Interview by Alison Hugill // May 20, 2016

Romeo Alaeff is a Berlin-based artist from Brooklyn, New York. His zoomed out photographs of cityscapes, intricate detail drawings and abstract paintings all deal with a common theme: the many manifestations of security and control in our urban landscape, as well as the attendant sense of insecurity or fear motivated by a heightened emphasis on terror and intimidation.

Alaeff originally studied biomedical engineering and mathematics, and his interest in scientific inquiry from an artistic perspective led him to found ‘Lines & Marks’, a publication dedicated to the role and practice of drawing across the arts and sciences. We spoke to him about his series ‘Insecurity’ and ‘Life During Wartime’.

Romeo Alaeff: ‘Alexanderplatz, Berlin, Germany’ // Photo courtesy of the artist

Alison Hugill: Let’s discuss your series called ‘Insecurity’. You look at security apparatuses in Israel/Palestine, Germany and the US. What, from your perspective, unites these states in their use and/or misuse of security controls?

Romeo Alaeff: Though of course it’s a significant part of it, the focus of ‘Insecurity’ isn’t really a comparison of the use and misuse of security controls. Rather I am more interested in the propagation of fear which results in an escalation of security controls or security theater. Or the ways in which security and security theater, in turn, by accident or design, cultivate fear, and how all those things relates to one’s feeling of safety or oppression, or alter one’s behavior in the public sphere.

What unites these countries is that they are all democracies, with radically different political histories and cultures, attempting to balance, with various degrees of success, security with civil liberties. The most extreme example of this can be seen across the timeline of Israel/Palestine, from the clashes between Arabs, Jews and the British, starting under the British Mandate for Palestine, through Israel’s war of independence in ’48, the Suez crisis in ’56, the occupation of Palestinian territories after the Six Day War in ’67, the Yom Kippur War in ’73, the Lebanon wars, two major intifadas, three if you include the current knife intifada, the Gaza wars, and hundreds of terrorist attacks, hijackings, etc.: the Israeli government has steadily moved right in tandem with an escalation of security protocols.

It’s an interesting case because there is probably no other country in the world in which the concept of security is as embedded into the social and political fabric. So much so, that certain aspects of it have become mundane, and therefore invisible. This actually is the most interesting and scary part of the picture for me. In Israel, for example, one has come to simply accept that they will have to go through a metal detector and have their bags physically checked at the grocery store or movie theater, or pretty much anywhere they go. In fact, even if the efficacy of some of the bag checkers is sometimes dismissed by Israelis as simply theater, people are more than willing to go through the motions, and hardly even notice it as strange. I can’t imagine, yet, this scenario in Europe or the US, where going to the grocery store starts to resemble going through the airport, but I do see, with every terrorist attack, or in response to certain types of crimes, a shift towards this model. In no small measure, this is bolstered by the media and politicians who exploit these events for ratings, political gain and societal controls. I think the news is one of the worst inciters of abstract fear, but it’s the politicians that turn fear into public policies. In my opinion, the probable misuse of security controls is a given, however, one must also try to appreciate the very real difficulty of balancing true security needs with freedom of movement and expression. I think that that is one of the most significant problems of our time.

Romeo Alaeff: ‘Joint Task Force Empire Shield. 34th Street/Penn Station Subway, New York City’ // Photo courtesy of the artist

AH: Your photographs often look at the way the city is policed and controlled in various ways. What have you discovered about contemporary city life through your photo series?

RA: I’ve noticed increasingly, especially in bigger cities, that there’s hardly a place that there isn’t a photo opportunity. So many in fact, that I stopped taking certain pictures because they have become so mundane. That fact is a testament to the idea that security is becoming more and more ubiquitous and banal. People are slowly accepting and integrating the various manifestations of security controls into the landscape of public and private life, whether it’s private security, police, the military, the NSA, or whether it’s cameras, barriers, fences, alarms, etc.

There are two ways to look at it. Either one feels safer due to these measures, and they allow for more freedom, or one might feel oppressed or even at risk from security personnel themselves. Ferguson is just one example of this debate on whether one feels safer or less safe due to police presence. The debate on the right to bear arms is another. Or of giving up privacies. From my personal experience, not measured in comparative body count, Germany seems to be the worst regarding an overall feeling of oppression from a sometimes massive police presence. I have a few times been the recipient of aggression from German police and I have actually grown to feel uncomfortable being around them, or even asking them a question, especially when they are geared up, such as during protests. And yes, I am generalizing here. The German police do have to contend with frequent protests and violent elements, ranging from neo-nazis on the right to anarchists on the left, which often clash. But for me, this feeling of oppression is compounded by the the fact that the police do not really allow you to photograph them doing their jobs, which is ironic especially because it is regular practice for German police to carry video cameras during protests and public events. This might be for justifiable reasons from their perspective, but for example, when I photographed a riot police officer holding a video camera, and not his face mind you, only his hands, I was accosted by four officers, yelled at and made to delete my photo. This feels very fascistic but they claim it’s for their privacy and protection, and you can’t really argue with them without fear of them taking your camera or arresting you. I can’t say I fully agree with the justification, as the right of citizens to monitor police trumps that concern, especially for public officials operating in public spaces.

Romeo Alaeff: ‘Apache helicopters over Tel Aviv Beach, Israel’ // Photo courtesy of the artist

In the US for example, there is an opposite trend, where citizens feel that filming police on their cell phones is a constitutional right. YouTube can attest to that. And in recent history, these videos have been used to prove police brutality as well as promote other political agendas. Also ironically, Israel, even with many NGOs actively seeking to prove they are the most immoral army in the world, and of course with its share of abuses, seems to have the most tolerance in relation to the actual daily threat level, and I’ve had the most freedom there photographing security personnel and the military in public spaces. I never had an issue myself, except once when I had a gun pulled on me for photographing a train station security checkpoint. But this was during a two month wave of daily stabbings and the whole country was on edge. And of course, Arab-Israeli citizens and Palestinians have a much higher level of skepticism and fear of being profiled and treated with hostility. But Israel’s situation is the most complex and the threats the least abstract, so all of it on both sides needs to be looked at with this in mind. The IDF and Israeli police collaboration with the Palestinian Authority is an interesting relationship which attests to this complexity. Ultimately, a general feeling of safety in relation to freedom of movement, speech and privacy is what is affected in contemporary city life.

AH: In your series of paintings & drawings, ‘Life During Wartime’, you analyze the risk-society from a slightly more abstract point of view. What kind of warfare are you capturing in these pieces?

RA: The paintings, drawings and photographs all fall under the umbrella of ‘Life During Wartime’ but each deal with the subject of fear and defense mechanisms from different frameworks. Whereas in the photos, I’m very specifically documenting security personnel and physical apparatuses, the drawings and paintings also explore internal warfare. For example, what defense mechanisms does one employ in response to the fear of intimacy, or of failing, or being taken advantage of, of being excommunicated from one’s tribe, or of death? For the last one for example, religion might be the defense mechanism. I’m drawing parallels and making connections between personal fears and defense mechanisms to social and political ones.

The paintings are the most abstract and operate as an almost blank screen onto which the viewer can project their own narrative. I developed a process in which I paint very ghostly monotone watercolor glazes on large canvases and panels. The intent is to imply a situation in which there might be something wrong. The idea is to evoke a slight uneasiness which in part is projected from the viewer’s life experiences, or assumptions as to what is happening.

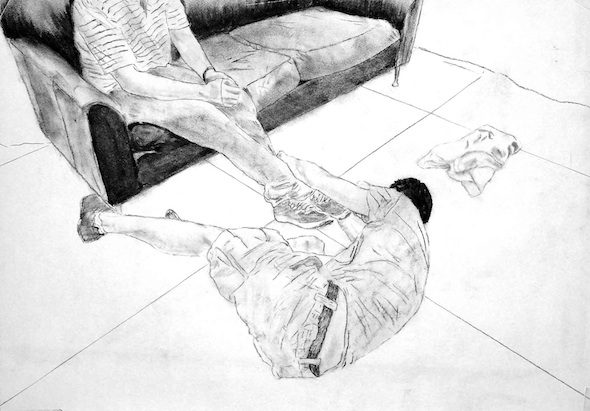

The charcoal drawings play a different role in the work. In the drawings, the exact opposite of the paintings, I can explore very specific scenarios. They are kind of one-frame scenes which together create a narrative, a kind of abstract graphic novel with no words, beginning or end. So along with the photography, I have three ways I am trying to examine the same thing, but by creating different modes for experiencing them.

Romeo Alaeff: ‘Life During Wartime’, Charcoal on Paper, 42×59,4 cm // Courtesy of the artist

Romeo Alaeff: ‘Life During Wartime’, Watercolor on Canvas, 180×240 cm // Courtesy of the artist

AH: Can you talk about some of the cities you’ve lived in and how you see and render artistically their hidden as well as overt systems of control?

RA: I’ve lived in a lot of places in the US and Europe–New York City, New Orleans, Texas, Scotland, Berlin and I’ve spent time in Israel during the first Gulf War and other occasions. It was actually due to my frequent trips from the US to the Middle East growing up that I started to notice a stark contrast between those two worlds. So when I started to see, especially after 9/11, the same measures starting to be put in place in the US and Europe, I began to think a lot about those differences, and how they came to be. I started to take photos of what I observed, but I came across the problem that I looked very suspicious taking pictures of security. More often than not you are not allowed to take pictures of security, for security reasons. They can observe and document you, but not the other way around. So I started to make drawings and paintings, but then I found clever ways to photograph more discreetly and started photographing more seriously again.

AH: What is the political impetus behind your work?

RA: I don’t have a political agenda, except maybe to try to de-polarize arguments in favor of understanding their complexity. I feel strongly that art should not operate as propaganda because then its sole purpose is only to illustrate ideas and not to examine them. Instead, I hope to start a dialogue about aspects of society and politics that are unfortunately usually expressed with reductive arguments.

Artist Info

Writer Info

Alison Hugill has a Master’s in Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on marxist-feminist politics and aesthetic theories of community, communication and communism. Alison is an editor, writer and curator based in Berlin and a host of Berlin Community Radio show ‘Hystereo’.