In a performance, the effect of light has the potential to enormously transform the perception of a mo(ve)ment. Light, as a language in itself, not only narrates but also veils various situations. In that sense, how does the professional audience—like the theater director—approach lighting?

Annemie Vanackere has been curating dance and theater since the 1990s. After acting as co-director of the Rotterdamse Schouwburg, Vanackere moved to Berlin in 2012 to become the director of Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) Berlin. At HAU, together with her artistic team, she is curating and presenting a diverse programme of contemporary performing arts as well as robust festival programming, such as the recent ‘The Aesthetics of Resistance. Peter Weiss 100.’ Besides the pieces that had an impact on her in terms of light, Vanackere talked about how HAU reflects upon the changes in society and her opinions on the latest debates in the dance-theater scene of Berlin, in light of the recent Volksbühne controversy.

Portrait of Annemie Vanackere // Courtesy of Hebbel am Ufer, © Dorothea Tuch

Göksu Kunak: Besides the concept, how do other elements of a piece, like lighting, affect your perception? Could you give some examples of those pieces in which you were focussed more on the light than dramaturgy or concept?

Annemie Vanackere: We work in a very visual art form. There is also theater that happens in darkness, but usually it’s really about watching and listening: besides some pieces with touch, smell or taste, but those senses are still underrepresented. So, lighting is one of the main actors of a piece. In the works of Swedish choreographer Jefta van Dinther, for instance, choreography, music and lights are three autonomous actors, which means that the lights not only support or illustrate the work, but are also a crucial part of the work. His piece ‘Grind’ is unthinkable without the collaboration with the light designer Minna Tiikkainen. That’s not always the case: it probably happens more in dance than theater. From time to time, in relation to the corporeality of the dance performance, the light becomes almost tactile. For instance, the way Jan Maertens works with Ian Kaler, or with Meg Stuart in ‘Violet’. The light is a very strong transferring element in Maertens’ work. For these quite outstanding light designers, light is a very vigorous performer in a piece. You see that there is a co-creation between the light designer and the choreographer, a congenial togetherness. In theater, a good example is Torsten König, the light designer at the Volksbühne, who often works together with Herbert Fritsch. Here, also, he is part of the rehearsal process and designs from that point. The light becomes a ‘performer’ in, or sometimes against, the piece. It’s not only: “I shout so there is red light.” Light is one of the meaning carriers. It’s another language that is more physical, and we want to understand, or rather sense, what it might be saying.

Jérôme Bel’s piece ‘Jérôme Bel’, which is 20 years old, is lit only with one light bulb. Light is a strong choreographic element in this piece, which is a powerful comment on the use of theatrical means. Instead of 150 projectors, all that’s needed is the one small element: the light bulb! Recently we’ve presented this work again and I ‘rediscovered’ this different approach to light as a part of the écriture, the scripture of the piece.

The infrastructure of the space is so affective. Somebody like Meg Stuart is very sensitive to space. Not only space and time, but also space and light are very much linked together. The dramaturgy of light: how the light is holding a piece, transforming it. I saw a piece of NEUER TANZ a long time ago at Tacheles in Berlin, probably in 1992. There was a light bulb on a long stick and the performer put the lamp in a bucket that was filled with black paint. Suddenly, the light was off. Because of the heat of the bulb, the paint started to melt down. So, gradually we started to see the haze and the light again. In the space of Tacheles, it was such a perfect scene. Besides industrial spaces or other non-theatrical spaces, a traditional theater space could also be a good container for these kinds of pieces. But, of course, you need clever light designers to deal with it.

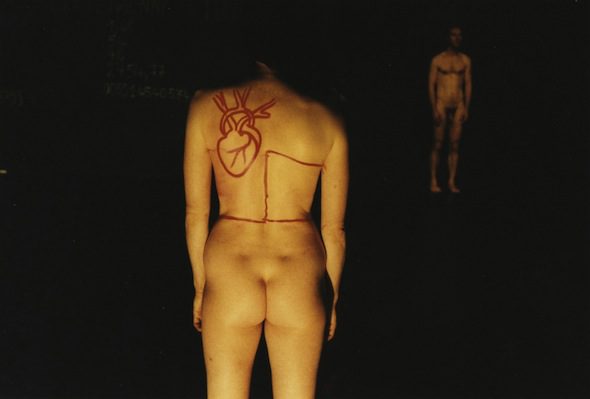

Jérôme Bel: ‘Jérôme Bel’, 1995, performed during Berlin Art Week // Photo by Hermann Sorgeloos, courtesy of HAU

GK: How are the changes in the city of Berlin in terms of gentrification or immigration reflected by the theater and dance scene? How do you think a theater like HAU could expose the problems of refugees and war without a Eurocentric approach?

AV: Firstly, I would like to stress that we do not ‘reflect’ issues but want to ‘reflect upon’ or about them. There’s a difference! We’re not just a mirror. HAU wants to offer an artistic reflection on various topics related to the city and the world. Our festival ‘The Aesthetics of Resistance’, which just opened the new season, asked the question of what resistance is, also historically, and where the spaces for are today, learning from Peter Weiss’ novel from 1974. In that sense, we’re also participating actively in a discourse of transformation: this is expressed by the guests we invite, by the artists, and by our critical and engaged audiences.

Without neglecting the positive aspects of the way Berlin is transforming—otherwise you and me would not be here—the singular history of the reunited city is getting more and more invisible. As things and even people are being polished away, crucial aspects of this history are still present in people’s minds and hearts. Therefore, sometimes we like to stop time and say: “let’s have a look at it and observe what has happened.” Concerning big geopolitical issues, we want to be specific, also in the context of theater, trying to figure out what we can learn from it for ourselves here and now. Artists bring us topics. There is a very strong exchange, almost magnetic attractions between them and the theater.

Sometimes people expect too much from art. At the same time, they don’t trust enough what art can do. Political problems will not be solved by the art world or the theater: political agency should be demanded. But artistic practice shows complexities—that things are not only how they appear to us—and it can show aspects of ourselves that we weren’t able to articulate before.

The issue of gender is always a strong subtopic in HAU. For instance, we talked about ‘City Lights – a continuous gathering’ as a feminist project with Meg Stuart and Maria F. Scaroni, but the title doesn’t shout this out. If people notice the fact that, in most situations, there is a male dominance and this time even the light designer (Sandra Blatterer) is also female, then it’s good enough for us, but if not, that’s also fine. We would like to show our positioning by doing things, rather than always directly pointing them out. Therefore, we don’t claim this as a feminist project. The audience will see an image and something might happen subliminally.

GK: Considering the debates about Volksbühne and the new director Chris Dercon, what is your approach to the changes in Berlin’s theater-performance scene?

AV: I always try not to judge too much beforehand. We don’t know yet what the change will look like. The only thing we can comment upon is the whole process, which was not well done in terms of communication. For the people who have been living in the city for a long time, especially in the Eastern part, Volksbühne represents something very particular. Also for me, when I was visiting Berlin as a theater professional, I went first to the Volksbühne, before any other theater house. I invited them to Rotterdam: I saw something that I’ve never encountered before, even though I did not understand German so well back then. I knew there were so many references that I couldn’t explain, but somehow it really affected me. I presented the three pillars of Volksbühne: Frank Castorf, René Pollesch and Christophe Marthaler. So, as a spectator and curator I have a connection to what this house represents. If you look at the German map, there aren’t many houses where the director would have such an impact. That’s why the whole debate becomes more difficult. I’m not against experiments, but is it really in this theater where an experiment should start? HAU was the first place in the city with a different artistic agenda. Also before it became HAU, the Hebbel-Theater had an international approach and was an actor for change and exchange. I feel very honored to be in that tradition.

Meg Stuart, Maria F. Scaroni: ‘City Lights – a continuous gathering #1-5’ // Photo by Alexa Vachon, courtesy of HAU