Article by Ursula Ströbele in Berlin // Tuesday, Apr. 25, 2017

Over the last few years, there’s been a renewed interest in fabrics as material for art. Berlin-based artist Anja Schwörer has been working with textiles for more than 15 years, exploring the limits of painting through her unusual approach to fabric. Bleaching, folding, stacking, unraveling, cutting, scratching and sewing belong to her personal “verb list” (Richard Serra) and describe the main characteristics of her artistic practice, through which she often receives unexpected outcomes. The nearly alchemical processes she employs relate to material, place and process yet her formal language remains abstract, often geometric and symmetrical.

Traditionally considered women’s work, and connected with handcraft, textile arts have been used throughout the history of art in diverse ways—by Richard Tuttle, Lucio Fontana or Blinky Palermo, for example—artists who have been an inspiring starting point for Schwörer’s own work, in addition to the unique handling of color and canvas by Agnes Martin, Kenneth Noland, Giorgio Griffa or Helen Frankenthaler.

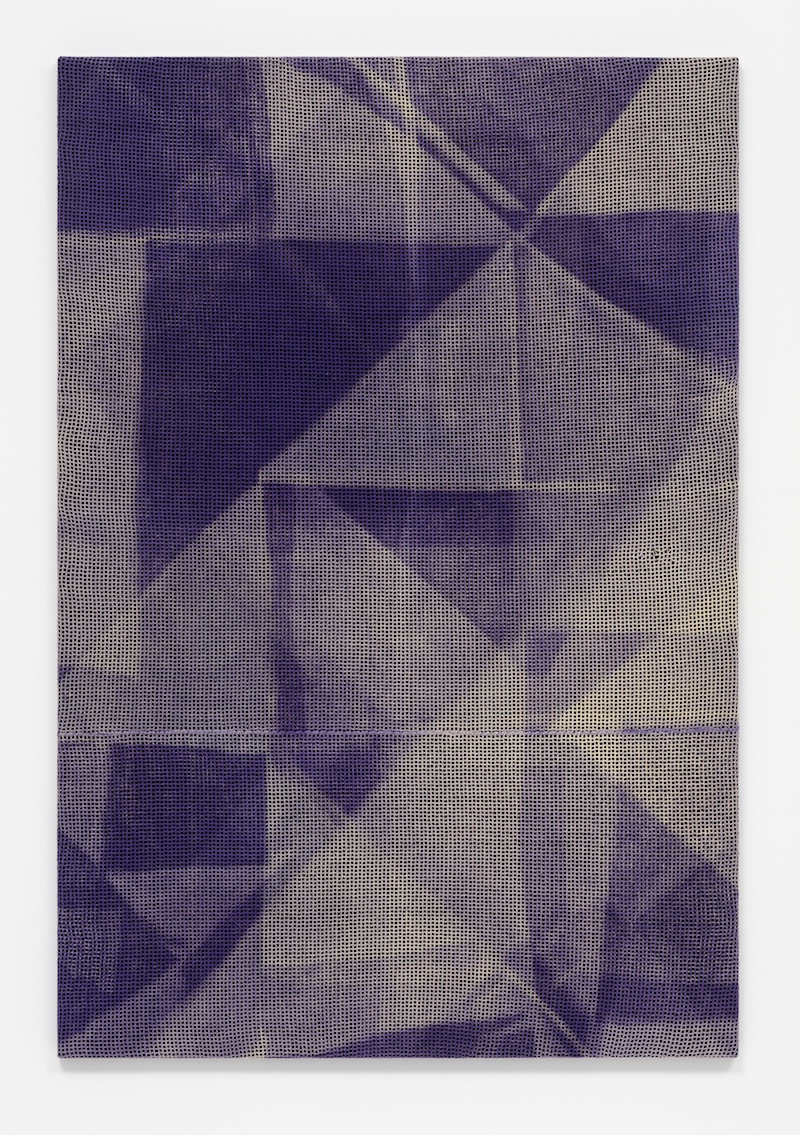

Anja Schwörer, ‘Untitled’, dye and bleach on mesh fabric // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

Ursula Ströbele: You have been working with textiles for many years, expanding the boundaries of painting. Contrary to more traditional ways of painting, where the color and the pigments are put on the canvas, your works are characterized by a different approach, which seem to be less additive, but rather where you take something off the (supporting) material. How do you describe this process and where does this interest come from?

Anja Schwörer: Yes, that’s right. In my practice the colors emerge out of a deletion in a way. I often work with factory-dyed textiles from which I take off the primary dye through various bleaching processes. The erasing of the original colors is an important aspect. I see this step rather as a sculptural act, as I scrape out forms and structures from the canvas. Furthermore, I fold, clamp and tie-up the fabric. Fabric bundles are lying in dye baths, they got washed-out, towel-dried, ironed, folded up and dyed over again. Only at the end of all these working steps, does the picture get stretched on the frame.

I have to admit, that for a long time I was inspired by tie-dye techniques and the tradition of batik. While at the Art Academy I started to do batik by myself.

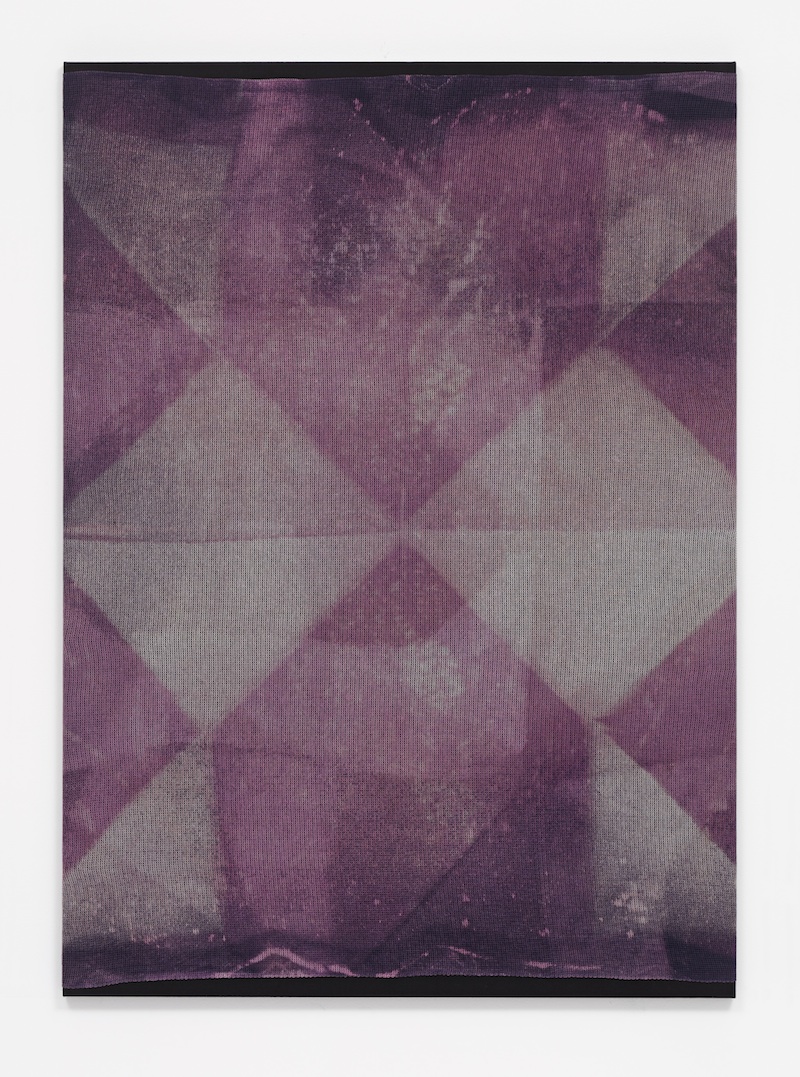

Anja Schwörer, “Untitled’, 2016, dye and bleach on mesh fabric // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

US: When you are traveling, you like going to markets where they sell all kind of cloths and textiles, such as in Istanbul or Jerusalem. Could you tell more about where you find the fabrics you use?

AS: Well, the most important feature and the fascination of textiles is their haptic quality, their structure, their materiality. You can feel this by touching and looking at the fabric. And, of course, when I am travelling I always visit the local fabric stores and the markets. Online shopping for fabrics was often a big failure. But, here in Berlin, I have found some really good fabric stores, too. I like to buy my fabric at Gebrüder Berger in Schöneberg. It is a family-run company with very nice people working there.

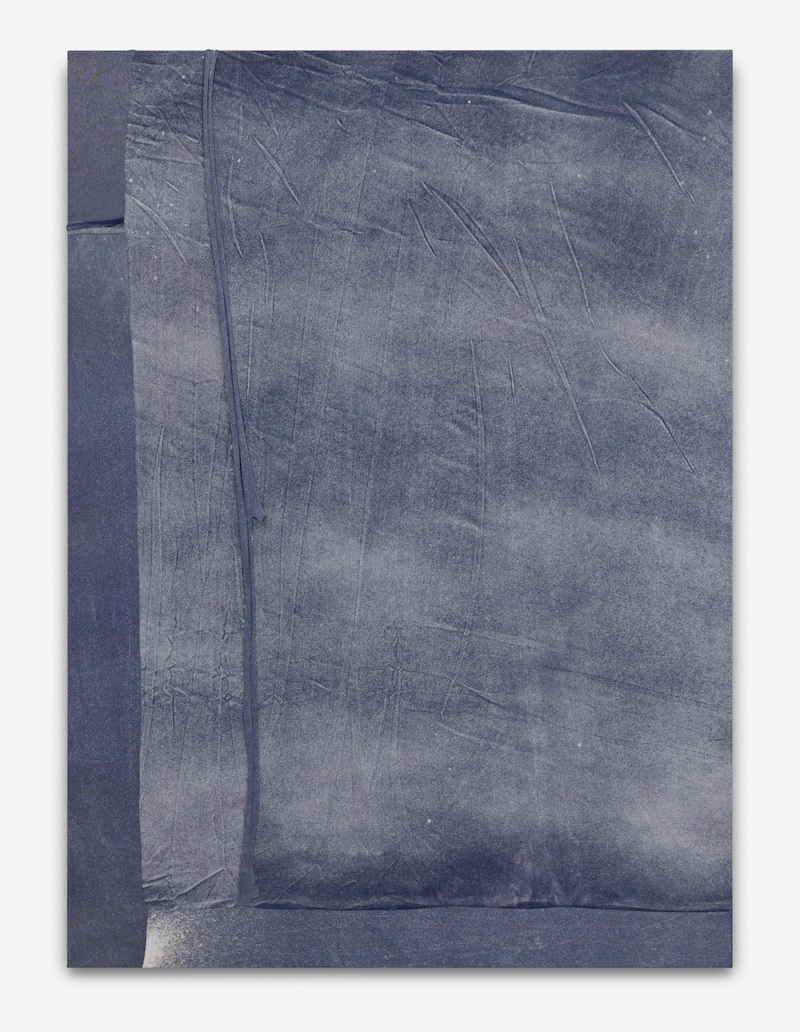

Anja Schwörer, ‘Untitled’, 2014, sewn fabric // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

US: There is a common saying: “Clothes make the man.” Is the background and the way fabrics are made important and inspiring to you?

AS: Particularly in my work with denim as a main material, I am very much interested in the cultural and the subcultural background of the fabric and its history.

How can a fabric, a piece of clothing (like jacket or pants) and outfit indicate a kind of youth movement and rebellion? And then, over time, become a mass-produced and extremely popular garment. It is striking that fashion-conscious people wear washed-out and worn-out trousers with a lot of holes and stains. Holes, scruffiness and folds—that are usually signs of a longterm individual relationship with your clothes—are instead artificially mass produced. The used-look is getting fashionable and a whole industry is creating this kind of aesthetics. I am also curious about the look of the faked aging process and the overdone bleached sections that develops an obvious ornamental impression on the cloth.

Anja Schwörer: ‘Untitled’, 2015, bleach on denim // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

US: What role do chance and unforeseen moments play in your experimental way of working? Is the paradigm “truth of material” relevant to you?

AS: Yes, chance plays a crucial part in my work, as I cannot control everything. Often, ideas and pictorial approaches start out from unexpected reactions and developments. The textiles I use are going through diverse working methods, which I cannot always navigate completely and I don’t always want to. It is an experiment with the fabric and its characteristics. I am interested in how the fiber is reacting to water, to sunlight or bleach. The chemical procedures and the mechanical treatments leave their marks and create the image. There’s nothing hidden here, but unfolded.

Anja Schwörer: ‘Untitled’, 2014, bleach on mesh fabric // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

US: In your latest series you started using a new kind of fabric, that is more permeable/diaphanous and that you fold multiple times, reversing the inside and outside.

AS: In my latest works I am using a mesh fabric that is very roughly woven with an obvious grid structure. The bold structure intensifies the materiality of the work and leads my work in a new direction, I think.

As often in my work, the fabric has been folded several times. While the canvas is folded I cover the fabric with a bleaching detergent. I repeat these folding and bleaching steps and rework the picture. This part of my working process is a kind of mark-making, where the current status of the folded fabric gets captured and recorded. In the painting, you can still see the former folding lines and outlined shapes. Some of them are blurring away, some are getting lighter and even sharper.

The bleaching process functions as an imprint, like an impression of the moment. This practice is related to printing techniques and to photography. Parts of the fabric are covered and parts are exposed to the bleach or sunlight, similar to a photographic process. It is about light and shadow and the effects of positive and negative imaging.

Anja Schwörer, ‘Untitled’, 2017, dye and bleach on mesh fabric // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

US: That’s interesting, it’s like leaving traces or even inscribing abstract hieroglyphs in the pre-existing textiles. You have always tried to expand the possibilities of painting within the framing conditions you set, stretching it to the edge. It seems that you are now focusing more on optical effects, some evoking painterly gestures, fuzziness, overlapping patterns, pixel-like structures, that direct the viewer’s perception.

AS: Yes. The folds create geometrical patterns, figurations emerge. The imprints on the fabric reveal spatial configurations on the picture plane. Sometimes the interferences create the so-called moiré effect, which occurs when two similar patterns are slightly rotated against each other. Mostly they appear as an artifact of digitally-produced images, but the interaction also happens when I get my work photographed. In that case, you get this visual error by reproducing it and by printing it. But in my paintings they refer directly to the structure of the fabric, because I am generating it by overlapping the material.

Anja Schwörer, ‘Untitled’, 2016, dye and bleach on mesh fabric // Photo by Hans-Georg Gaul

I like working with different sorts of mesh fabrics because the visual result is varying. Textiles that have a fine mesh structure, almost like a fine screen, create a different visual effect than honeycombed fabrics. Some fibers almost have a knitted character that you can see through and this causes an interaction with the layers underneath. Depending on the size of the mesh fabric, the canvas can also starts to flicker, when you stand at a certain distance from the painting. The dimensions of the mesh configurations cause a misty image, like an optical illusion.

Artist Info

This article is part of our BLINK series, which introduces the practices of artists around the world. To read more BLINK articles, click here.