Article by April Dell in Berlin // Monday, Mar. 28, 2016

The latest group show at nGbK in Kreuzberg declares with its title that ‘Father Figures Are Hard To Find’. In reality, so-called father figures can be found everywhere in the heteronormative, nuclear family-based, fatherly role models that populate Western mainstream media. However, this exhibition proposes alternative roles and identities for real and imagined father figures, rewriting histories and genealogies, and redefining what our paternal role models can and should be.

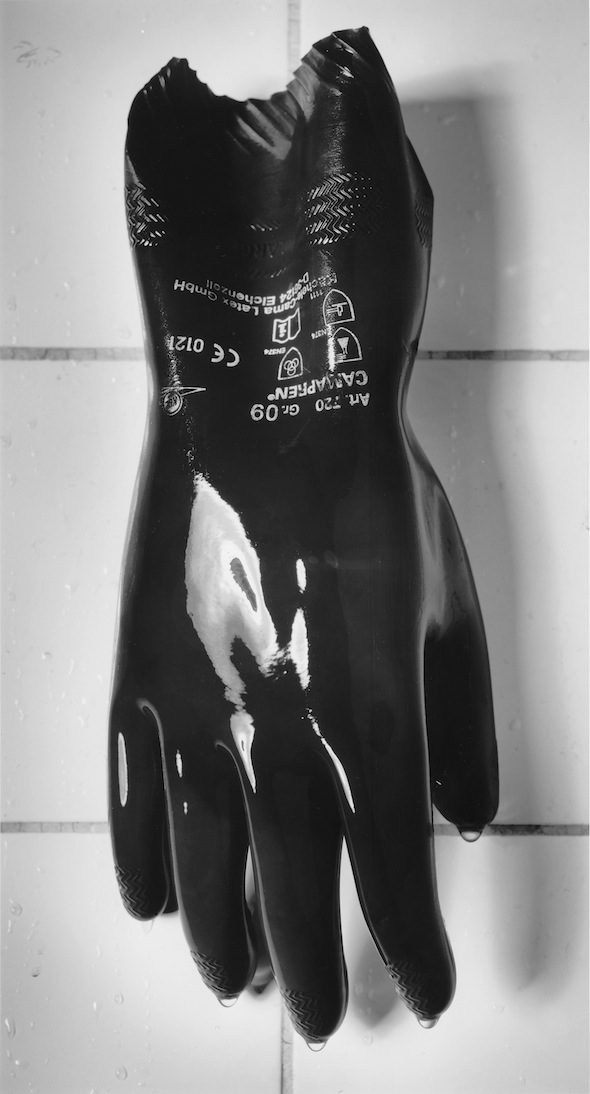

Bodo Schlack: ‘Working Class Hero’, 2007 // © Bodo Schlack

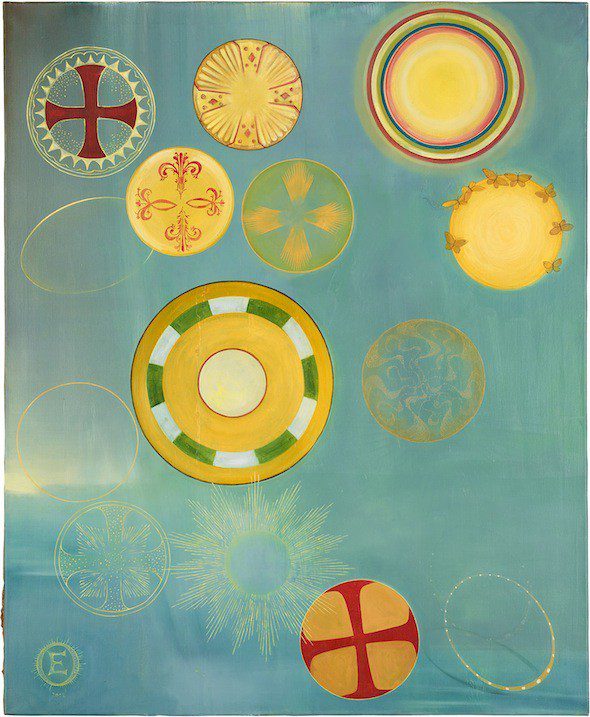

Many of the twenty-plus works in the show reference in some way a persona from the gigantic pantheon of canonised father figures: of religion, of celebrity, and of art history. Aleksandra Mir’s collage compares a team of American astronauts to a group of Byzantine Christian saints, suggesting a historical precursor for the ‘National Hero’ father figure archetype. Naama Arad’s wall-sized image of Mount Rushmore similarly picks nationally sanctioned paternal figures tied up with American national identity for scrutiny. The term father of modern art and ones like it are channelled throughout the exhibition as iconic male artists are frequently referenced. A model of Robert Rauschenberg’s design for the BMW Art Car series introduces a lineup of pop-art fathers – Warhol, Lichtenstein, Hockney, Koons – whose designs also adorned the race car series. Egle Otto’s painted work emulates halo icons from the list of painters across centuries of art history that gives the work its name, from Botticelli to Max Ernst. It is a homage to the greats and at the same time undermines them with faked signatures on the back of the canvas. Otto’s final composition is reminiscent of early abstract painter Hilma af Klint in an unmistakably deliberate choice of a woman painter for her model. Otto brings attention to the gendered lens of art history and art criticism, pinpointing a strong critical current in the exhibition.

Aleksandra Mir: ‘Astronaut #09–054’, 2009 // © Aleksandra Mir

Egle Otto, Botticelli, Giotto, Grünewald, da Vinci, Mantegna, Rosetti, Ensor, Parmigianino, Lippi, Raffael, van der Weyden, Ingres, Ernst, 2012 // © Egle Otto

Father as a gendered term is under examination in many of the works. Like Otto, Heike-Karin Föll offers a notable female cultural icon as a potential father figure. In her texts, formed with found plant matter, she spells out the names of queer theorist and activist Douglas Crimp alongside artist and influential Rolling Stones groupie Anita Pallenberg. The fantastical self-portraits by Juliana Huxtable present figures that exude power and spiritual energy. From kitschy religious poster aesthetics to fantasy sci-fi figures, the portraits are not explicitly feminine or masculine but rather move between or outside of gender tropes.

Juliana Huxtable: ‘Lil’ Marvel’, 2015 // Courtesy of artist

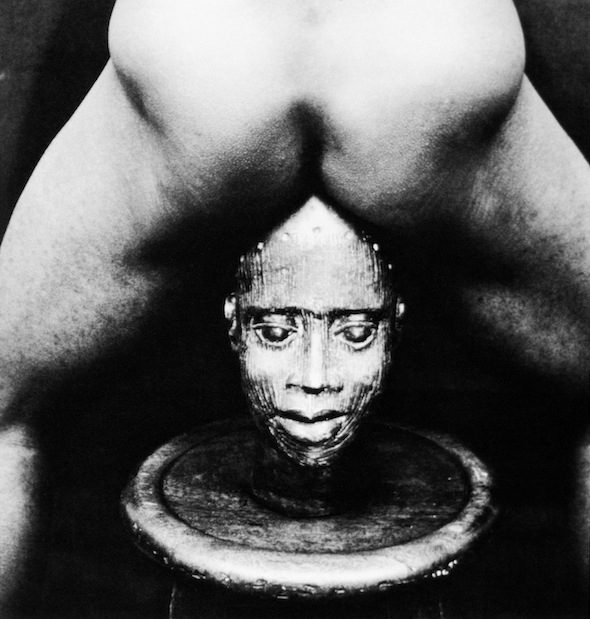

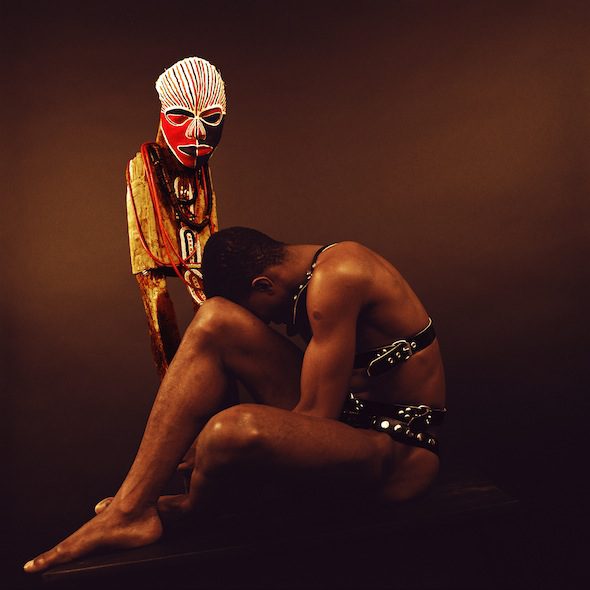

Diverse sexual identities for potential and imagined father figures are another of the shows theoretical pivot points. The curators and artists work to show that fatherhood is not limited to an image of masculinity, nor one of domesticity. Subverted masculinities are presented in several works, including the homoerotic subtext of Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s sensualised photographs featuring the male nude and motifs from Yoruba culture. The shiny black latex glove in Bodo Schlack’s photograph ‘Working Class Hero’ takes on an almost explicit BDSM reference in this context. The sexualised identities associated with the title ‘Daddy’ are also incorporated here as an alternate concept of what a father is or can be. Dividing the gallery space is Lukas-Julius Keijser’s large denim curtain, printed with ubiquitous pop culture slogan ‘Daddy’s Little Princess’. The slogan can be read as a statement of queer self-representation and the curtain as symbolic of a hidden or sidelined community, a curtain behind which an abundance of alternative father figures can be found.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode: ‘Bronze Head’, 1987 // © Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Courtesy of Autograph ABP

Elsewhere in the exhibition works that draw from the artists’ real relationships with their fathers explore the complexities of family connections. A work by Sarah Ancelle Schönefeld and her father Oskar Curter employs a medical drip filled with antipsychotic medication. The liquid intermittently falls onto a plate of water with a projection of Curter playing the flute in his home on it. The result is an image on the wall that is periodically disturbed and ripples like a distorted dream, perhaps alluding to the filtered image children have of their own parents. Konrad Mühe attempts to reconcile the mediated image of his father, the late actor Ulrich Mühe, in his jauntily edited interview pieced together with footage from his father’s acting career. Bridging the gap between public and private personas, Mühe fabricates an intimate depiction of his father from the found footage, begging the question: can the resulting impression be truthful?

Rotimi Fani-Kayode: ‘Nothing to Lose IX (Bodies of Experience)’, 1987 // © Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Courtesy of Autograph ABP

‘Father Figures Are Hard To Find’ is at once critical of art historical and pop culture patterns of gender stereotypes and inequalities, while at the same presenting a positive conclusion that alternative father figures are out there if you look for them. You can pick your own role models, you can write your own genealogy, and rewrite art history. Running until April 30th the exhibition hosts a full schedule of events including live performances, lectures, and guided tours.

Writer Info

April Dell is a freelance writer living and working in Berlin.