Interview by TL Andrews in Berlin // Tuesday, Mar. 29, 2016

Ato Malinda’s work as a performance artist and activist has been featured at venues like the Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, the National Museum of African Art and the Smithsonian. She is known for tackling themes of sexuality and post-colonial politics in a Kenyan, and broader African, context.

One of her performances, ‘Mshoga Mpya’ (The New Gay Kiswahili, 2014) for instance, was created as a response to the legal ban on homosexuality in Kenya. In it Malinda actively breaks down the anonymity and publicness inherent in performance art by sitting in a black cubicle that only one viewer can enter at a time. Once visitors move into the space she relays stories from the LGBT community in Nairobi. Intimacy imbues the anonymous voices with a sense of privacy, while at the same time forcing visitors to grapple with the larger significance of the stories.

In ‘Mourning a Living Man’ (2013), Malinda tackles memories of her dysfunctional childhood home, candidly addressing child abuse and commenting on themes of gender performativity through the use of color and language. We spoke to her about her conception of home and how it has impacted her work.

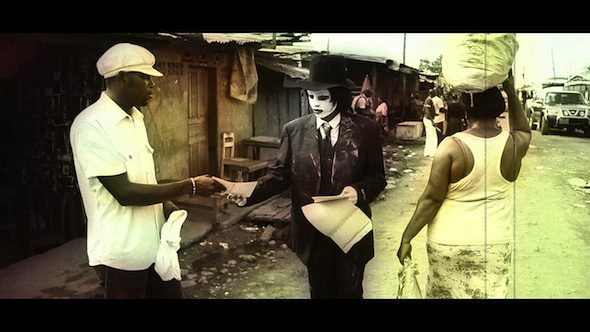

Ato Malinda, Papai Wata: Film Still from ‘On Fait Ensemble’ (2019) // Copyright Ato Malinda

TL Andrews: What do you see as the link between geography and identity, given that you have lived in such different places? And do you think an artist’s origins obligate them to tackle particular issues in their art?

Ato Malinda: In the first twenty years of my life I had lived for a significant time on three different continents. One of the things that struck me growing up, was the commonalities between people. There were cases where a teenage girl in Kenya was not so different from a teenage girl in the Netherlands, or in Texas for that matter. The specifics might have been different but in general each girl was experiencing the same thing. Class may be a determinant factor in these common life experiences, but it is what I experienced. So I think the link between geography and identity may have to do with class and globalization in the last thirty or so years.

I don’t think that an artist is obligated to comment on issues surrounding her country of origin. I feel that there are all kinds of artists in this world and each is called to create in their own specific way. Who is anyone else to tell them what topics to confront, if any at all.

TLA: In ‘Mourning a Living Man’ you addressed very personal issues in a public space. How do you approach exploring such personal issues in the public gaze?

AM: Yeah, I have to be honest, that was a very difficult work to make. At the time, that was what I was going through and I didn’t know of any other way to process it other than to make work about it. That work is about child abuse and I feel now, because of where I am now in my life, I can discuss child abuse without being so personal. I say this because, as it is coming to light now in a lot of news reports, child abuse is very common and lots of people have had to endure what I endured. I think that if I were to tackle the subject again I would do it from a broader perspective to avail the work to a wider audience.

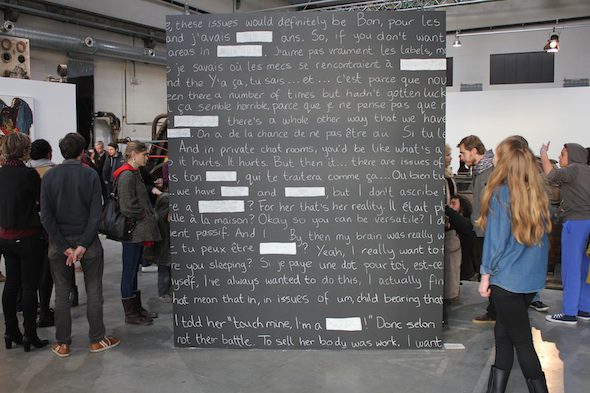

Ato Malinda: ‘Untitled derivative of Mshoga Mpya, or the New Homosexual’ (2014) // Photo by Stu Reigeluth, Copyright Ato Malinda.

TLA: You look at both the way Africa is represented by the West as well as political struggles facing the LGBT community within Africa. In so doing audiences begin to see you as a spokesperson for Africa. How do you feel about being thrust into that role as an African artist, and how is it different for artists from elsewhere?

AM: I am from one of the countries on the African continent and I have made work on a small group of queer-identifying people in Nairobi. I think it is important to clarify that this work does not represent the whole African continent. But, you are correct, I do work on correcting this unitarian view of a dark continent.

Ato Malinda: ‘Untitled derivative of Mshoga Mpya, or the New Homosexual’ (2014) // Photo by Stu Reigeluth, Copyright Ato Malinda.

There’s a professor of African descent named V.Y. Mudimbe. He works at Duke University in the US. He’s written many seminal texts, but one that is apropos is titled, ‘African Art as a Question Mark’. He talks about the process of acquisition of objects from the African continent and how they then got repositioned as African art in Western museums, when in fact on the African continent they had more functional values and perhaps very different aesthetic qualities. This is significant to me because I see a link between this creation of an African art narrative and myself and others being called only African artists. There seems to be a propagation of a binary narrative of us and them both in the earlier acquisition of objects and the terming of contemporary artists as specifically African. Why should there be any difference between us and others? Do we not create a poetic just like any other European or North American artist? I believe we do.

TLA: Through the use of space you manage to maintain intimacy in your performances. Why is that important to you?

AM: I started doing closed performances because I felt like it was becoming too easy for audiences to be complacent with lots of sensational art and events in the world today. I feel like the audience also has a responsibility to be part of a performance. Usually in a conversation with only two people, both of those people tend to pay more attention to each other. Both in ‘Mshoga Mpya, or the New Homosexual’, and ‘Untitled derivative of Mshoga Mpya’ I created space that detracted from other audience members so that one person could really experience the work with minimal distractions. The reactions I got were a complete range from crying to laughing, which made them difficult but rewarding works to perform for me.

Writer Info

TL Andrews is a multi-media journalist based in Berlin. He produces features for radio, television and print outlets with a focus on Berlin, Germany and European themes.