Article by Penny Rafferty in Berlin // Monday, Jan. 08, 2018

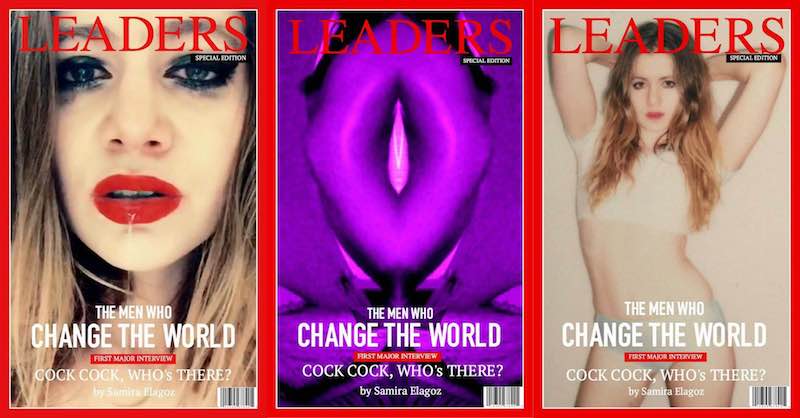

2017 was the year that the truth about sexual misconduct within the cultural sphere broke the headlines—and not just with high profile individual cases like Harvey Weinstein and Artforum’s Knight Landesman being unmasked as long-time sexual predators. Thousands of people’s feeds also held hashtags like #metoo and #notsurprised in response to the global outing of rape culture as an undeniable societal plague. The internet became once again a place for radical trans-local gossip (and I mean that in the best way possible). One artist, however, was ahead of the game: Samira Elagoz.

Elagoz has been using the digital sphere to explore the effects of rape culture since 2015. Having graduated from Amsterdam’s School for New Dance Development, her work offers a unique brand of docu-fiction that explores love, gender, and abuse in today’s digital age. Elagoz’s working practice began after she became a victim of the sexual abuse many people take as a given behind the art world’s doors. Using herself and her lived experiences on websites and apps like Craigslist and Tinder, she addresses the subject of truth through the scope of gender and power, creating unique monologues aided by real-life video and photographic footage. Her work is both unnerving and carefully cute, yet Elagoz is anything but a preacher, and nor is she a victim. Perhaps it’s safest to say she plays the devil’s advocate to her abuse.

Penny Rafferty: I saw your performance ‘Cock Cock…Who’s there?’ at Les Urbaines Festival in 2015. The more than an hour-long performance still resonates with me. I was left wondering if I had just witnessed a Post-feminist emancipation, or a post-Stockholm Syndrome victim wordlessly noting their pleasurable/painful encounter.

Samira Elagoz: I’ve found the performance opens up many—usually unspoken—questions and attitudes around sexual violence, and discloses a discussion within the audience’s own ethics and prejudices. But frankly, exposing the actions one might take after a rape still seems to be a taboo. There appears to be a lot of prejudiced assumptions and opinions surrounding rape. After my experience, I sorely lacked any stories about the aftermath I could actually identify with, so I wanted to share my own. But to now have other victims tell me they see themselves in my work has been very rewarding. Of course, within the socio-political developments of 2017, the work feels more relevant than ever.

PR: When BAL told me their feature topic was ‘Truth’, your work immediately sprung to mind—not because of any explicit link of you being a truthsayer, but more in relation to the contemporary sexual call-out culture online.

SE: The internet allows us to change common consciousness on a wider, more immediate scale than has ever been possible in the past, and this call-out culture is a prime example of that. It’s impressive and I’m excited to see the changes in discourse that have come of it.

However, I have to say, relating specifically to the hashtag, legions of women announcing it is hardly a sign of progress, right? Are we again just reminding ourselves how pervasive such violence is? Will it do much to change perpetrators’ attitudes? It seems shockingly easy for them to come to terms with their conscience. Not to diminish the movement as it stands, nor the platform people now have for voicing their experience and dismay. I can only hope this hashtag indicates how many perpetrators must be in a state of denial about their actions, and might encourage some to review what they had dismissed as actually being violent.

PR: I heard that many victims found viral campaigns like #metoo incredibly difficult, as they would be going about their daily lives and suddenly be reminded of the rape again and again. Your work, however, is all about revisiting the act. It sounds odd to say, but using your words, are you still ‘celebrating’ your ‘rape anniversary’ each year?

SE: ‘Cock Cock.. Who’s There?’ started very simply. It was a year since the rape and I didn’t want it to be this sad event, so I jokingly thought of it as an anniversary celebration. To some, it can sound dark and cynical, but for me, humour is a way to deal with things. I found humour could transform a disempowered perception and gave me a sense of control and agency. But I did not expect to be touring with the performance for two years, so in that sense noting the anniversary does continue, almost monthly.

PR: Agency is a powerful term, as far as being able to tell a story. I remember this quote from your website: “I aim to view my life as cinematic, as material to be manipulated, to see reality as both subjective and malleable.” Where does this stand in terms of truth?

SE: When the material is placed on an editing table it already starts to lose its truthfulness. At the editing table the true story becomes something I can mould, and I think that was one of the more important parts for me, or perhaps one of the most relieving parts. Throughout the process of creating this performance, I found myself in this triangle of equally important pursuits: trying to find the right balance between the personal, the artistic, and the anthropological observations I wanted to share with the work. This process made me view myself and my experiences from so many different sides, especially when contemplating how it might be interpreted by others. Of course, after touring the performance around the world, meeting so many people, hearing or reading the affects my work have had on them…it transformed the rape, perhaps not the memory of it, but most certainly its significance to my life. So one could say through cinematic means life can be edited into a new reality.

PR: Acting in your own life’s script must be hard, at least when deciding what to edit out and keep in.

SE: As soon as I started collecting material, the camera became my partner in crime. I even used it as a confessional or journal in certain moments. But as an artist, you still make work for the stage, no matter how personal it is, and it will, in essence, be viewed by others. It can easily become a masochistic exercise where someone publicly labels themselves as the victim, which in turn becomes their sole identity in the audience’s eyes. Whilst making this performance, one of my main questions was how to unburden the audience of the discomfort of seeing me as a victim, in favour of promoting a frank discussion about the actual topic. I did not want to be the subject, but rather to expose certain patterns and a culture of rape.

PR: But am I right in thinking you never named names?

SE: I was still at university when I made this work and I was told it would be illegal to name someone who had not been convicted of a crime. But more than that, it didn’t feel necessary to me. The work is more about my own process than a platform to accuse. Of course, now many people are naming their attackers, but when I made the work two years ago, call-out culture was not really a thing and victim-blaming was far more prevalent.

PR: Do you think the digital has more potential to perform truth than real life?

SE: My perception leans more towards the film than the digital. But I have, indeed, found that film has the ability to show genuine stages of my life. Rather than it being a mere reenactment or dramatisation, film grants the ability to show progression and change, especially when combined with my stage presence. The audience sees two documentaries: the one on film, where my past self might be emotive or confused; and the one on stage, where my present self is gifted with hindsight and informed by contemplation. I’ve also been very curious as to how people perform themselves, whether that is online or in front of a camera. So when it comes to filming my subjects, I think those reactions, no matter how subtle, are way more telling and informative about gender relations than asking actors to portray them. I show the audience real people in search of attention, validation or some form of intimacy—not a caricature.