Article by Alice Bardos // May 24, 2016

Clemens Behr is a Berlin-based street installation artist originally from the small historical west German city of Koblenz. His works are heavily influenced by three aesthetic streams: architecture, street art and graphic design. The artist’s simultaenously constructive and destructive sculptures have been planted in interior and exterior environments internationally. They draw off of the local geometry of cities like New York, Saint Petersburg and Marrakech, as well as the energy and orientations of the inhabiting people.

Heavily inspired by dadaism, Clemens Behr’s works challenge the impressions that the buildings, from which his installations grow, leave on the general public. To the artist, it is the reception of his work that acts as a mirror of the audience’s specific sociocultural identity. However, a common visual thread in his art is the look of having been caught by an organic disease or virus which has manipulated the fundamental scale and identity of the surrounding buildings and is now giving rise to an uncanny mimicked form.

Clemens Behr: ‘Rauminstrallation Lillienstraße’, Installation // Courtesy of the Artist

Alice Bardos: What parts of Berlin’s cultural scenes influence your work?

Clemens Behr: Generally, I don’t really like Berlin’s dominant music scene. If you don’t care where you go you will find the same shit everywhere. But, if you dig a little deeper than you can find really nice stuff, of course. There is a little scene for everything in every town.

In terms of music, I have a hip hop background. But I don’t really go to a lot of hip hop parties, because they are the same as they were twenty years ago. So I mostly enjoy electronic experimental music I think. I also really enjoy sound pieces that you can find in galleries and museums.

As for public art, I don’t really think that there’s a lot happening here. Mostly, there is a lot of graffiti which I really like, but I think the scene in Berlin is kind of split up into graffiti or fine art.

Clemens Behr: ‘Samples and Variations’, Installation, 2014 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: Berlin is city who’s surfaces are heavily coated with graffiti, what are you impressions of this art form?

CB: It’s one of the nicest features of Berlin. It makes the city so alive. Though the whole city has a lot of graffiti, most of the artists hang out in Kreuzberg, Mitte and Neukölln, so that’s where a lot of new works are made constantly. You don’t find so much at the airport [laughs].

Everyone accepts it, even the older generations. They know how to deal with it unlike in small towns. Still you see graffiti erased on the fancy new buildings, but I think in a couple of years that will change as well.

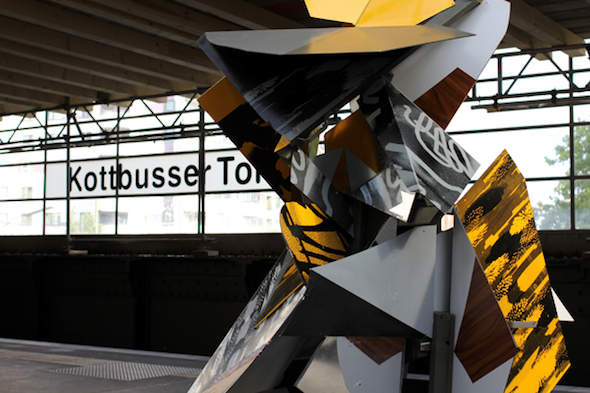

Clemens Behr: ‘Kottbusser Tor’ // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: In your art there seem to be three main elements: architecture, graphic design and street art. So why do you choose to bring them together in you art? What themes do you try to explore through them?

CB: The way I grew up was by using parts of the cityscape in a different way. Since I used to skateboard and do graffiti, I had an eye that developed to look for ways of using parts of architecture in a different way. I was always looking for obstacles to skate over or a wall to paint. An obstacle for skating has really three dimensional elements, it’s a space or non-space. Painting has a graphic element. This all combined, for me, just made sense.

Clemens Behr: ‘Suspended Bins & Broken Windows’, Lillestrøm, 2012 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: Can you talk a little bit about the choice of location for your installations, for example the types of buildings or spaces that attract you the most?

CB: In the past I always used to look for my own spaces, but then there was the complication of whether it was possible for me to work there: for example, if it was a super busy street. I would document the location first, and had to consider if the architecture worked in terms of colour, material and shape. Then I had to consider how I would mimic or merge these elements in my works.

In Berlin, I was annoyed by the street art bubble, so I’m not motivated to work in the public here on my own because here, of course, everyone is an expert. Here everyone knows everything. Everybody reads all the blogs, and I’d rather choose locations where people are surprised. If I work on my own without a commission I’d rather work in some small town or village where nobody ever saw work like mine before, there it would really have an impact.

Here, if I made an installation on Oranienstraße, everybody would be like: “Wow, look! It’s this and that by so and so!”. I’m kind of annoyed. I would much prefer working abroad I think.

Clemens Behr: ‘Suspended Bins & Broken Windows’, Lillestrøm, 2012 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: Tell me about one of your favourite installations that you’ve created.

CB: One of my favourite pieces is in Lillestrøm, Norway. I really like it because it was the first time I really got the construction and deconstruction of the space right, and the whole concept really worked out, so now I use it as a good reference, even though it’s not really large. The space itself was a white cube. It didn’t even have windows. I just had loads of material and really good circumstances to work with. I just had a carte blanche to destroy the whole place [laughs].

Clemens Behr: ‘Rojo Barcelona’, Installation, 2010 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: Cities seem to always be in motion through the people, interactive elements and machines, do any of your works reflect that?

CB: Last week in Saint Petersburg I created a social maze. If you are standing in the installation there are many doors: if you open yours, you close the door for someone else. I really like the idea of things folding and unfolding, which is also very pragmatic for smaller works. Kind of like how origami works, first being flat and then being folded and unfolded to have a volume.

Clemens Behr: ‘Rojo Barcelona’, Installation, 2010 // Courtesy of the Artist

This installation in Russia was a political exhibition. It was about the refugee crisis. I’m really not political with my work otherwise, I try to usually stay as abstract or quiet as possible when it comes to politics, but in this case it made sense for me. The point was very simple and clear, if you are together in a house you can imagine what the opening and closing of doors means.

Clemens Behr: ‘Morocco’, Installation, 2011 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: What is the process of getting inspiration for each city that you work in?

CB: One of my first good experiences abroad was in Barcelona: it was really warm so everyone was living outside, it had a really outgoing vibe, but I also felt really anonymous there because I didn’t speak Spanish. I didn’t really know what people were saying, so I just did what I wanted. I didn’t feel judged at all. It was the first experience I had abroad where I felt a difference from life in Germany.

Then, the experience was different in Marrakech, there were motorbikes and donkeys and I could really feel that the people were approaching the works as something that they’d never really seen. It would be very unusual to see a cardboard installation there. The work merged into the architecture there so the people could still understand it. Maybe they didn’t get the entire idea, but they didn’t really seem to care.

Clemens Behr: ‘Morocco’, Installation, 2011 // Courtesy of the Artist

A month later I was in New York and everyone was taking photos and blogging about my work there. Maybe selfies weren’t so big in 2011, but they took photos in front of the work. Those are the two big contrasts: everything else is in the middle. It’s always about how this high art culture has developed among the general audience. Of course this is about the perception people have of my work, but it is also about my perception because I work in the public.

It also has me thinking about if Berlin is the right place for me. There are a lot of new people coming here and Berlin is turning into a metropolis, it’s making the city more alive with new stuff. Now there is a little bit of everything from all around the world. Of course, the Berlin winter is still very cold, and there isn’t a beach here, or any fresh fruit, so it’s still like a northern German city. I’m not sure, but when I can afford it, I will get a house in Portugal, or something like that [laughs].

Clemens Behr: ‘New York’, Installation, 2011 // Courtesy of the Artist

Clemens Behr: ‘Blue Wall Closes Mall’ // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: What is your opinion about these changes happening in Berlin?

CB: Some people talk about the changes happening as bad because of gentrification. Growth is the destiny of Berlin, it’s the capital. It’s strange that it didn’t happen before. I feel the pressure too, I have to move my studio now because it’s too expensive.

Personally, I’m really curious what Berlin will make out of it because there is still a lot of resistance. If people come together they can really change something, it seems to be working. It’s not like in London where there is so much money involved that the government says “we’re going to do this” and nobody can change it. I don’t feel involved in the developments, but I’m curious.