Article by Alice Bardos in Berlin; Monday, Dec. 28, 2015

Clemens von Wedemeyer, A Recovered Bone, 2015 // Courtesy of KOW

Clemens von Wedemeyer’s latest exhibition at the KOW – Cast Behind You the Bones of Your Mother – is inspired by Greco-Roman mythology, but is brought to life through various new forms of technology such as 3D printed sand. In Ovid‘s Metamorphoses, Deucalion and Pyrrha were the two lone survivors after a flood and are advised to throw their mother’s bones behind them. Their interpretation of this is to use the stone of Mother Earth as the bones. The narrative is insightfully tied together by Clemens von Wedemeyer, through reflexivity, technology, mortality and politics in his eclectic use of film, sound, sculpture, and audience curation.

Alice Bardos: What was the inspiration behind this project, and how did your idea evolve?

Clemens von Wedemeyer: It’s based on the show I had in Rome, Italy at the MAXXI museum in 2013. I produced a couple of works based under this umbrella of The Cast and it’s all centred around this idea of sculptures and acting. It’s all about how materials come to life. For example, how people praying to a statue in a church animated it. Some of those ideas from Rome, I am now revisiting with this exhibition and I have just enlarged or modified a few pieces, and even incorporated new ones which include sculptures.

AB: Many of your pieces, such as ‘A Recovered Bone’ (2015) were produced through 3D printing, in what ways do new technologies allow you to explore your artistic visions?

CvW: In Rome I made a film called ‘Afterimage’ (2013) which is based on a three-dimensional scan of a space in Rome – of the building workshop in Cinecittà, where they stored the props they had been using for ninety years from film sets. With this scan I could make a film, a print or, even produce a holodeck. Here in Cast Behind You the Bones of Your Mother, I printed objects from sand that fit a story that is being told through sound. 3D scanning technology is used by architects and archaeologists to capture the dimensions of a space which can later be animated on a computer.

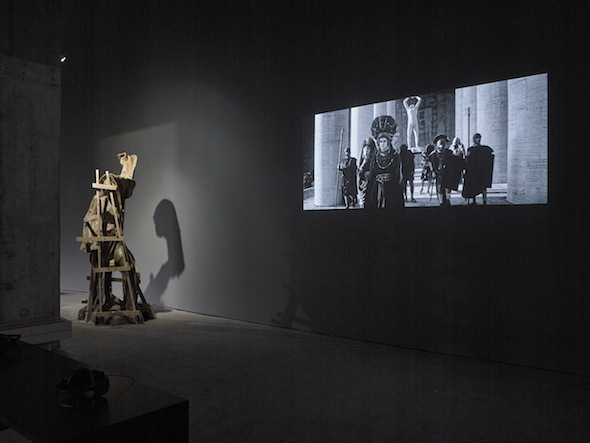

Clemens von Wedemeyer, Pyrrha Rest Form & The Cast: Procession, 2013 // Courtesy of KOW

AB: You’ve had various exhibitions abroad, how have international politics influenced your work?

CvW: In one of the featured films, The Cast: Procession (2013), there is a scene from the fifties that is re-enacted, in which extras started demonstrating against a movie production of Hen Hur (1959) at Cinecittà, in order to get their money back after having been scammed. I don’t try to produce inherently or obviously political works, instead I like to inspire viewers to uncover the political dynamics on their own, and according to their previous experiences. When I made the film The Beginning in 2013, contemporary parallels could be drawn. You could connect its themes to what was happening in Iraq and Syria. Or even earlier in Afghanistan when the Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The film is really just meant to inspire people to think about what drives a person to build and destroy sculptures.

AB: Many cultures seem to have a profound historical connection to the worship of sculptures, which is a key theme here. Why do you focus on the antiquity of Rome and Greece?

CvW: My choice to focus on these cultures, was because my initial inspiration for these works happened when I was in Rome. It’s also quite well known and aesthetically apparent, that the Romans were inspired by the religious and artistic practices of Greece. Secondly, I am interested in film – and for example, for this project I drew upon forty to fifty films from the North American and European production in the twentieth century, and ancient Roman and Greek culture is well represented in this medium. I found their concern for the relationship of people to their sculptures to be inspiring. These films reveal an underlying human subconsciousness in relation to human figures.

AB: Is your connection to the sculptures in your works personal, or about your opinion of society?

CvW: The development of the story is full of destruction and iconoclasm of films from the twentieth century really fed well into my own personal cinematographic style. I am also personally fascinated with how fiction comes to life. To me it’s interconnected with how belief comes into life and becomes fundamentally attached to tangible objects.

AB: In keeping with these themes, do you think that the belief that people invest in the tangible, in sculptures is inherently good or bad?

CvW: You can see a loss of history.

Clemens von Wedemeyer, Cast Behind You the Bones of Your Mother, 2015 // Courtesy of KOW

AB: Do you find yourself to be inspired by Germany’s particular history of industrialization, and those who reflected on it? For example The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction by Walter Benjamin.

CvW: Of course Walter Benjamin is important for me. When you think of the overlaying of historical layers, and his theories, they can be very inspiring for an artist when it comes to the topic of how memory works. Secondly, I drew a lot from his ideas for the making of ‘Procession’ (2013), when he described the angel of history, the Angle Novus – which is a character who flies back from paradise because of the force of an impending storm. The storm represents progress. He was caught by the storm facing backwards, but was sent soaring in the opposite direction toward the future. His text is inspired by Klee’s pieces entitled ‘Angelus Novus’.

I was inspired by this trope of going into the future facing backwards – always looking in the rear-view mirror so to say. So I came up with the idea that the camera should always move backwards, which is really interesting because then viewers have a more interpretive role, and can predict scene by scene, what might happen next – it’s more immersive this way.

AB: Why did you choose to reproduce Stanley Kubrick’s bone tool from the film “2001: A Space Odyssey” as humans’ earliest technological development. How does your reproduction respond to the original?

CvW: When you see the film you cannot see where the bone lands, and I asked myself, where could it have ended up. It doesn’t fall down because it turns into a spaceship. I heard about the technology of being able to create a three-dimensional form from a revolving object on film. You can even take photos around yourself and then turn yourself into a 3D figure. In the film, the bone revolves so this inspired me to explore whether it would be possible to reproduce it through these means – in asking a computer to render the form. I tried it, and the computer made a lot of mistakes, actually. But I was excited instead of disappointed by them. For me the bone actually came to look like a mix between a real bone and the spaceship.

Clemens von Wedemeyer, The Beginning. Living Figures Dying, 2013 // Courtesy of KOW

AB: With these unanticipated and yet celebrated hiccups that the computer produced, how does this affect your feeling about artistic ownership of the piece?

CvW: Well I heard that Stanley Kubrick actually still has the original bone, and used it to threaten the film producers should they produce a series from his film, he wrote in a letter that he would shove it up their asses. But, apparently, this bone is a gesture, for me the dimensions and ownership of the bone are not an issue, a new bone is here now and that’s all that matters. Well I never imagined that only half of the bone would be created, but I would have been equally excited, however it would have turned out.

Exhibition Info

KOW

Clemens von Wedemeyer: Cast Behind You the Bones of Your Mother

Exhibition: Dec. 19, 2015 – Feb. 27, 2016

Brunnenstraße 9, 10119 Berlin, click here for map