Swaying robotic arms and bending frequencies are features in the playground of Joris Strijbos. His goal in tinkering with the potential of each digital and mechanical element is to produce a generative system—to make a thing which can in turn create novel results. This is the exhilarating edge that being a generative artist offers, playfully pushing the boundaries of common perceptions of what machines and organic and conscious beings are. If an object can create something unexpected, does that make it essentially more a part of nature?

These are the themes at the centre of the Dutch artist’s research, including his two pieces ‘Axon’ and ‘Homeostase’, in his current exhibition ‘Oscillations’. When I spoke with Joris Strijbos, his fascination with mimicking biological behaviour seemed to have wider and further reaching implications, extending beyond the scope of art, and grasping at the potential for self-sustaining isolated life in tandem with mechanical art.

Joris Strijbos: Axon, Steel, electric motors, electronics, LED lights, variable sizes, 2016 // Courtesy of the Artist

Alice Bardos: Tell me a bit about your background. How did you become an artist working with kinetic audiovisual installations and new media performances?

Joris Strijbos: I started out as an electronic musician so I went to an interdisciplinary faculty between the arts academy and the conservatory. Combining these factors led me towards kinetic sound and light installations.

I still make electronic music, and I design the sound for my installations.

I mostly program synthesizers that make the sounds. For ‘Axon’, I programmed a kind of synthesis in the computer with many variables that are linked to motion and light. The sound can interact with other variables in the installation like the light sensor. This procedure is generative and in realtime. There are feedback loops between various media, the sensors, lights and sounds. It’s based on an algorithm that will keep the responses evolving overtime.

AB: What do you experience when you listen to the sound component of your installations?

JS: For me, it’s purely abstract. What I like in the sound, is that it has a similar quality to sounds you could find in nature: for instance, the wind in the trees. It has the many layers that are constantly playing around and it get’s to this meditative state.

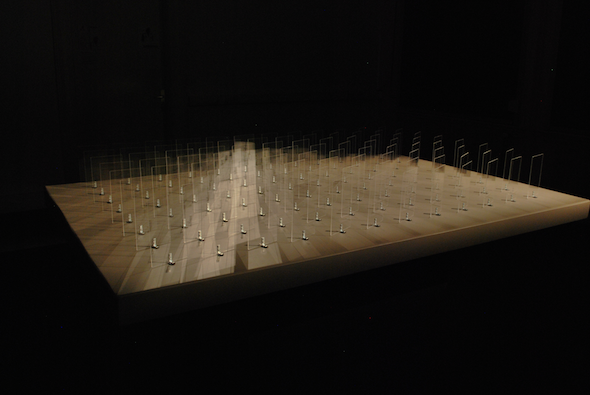

Joris Strijbos: ‘Phase=Order’, 2010 // Photo by Eric Parren, Courtesy of the Artist

AB: How did you learn to do all these technical things like program the algorithms for your installations?

JS: It wasn’t particularly at school. In my department there were a lot of people working with similar technology, but they mostly created the environment where I could choose what technology I wanted to work with and then I just learned it on my own.

AB: Let’s talk about the ‘Oscillations’ exhibition. How is it related to your previous work?

JS: These two works are part of a larger series of works that deal with trying to create a cybernetic or feedback system that results in emerging behaviour. So it mainly uses hardware, electronic lights, sounds and sensors. These are all connected in ways to create an unpredictable outcome. The core of that is in looking at nature, and being amazed by how some biological phenomena work and trying to find some underlying rules in that, then program them in artificial systems.

Joris Strijbos: ‘Homeostase’, Steel, electric motors, electronics, halogen lights, variable sizes, 2016 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: You said nature is a large part of your inspiration. What in particular fascinates you?

JS: It’s not about a single memory. Maybe it’s more about the general idea related to how cities are formed. It’s all about this emerging behaviour. For example, where you would see that things are being formed over a longer period of time.

Before, I worked with the patterns you would see in the flocking behaviour of birds. These flocks that constantly move around and follow each other with fluctuating movements, that’s what I really like.

AB: Is that connection between natural and artificial systems political for you?

JS: No, it’s more just fascinating that it’s possible.

AB: Is there anyone who has inspired you, any scientists or artists?

JS: I would say Ken Rinaldo’s ‘Autopoiesis’ piece. It kind of deals with the same principles.

A lot of inspiration comes more from different disciplines, like the visual music scene. For instance, Thomas Wilfred made ‘Lumia’, which has these wheels and mirrors. It’s a rotating mechanism that he projects light on and it’s scattered on a projection screen. It involves ever-changing, evolving abstract light patterns. That connects to what I try to do. It concerns the idea that you kind of look at these works like musical works, so it’s abstract.

Joris Strijbos: ‘Homeostase’ for the Glow Festival, 2012 // Courtesy of the Artist

AB: We’re living in a time when technology is developing rapidly. Is there anything that excites you about the possibilities in the future?

JS: Actually I’m not so focused on new technologies. I don’t use the newest forms. All of these works could have been made in the sixties or maybe earlier. When the first wave of cybernetics began to develop.

AB: You’ve done a lot of collaborative projects. Can you tell me about one that you’ve really enjoyed?

JS: I’m a part of the Macular Collective. I’m working with a few people there. Recently, I’ve been collaborating with Nicky Assmann, we did a series called ‘Moiré Studies’. We work with grids and rotating lights, the shadows cast on the white wall interfering with the grid itself. It’s a very experimental process, with two people it works really well.

Joris Strijbos: IsoScope for Dark Ecology, 2015 // Photo by Jeroen Molenaar, Courtesy of the Artist

AB: Do you have any ideas about what you want to work on in the future?

JS: We’re working on a project that’s connecting kinetic sculptures, new media and alternative energy sources. It will work as a sort of land art project, having the installations outside running on wind or solar power.

The idea partly started when I was invited by the Dark Ecology project in Norway and Russia. They asked me to come on a journey with them and then propose a piece inspired by it. We were on these rocks, and in the area there was the Aurora Borealis, which inspired me. I was meant to make a manmade phenomenon while working with wind energy and connecting it back to my earlier research into cybernetics. The result was a work called ‘IsoScope’.

From that project I was inspired to create a lab where a lot of people could work on similar projects. We recently went to Joshua Tree in the United States with some individuals from the Macular Collective and began exploring the potential of solar power there.

For me the sustainability component is important because it means that there could be this robotic community out there on the mountain harnessing energy for itself, in theory. If you build it properly, it could be there for ages. It becomes more like an artificial living system.

Exhibition

NOME PROJECT

Joris Strijbos: Oscillations

Jun. 25–Jul. 30, 2016

Dolziger Straße 31, 10247 Berlin, click here for map