Interview by Alison Hugill // Aug. 30, 2019

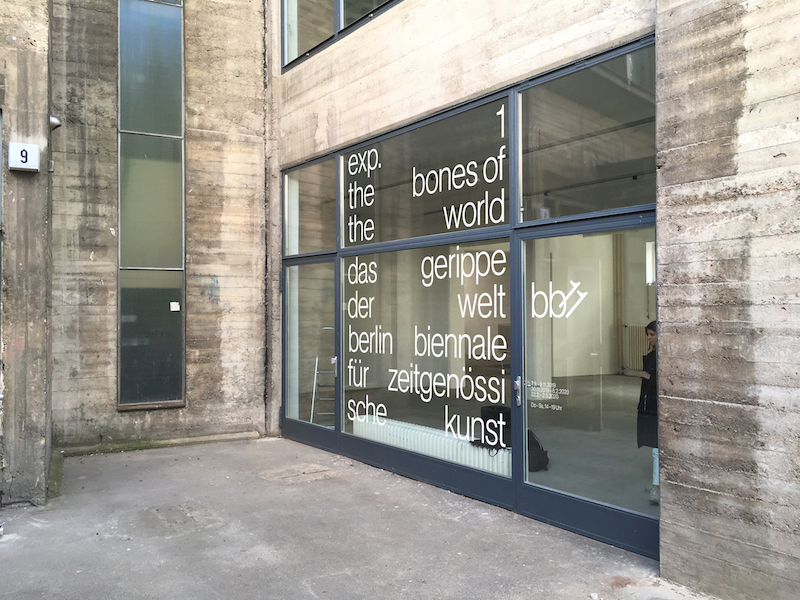

On Friday, September 6th, the curators of the 2020 Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art will open the doors of its temporary venue, the ExRotaprint architectural complex, in Wedding. With ‘exp. 1: The Bones of the World,’ the Biennale will stage a “housewarming,” inviting visitors to explore over 25 contributions in diverse formats. The curators explain the concept of the “housewarming” as “an exercise in mutual exposure, a place to listen to the stories that shape us.”

This Berlin Biennale is uniquely process-based, focusing on lived experiences and seeking to build sustainable relationships with the people and city of Berlin. The title of the first experience, ‘Os Ossos do Mundo’ [The Bones of the World], comes from a travelogue written by Brazilian artist Flávio de Carvalho (1899–1973) during his time in Europe in the mid-1930s. According to the curators, “it is a joyous acknowledgement of life occurring amidst, against and despite the general states of brokenness all around us.”

Curators of the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, f. l. t. r.: Renata Cervetto, Agustín Pérez Rubio, María Berríos, Lisette Lagnado // Photo by F. Anthea Schaap

Ahead of this inaugural event, we spoke to María Berríos and Lisette Lagnado, two members of the four-person curatorial team, also consisting of Renata Cervetto and Agustín Pérez Rubio. Berríos and Lagnado both have backgrounds in sociology, and have worked together in the past on an exhibition at Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, which looked at alternative architectural models in Brazil and Chile from the mid-twentieth century. We discussed their visions for the 11th Berlin Biennale.

Alison Hugill: Can you tell us about the nature of your collaboration, as a four-person curatorial team? What is your curatorial process like, coming together in this new city and context?

Lisette Lagnado: This is a point that we haven’t addressed yet: it is not only about joining forces and working together but about sharing experiences and responsibilities. When I accepted to make this biennial after São Paulo, it was clear to me that I didn’t want to reassert the format of one principal curator with associated curators. For me, it was important to share this task with people for whom I have a lot of respect, and we managed to compose a heterogeneous group with complementary skills. We need to be able to share the good and the bad of this one year and a half working together.

When Agustín and I were approached, what was clear to me was his passion for contemporary art and his commitment to queer studies around the world, which has also been a focus of my research in Brazil, where I’m usually based. In this sense, it was important for us to join forces.

María Berríos: To complement a bit what Lisette has said, coming together in a different city means something different for each of us. I have been moving around my whole life; I have a migrant background. I don’t really feel this sense of home that other people may have. I always have that sense of strangeness or duality. So to have to move here is more of a logistics problem for me because I have a kid, rather than an overwhelming challenge as a foreigner. I’ve always been a foreigner. That dilemma is a part of my life, as it is for many others.

But I do feel like I’m from somewhere: I’m from Chile, I’m from South America. My entire work has been about trying to figure out what that actually means. We have in common this attempt to construct this “South” that we are all coming from. Lisette and I have worked together before, and that was a very engaging experience. I really respect her work, which thanks to this previous collaboration I knew first-hand.

Materials for the visual identity of the 11th Berlin Biennale // Photo by Till Gathmann

AH: In your introductory press release, you’re described as an “intergenerational, female identified team of South-American curators”. How does Agustín fit into this paradigm of “female-identified” curators, given that he uses male pronouns?

MB: There are many ways of looking at that. It’s not a body identification. We are not trying to trick anyone into thinking that Agustín is a woman, which he clearly is not. We do think that it’s important that we are a majority women, in a time when we feel that the toxic masculinity that has taken over is really overwhelming. That statement was made the day that Bolsonaro was elected. It’s a contemporary moment where it’s just not possible for this to continue anymore. It’s not possible to have men ruling in this way; not men only, but these macho voices that take up all the space and really produce harm in the world. This squashing over-confidence, which is monolithic and articulated in a specific way, really needs to be questioned. We all come from countries run by these kinds of men: in Chile, in Argentina and Brazil. It’s really scary. It’s not a moment that we can be silent about this.

So it’s not about Agustín’s sexuality or his body, but about who we stand with and what our position is. He has been very committed to feminist and queer theory: amongst us he has the most stamps in this regard on his CV. Then again, for the rest of us, being a woman is just part of our everyday life. We also all grew up using a language, Spanish, which has been overtaken by male pronouns. We think it’s ok for him to be taken over by our pronouns for the duration of the biennale.

AH: You have both worked closely with architecture collectives and public space initiatives. This seems to have informed your curatorial outlook to some extent, especially in your choice of venue, as ExRotaprint has a community-oriented objective. What role does community participation and collaboration play in your practices?

LL: My background is not in art history but sociology and philosophy. Architecture was, for me, a way of having more public engagement with the impact of urban transformations on families and communities. When I worked with María for the exhibition ‘Drifts and Derivations. Experiences, Journeys, and Morphologies’ at Reina Sofia, I felt I was living in a moment where artists were going too deep into the market producing objects for international fairs. Flávio de Carvalho was also a key figure in that exhibition because he was an architect and, as a cultural agent, he acted in different fields and disciplines.

María brought in the poets from the Valparaiso School. For us it was important to understand how an agent or an artist can actually transform reality. To go through words and space, into real space (“l’espace réel”). Architecture collectives were a way to work with the possibility of going to the streets and experiencing another form of performativity.

MB: In my own trajectory as a sociologist, my research has always been interested in and engaged with collective practice. The arts seem to be a place that is still obsessed with names and last names—to the extent of even creating them when they don’t exist, to make sure the factory keeps working in that way. Even the most conservative historians don’t do what art historians do, continuing this linear, straight line of guys connecting all the dots. This idea of history is completely obsolete in every other realm of knowledge. What happens to collective practices and more anonymous practices within this logic? Why are their aesthetics just annulled within that discourse? My own practice has always been very collaborative. It’s never easy but always more enriching.

There is a strong tradition of collective architecture in Latin America from the 1960s until today. Architects were learning from the informal architecture of, for example, the shanty towns around Lima. There was an acknowledgement that architecture comes from these kinds of vernacular, self-building practices all over the world. Art is the same: artists are taking from the world and not the other way around. The relevance of collective practice is not just about being together, but about acknowledging that you are never truly working alone.

View ExRotaprint, mock-up for the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art c/o ExRotaprint Berlin, 2019 // Photo: Till Gathmann

AH: Why did you choose the ExRotaprint space as your residence this autumn and how will you integrate it, as well as the neighbourhood of Wedding, into the overall Biennale concept?

LL: It’s connected to the history of the Berlin Biennale. KW Institute is the main venue and sometimes the curators work in the vicinity, depending on the project. For ours, we see ourselves as foreign people inserted into the city, so an immigrant neighborhood fits perfectly. In this edition of the Biennial, the project starts with our experiences, and therefore we wanted a place to test ideas and thinking; a laboratory. The ExRotaprint venue was an idea that came from the Biennale team, as an interpretation of our proposal. We were super happy because it has a lot to do with creating long-standing, sustainable relationships, and this is an important point as a declaration of respect for those who are living here..

MB: It’s important to note that all biennials are linked to gentrifying the city with this kind of pop-in / pop-up culture, which many cities are super exhausted by. There needs to be an awareness of what that means. It is impossible to do now, what you could do ten years ago with a biennial. It’s also not acceptable, in many ways. You can’t just go and make crazy constructions inside semi-abandoned buildings.

We go into ExRotaprint with a lot of respect and care for what is happening around us and how they have managed to create this space within this perpetually unfinished building. It was declared a heritage space, and this cultural branding was used as a way to stop the gentrification madness and real estate speculation. They created a sustainable model for themselves that is very long-term. Within this context, we are very aware that our time is short, and we are there to learn from the context. We are in a setting where doing something is actually meaningful.

We care about having sustainable relationships with those who we come in contact with, and with artists who are actually based here. We are trying to inter-contaminate; bring people together. We are putting in the effort to just be there. It’s an act of mutual exposure. It was important to find this space to do that in a way that was careful and caring.

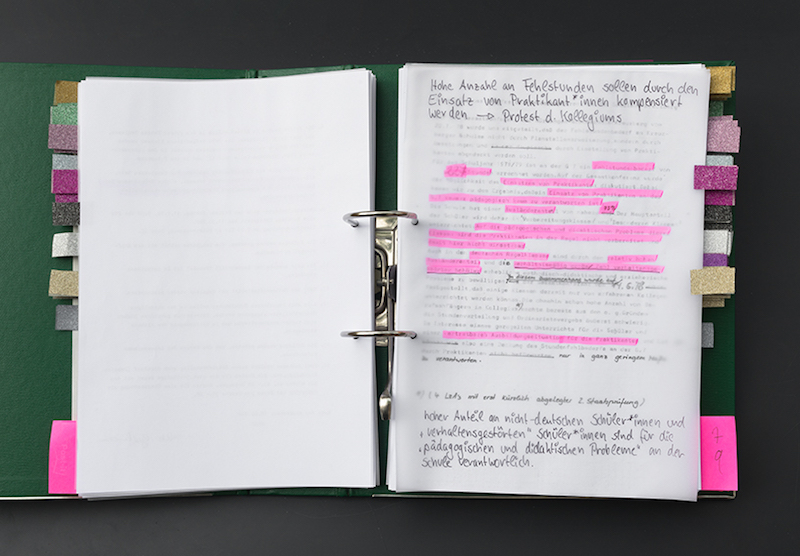

Miriam Schickler, Ayşe Güleç, Carmen Mörsch, ‘Das Archiv schweigt (oder doch nicht)?,’ (detail), 2019 from ‘Die Remise,’ installation view (detail), Nürtingen Grundschule, Berlin, 2019 // Photo by Maja Wirkus

AH: With your upcoming “Housewarming” for the Biennale residency space in Berlin, you’ll open the exhibition ‘exp. 1: The Bones of the World’ as a mise-en-scene for encounters with the public, the future audience of your 2020 presentation. What awaits us there?

MB: It’s not easy to use a biennial structure to do something that is more process-based, and not just the spectacle of process. This has been quite a challenge for us. It’s just not meant to be used in that way. Our idea for the space is to let people into what we’ve been thinking about. What you’ll find in the space is a kind of scene. It’s called an exhibition for communication purposes, but it’s more just things that are coming out of our own “homes,” in this mobile understanding of the word home.

LL: We struggled a lot to give it a category or name. We don’t speak German, and this poses a lot of difficulties. For us, in the Spanish or Portuguese language, it’s an “experiencia.” In German, it’s “Erfahrung.” It seems that in German “Erfahrung 1” does not work as a title. Experiment, a scientific term, would also be difficult because of the German past. We were trapped in linguistics here. And, for us, scene-setting is not an installation. It’s more mobile.

We have thought a lot about this and continue discussing the many translations. And, as María said, we are bringing our home, literally. Also our traumas. When we mentioned the female voice: Marielle [Franco], for example, the councillor of Rio who was assassinated, will be present. This is my baggage that I’ve come with and this is an opportunity to give visibility to the struggles in my country.

‘Die Remise,’ installation view (detail), Nürtingen Grundschule, Berlin, 2019 // Photo by Maja Wirkus

Exhibition Info

EXROTAPRINT

Berlin Biennale Housewarming

Group Show: ‘exp. 1: The Bones of the World’

Exhibition: Sept. 07 – Nov. 09, 2019

Opening: Friday, Sept. 06, 2019; 5-9pm

Bornemannstraße 9, 13357 Berlin, click here for map