Interview by Alison Hugill // Apr. 19, 2016

Yishay Garbasz is a Berlin-based artist and photographer whose diverse body of work displays a fortuitous congruity. Often, her subject matter is trauma and its intergenerational inheritance, through which bodily and embodied sites of conflict and memory loom large. In the case of her 2010 tour-de-force, ‘Becoming’, which chronicled changes in her body over the course of her gender affirmation surgery, she created a human-scale zoetrope to exhibit the work. When we spoke over tea in her Mitte apartment, Garbasz’s fierce intersectional feminist standpoint and concern for the plight of trans women worldwide came through as crucial to her art practice, as well.

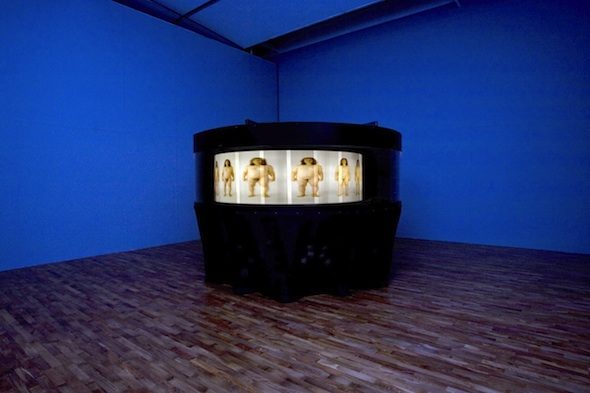

Yishay Garbasz, Becoming, 2010, Installation of becoming at the Busan biennale // Copyright Yishay Garbasz, Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Art New York.

Alison Hugill: Let’s talk about your 2010 piece ‘Becoming’.

Yishay Garbasz: The piece looks at the viewers’ reactions in a way. In the beginning most people look at the genitals—yes, no—but then they continue to look. The most interesting part about the piece is the hair. There are two versions of the work: the zoetrope, which when it was installed was the second biggest in the world, and the flip-book version. Even in the flip-book, the hair is really what interests people. The genitals occupy so little of the body in terms of percentage, and the legs and arms don’t change. I’m the same person that I always was. To put it more clearly: I’m the same woman I always was. I wanted to bring that to light because the before-after trope is boring and clichéd, contrary to what hundreds of CIS photographers would have you believe. I wanted to create something more real, and not about before and after.

AH: Is there a difficulty in being both the photographer and the subject matter of the work?

YG: The practice is very different. This was a very regimented project: I had to do it every weekend, except for about a month when I was too depressed to do it. Every weekend I would take a picture. When I was feeling very cheerful about it, then sometimes twice a week. It’s not about going outside and doing stuff like my usual work, it’s about returning time and time again and watching the drama your mind creates with this repetitive task. That’s what was really interesting for me as an artist.

AH: The repetition comes across for the viewer as well, in the way that you have chosen to present the work.

YG: Firstly, I am very neutral in my body: I am not trying to make myself less pretty or more pretty. I’m very matter-of-fact about it. The second thing was the size of the zoetrope. I was very particular about the size because of the context of Victorian pornography. I didn’t want to make it too small because that changes the power dynamic. So I had to make it large. I wanted the power relationship with the viewer to be correct. When you have a 1-metre high image size, and the zoetrope is made of half a ton of steel, a quarter of which travels at 11km per hour (12 frames per second), it creates a correct power relationship. The viewer doesn’t have to stay but if they do there is a very interesting relationship going on between the object and the viewer. It’s viewable from any direction. There’s something about the massiveness and the movement. I didn’t want to make a projection because it’s very unreal.

The easiest way would have been to inkjet on the plexi but I actually used photographic reproduction. We used 24 pieces of scotch tape because the engineer researched and found it had the right heat-resistance. We also had to consult with a couple physicists. The steel team was five ship builders. It was a very big project, not a trivial undertaking.

AH: Is there something in the cyclical nature of the zoetrope that changes the power dynamic as well?

YG: The circle has four frames of grey to show that it’s not cyclical. It’s just my body. It’s all about the change and the not-change, in the same stroke. But again, the hair was the main focus. Having people be more than the sum of their genitals, I think, is a big win.

AH: That brings us to another work of yours, ‘Eat Me Damien.’ In that case you bring the genitals to the fore, but as a point of critique.

YG: Mostly it’s not about gender. It’s about the jerky male art thing, which infuriates me. After my surgery I kept the genitals, I knew I’d do something with them. There were several options: a door-knocker for a female divorce lawyer (‘Yes I am that good’) [laughs] and also floating them like basketballs.

‘Eat Me Damien’ won because the title became the favourite one. I think the critique is obvious: there is this predatory, business-oriented, professional artist syndrome.

AH: So how is it not related to gender? You also see women artists in this role?

YG: It’s like Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire: Fred is the famous one but Ginger had to do everything he did but backwards and in heels. This is how it feels. As a woman artist, I have only 10% chance to be in an exhibition here in Berlin. As a woman with an experience of trans I have 0% chance. Even when there’s a trans show there are no trans women, or maybe a single token trans woman. When the Historisches Museum did their thing they didn’t have a single trans woman: they had images of trans women. The Schwules Museum right now has a show about trans women but I don’t have a chance to exhibit. The closest you can see my work to Berlin, where I’ve been living for 8 years, is New York or Korea. Closest I’ve talked about gender is the Tate Modern.

Yishay Garbasz: Eat Me Damien, 2010, Installation view, Have We Met Before? 2012 // Photo by Varvara Mikushkina // Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

AH: In that kind of climate in Berlin, what keeps you going?

YG: I’m really stupid and stubborn. I live here in Mitte, my mother grew up on Linienstrasse two streets away. I’m stubborn. There is something for me here.

AH: You exhibited ‘Eat Me Damien’ at the Seven Miami fair and in New York in the group show Have We Met Before?.

YG: Yes, the show in New York was of old generation and younger generation artists dealing with the body. I was in an exhibition with Hannah Wilke. I met her husband who took the last photos of her sitting. There was Andy Warhol, Man Ray, Chris Burden…

In Miami, I showed four different pieces because it was very important for us to have context. ‘Eat Me Damien’ is a very strong piece, so it is important for people to have context. Some people will just fixate on the testicles and not take the next step.

AH: Is providing that context more work for you, beyond the role of the artist and entering the realm of educator?

YG: It’s not my job to educate. My job is—when I do a solo exhibition as an artist—to show the viewer how to look at my work and how to move in my space. That’s my responsibility as an artist. I need to know who my audience is: I do height distribution, I do age and size, because sometimes it’s very critical. I will figure out the average height of the viewer in whatever country I am in, for the viewers that I will get.

If the location is young and trendy I have to look at the attention span. If it’s shorter I have to see how I can play with that. That’s my responsibility as a artist. But to explain gender: fuck that!

At the fair in Miami, lots of people came just to see ‘Eat Me Damien’. My gallerist Ron Feldman wanted to get it in the show in New York to look at it in generational context as well. We had Lynda Benglis with her incredible Art Forum double-headed penis. There was an incredible amount of art to give the right context. ‘Eat Me Damien’, ‘The Number Project’, and ‘Becoming’ were all together in this show.

AH: You seem to have an overarching theme that emerges in your work.

YG: Mostly, I deal with trauma. People think that their voice as an artist is somewhere far away, over some obstacle: for me it is right where you stand. What you’re facing right now, is your voice. The obstacles are where your voice is. I don’t think about the trajectory of my work it just happens that way. In retrospect it looks thought-out but it’s not. I’m clear enough in my mind and my heart that these things are just there.

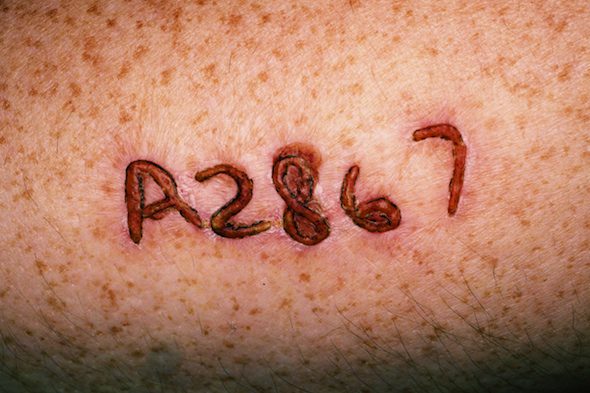

Yishay Garbasz, The Number Project, 2011, Video Still // Copyright Yishay Garbasz, Courtesy of Ron Feldman Fine Arts, New York

Yishay Garbasz, The Number Project, Close Up Day 9 // Copyright Yishay Garbasz, Courtesy of Ron Feldman Fine Arts, New York

AH: In ‘The Number Project’ you literally inscribed your mother’s trauma onto your body, her number from Auschwitz.

YG: The reason I carried it was because she had it removed. She had a scar from plastic surgery when they removed it. She couldn’t talk about it and part of my work, dealing with my own trauma, was being able to talk about it and create conversations. I didn’t want to take away from the image of the Auschwitz tattoo like some other artists. I don’t want to recontextualize it, it’s a bad thing to do. I wanted the number but I didn’t want the tattoo.

After lots of research I learned about a branding technique. You can see the blow torch right here. The hardship wasn’t the pain so much as the psychological inhibition of doing it to myself. For the first month I had a hard time even looking at it. In the second month it became a comfort, because I could feel it. It’s almost all gone now but it will never be gone.

Originally, I wanted to take three pages from the Auschwitz death book and brand each number on different people, so the people who died are carried today so we can reconnect. Many of my German friends wanted to do it. But the act of branding is so intimate and so vulnerable that I couldn’t do it to somebody I wasn’t close to. One close friend was branded with my grandmother’s number, though.

AH: What projects are you working on now?

YG: I just finished an anti-racism project in Japan. I was working with my friend Yumi Song and we were talking about how, during the Second World War, everybody knew that the Koreans poisoned the water in Japan. And still now everybody knows that the Koreans caused 3/11 – the tsunami in Fukushima. Hold on: we all know that the Jews are the ones who poisoned the well, we are the ones who drink the blood of babies. Our project became trying to create stereotypes or projections. So we went around and poisoned a lot of stuff using chilli peppers. We made videos and still which will be shown at the beginning of next month in Kyotographie Plus.

Most of what I do as an artist is write grants. I’m also working on two books: one about the trauma from Fukushima and one, through a Japanese publisher, about the show ‘Do What I Say or They Will Kill You’. This one looks at Israel/Palestine, North and South Korea, and Catholic and Protestant in Belfast. I look at these types of fences as a psychological aspect. Every side that has built them has not won: why are they still being built? Belfast is so interesting: most of the “peace lines” were created after the Peace Agreement. Why would they do that? Same with Israel/Palestine. This is where it helps to be queer: it’s about othering. The less contact you have, the easier it is to make the other a monster.

Yishay Garbasz, Bikini, Khao Sok, Day 22, 2011 // Copyright Yishay Garbasz, Courtesy of Ron Feldman Fine Arts, New York

Finally, I have to say something about trans murders. This has been a very nice interview but I need to kick someone’s ass. The next project I’m working on has to do with violence, both individual and institutional. Part of the project is about the murder and violence against trans women. In America right now there are several laws enacted that target trans people but particularly trans women. The number of death threats are increasing. The life expectancy of a trans woman of colour in America is 35. In Brazil, it’s 30.

This is where intersectionality comes in: feminism is not just about one thing. We have the ‘white feminist’ thing which excludes all women who are marginalized, of colour, with disabilities, with a history of trans, sex workers. All that is excluded: we focus on one issue, but that’s how we become separated. This is a big problem I see, not encompassing all issues together. Trans women–because trans men, especially in the art world, are more well-represented–are a big part of that. There’s a lot of work by CIS artists, photographing trans people, but if I do it I don’t get the funding. The subject has already been covered. A lot of curators and institutions are lazy. They are interested in showing what they feel comfortable with.

AH: So the solution is a total structural overhaul?

YG: It’s a personal overhaul, being able to step out of your comfort zone. But it’s also an institutional critique: give me a sledgehammer!

Artist Info

Writer Info

Alison Hugill has a Master’s in Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on marxist-feminist politics and aesthetic theories of community, communication and communism. Alison is an editor, writer and curator based in Berlin. alisonhugill.com