The commercial corridor on Degnan Boulevard that intersects W. 43rd Place is commonly seen as the nucleus of business activity and cultural output in Leimert Park. A predominantly African American neighborhood in south Los Angeles’ Crenshaw District, Leimert Park is distinguished by its array of old Spanish colonial revival buildings and pine tree-lined streets. In the past, it was the site of Brockman Gallery, started by Dale and Alonzo Davis in 1967, seeing a lack of accessibility to the arts after LACMA moved from Exposition Park to the Fairfax/Miracle Mile District. The gallery helped spur years of happenings, concerts, and a heightened sense of community that can still be felt in Leimert Park today. Brockman closed in 1990, and the following years in the 2000s saw rising rents in the commercial shopping area that led to a dearth of retail and access to art galleries once again.

Opening reception ‘Spiral Play: Loving in the ’80s” at Art + Practice‘, Los Angeles // Photo by Natalie Hon

Artist Mark Bradford, however, is changing that. Along with his partner, activist Allan DiCastro and collector/philanthropist Eileen Harris Norton, Bradford envisioned and realized Art + Practice, a foundation whose mission and program spans that of a center for foster youth and contemporary art gallery, in 2015. The foundation also works directly in conjunction with UCLA’s Hammer Museum. Founding the gallery and partnering with the RightWay Foundation for foster youth (Los Angeles County has the largest population of foster youth in the United States, with South LA having some of the highest percentages), Bradford has followed in the Davis Brothers’ footsteps by acknowledging a gap in the local community and aiming to serve its residents.

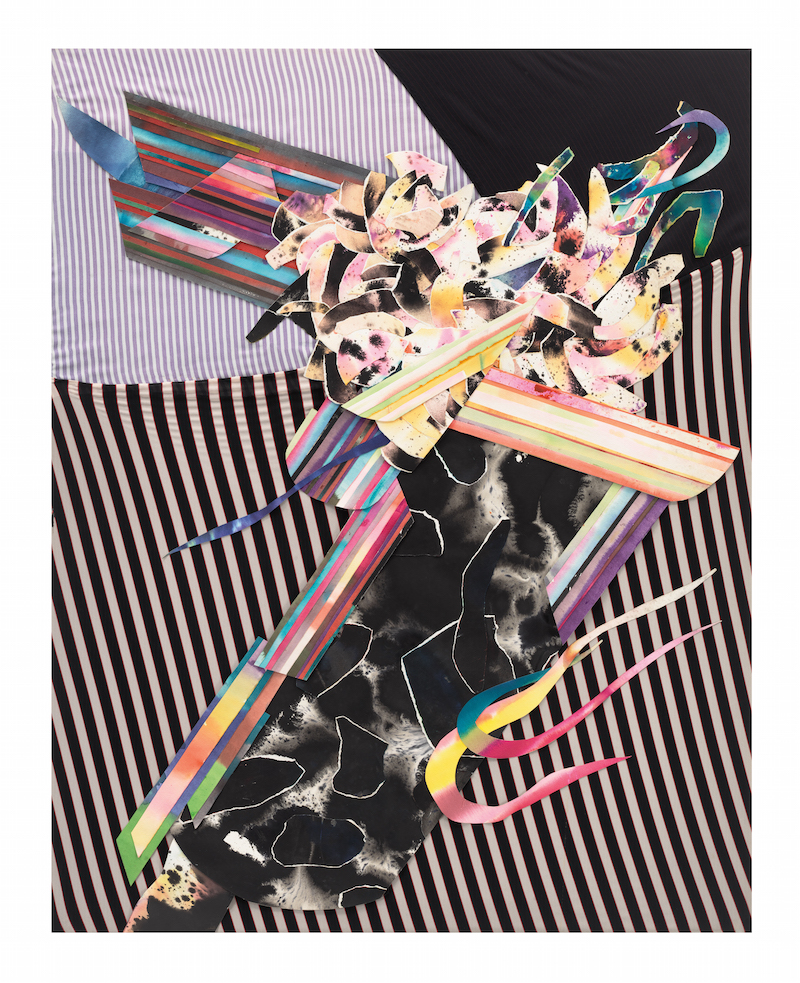

Al Loving: ‘Mercer Street VII, #9’, 1988, paper collage, 43 1/4 x 28 inches // Courtesy of the Estate of Al Loving and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

The current show at Art + Practice, ‘Spiral Play: Loving in the ’80s’, presents visitors with the groundbreaking work of Alvin D. Loving (1935-2005). Curated along with the Baltimore Museum of Art by Dorothy Wagner Wallis, Christopher Bedford and Katy Siegel, ‘Spiral Play’ showcases Loving’s dynamic career in the 1980s, where his work included not only painting but also found materials, cardboard, and various media. Perhaps the most radical manifestation of his career in this decade would be his heavy employment of spirals—a symbol Loving learned was essential in Afro-Caribbean religious traditions, like Santeria, while on a trip to Cuba.

But before his relationship to the spiral flourished, Loving’s work was dominated by the cube. Originally from Detroit, Loving moved to New York City in 1968 after receiving an MFA from the University of Michigan, where he subsequently had his first solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. His reputation and oeuvre expanded as a result of his meticulous and rigid paintings of cubes and other geometric shapes, taking inspiration by German artist Hans Hofmann.

Al Loving: ‘Untitled’, 1982, mixed media, 60 1/4 x 48 inches // Courtesy of the Estate of Al Loving and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Loving’s paintings of cubes are in many ways contradictions; the dedication to straight and angular modules renders the images flat and inanimate: microscopic assemblages of inorganic and crystalline matter. Yet, simultaneously, the splashes of color and near-perfection in mastering the shading of these various cubes, prisms and cells creates the illusion of three-dimensional objects that emerge from the canvas and engage the viewer. But the cube, which had brought Loving much success early in his career, also trapped Loving within its confines, and he sought to discover other forms and media to incorporate into his art.

In ‘Humbird’ (1989), Loving creates a massive collage that uses newspaper articles, cardboard and paint. Contrasting from his cubic paintings that were often matte, ‘Humbird’ is glossy, covered in a thick shellac and filled with spirals of all shapes and sizes. While hanging, it protrudes slightly off the wall, further facilitating an optical effect as if popping out from the surface.

Al Loving: ‘Humbird’, 1989, mixed media on board, 72 x 100 inches // Courtesy of the Estate of Al Loving and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Amid Loving’s new-found interest in the symbolism of the spiral and its associations with continuity and growth, works like ‘Barbara in Spiral Heaven’ (1989) also demonstrate Loving’s commitment to revisiting and acknowledging his previous successes and associations with the cube. ‘Barbara in Spiral Heaven’ is a piece dominated and laced by spirals, but espousing one very conspicuous cube on the right side, celebrating the artist’s evolution. It is in these works where Loving is free. Loving’s work in the late ’60s, dominated by the cube and other geometric shapes, were literally and figuratively limiting, closed off. With Loving’s appropriation of the spiral, he discovered a motif that espoused infinite possibility and progression.

‘Mercer Street VII, #9’ (1988) once again employs Loving’s cube. However, like the cube in ‘Barbara in Spiral Heaven’, it is less reinforced, almost weak, and not even three-dimensional. These imperfect boxes, in this case, are abstracted so as to create windows in a building or house. The fact that this collage is constructed of dyed and torn paper adds to the feeling of delicacy. Meanwhile, pieces like ‘Untitled’ (1982), abstain from using any cubes or spirals, and instead incorporate fabrics and other media to create robust pieces, reminiscent of Rauschenberg’s combine paintings.

Exhibition Info

ART + PRACTICE

Al Loving: ‘Spiral Play: Loving in the ‘80s’

Exhibition: Apr. 22 — Jul. 29, 2017

3401 W 43rd Pl, Los Angeles, CA 90008, click here for map