth, which we hope will transport them across the globe, through time, space and evolution. ‘Hollow’ will be a kind of forest of every forest, a microcosm where the natural world is collapsed into one. I am also working on my first monograph, and a book of ‘Ideas’ (works to take form in the imagination); and two new pieces involving solar eclipses and constellations. ‘Future Library’ will continue for my entire life.

Exhibition Info

GARAGE ROTTERDAM

Group Show: ‘Hemelbestormers’

Exhibition: Dec. 4, 2015 – Feb. 14, 2016

Goudsewagenstraat 27, 3011 RH Rotterdam, click here for map

Writer Info

Alison Hugill has a Master’s in Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on marxist-feminist politics and aesthetic theories of community, communication and communism. Alison is an editor, writer and curator based in Berlin. alisonhugill.com